An Occult Physiology

GA 128

23 March 1911, Prague

4. Man's inner Cosmic System

Our discussion of yesterday, dealing primarily with the significance of one of those organs which represent an “inner cosmic system” of man, will be continued to-day. We shall then find the transition leading to a description of the functions of the other human organs and organic systems.

It was said to me yesterday in connection with my reference to the spleen that there might arise an apparent contradiction as regards the very important function ascribed to the spleen in the entire being of man; that this contradiction might well appear as a result of the reflection that it is possible to take the spleen out of the body, actually to remove it, and yet not leave the man incapable of living.

Such an objection is certainly justified from the standpoint of our contemporaries; indeed, it is unavoidable in view of the fact that certain difficulties present themselves even to those who approach the spiritual-scientific world-conception as thoroughly honest seekers. It was possible to point out only in a general way in our first public lecture1How May Theosophy be Refuted? delivered 19th March, 1911. Not published in English. how our contemporaries, especially when conscientiously schooled in scientific methods, find difficulties as soon as they choose the road that leads them to an understanding of what may be presented out of the occult depths of cosmic Being.

Now, we shall see in the course of these lectures how, in principle, so to speak, such an objection gradually disappears of itself. I shall, however, to-day call your attention in a prefatory way to the fact that the removal of the spleen from the human organism is thoroughly compatible with everything discussed yesterday. If we really wish to ascend to the truths of spiritual science, we must accustom ourselves gradually to the fact that what we call the human organism, as seen by means of our external senses, and also everything we see in this organism as substance, or it might, perhaps, be better to say as external matter, that all this is not the whole man; but that, underlying man as a physical organism (as we shall explain further) are higher, super-sensible human organisms called the ether-body or life-body, the astral body and the ego; and that we have in this physical organism only the external physical expression for the corresponding formation and processes of the ether-body, the astral body, etc.

When we refer to an organ such as the spleen we think of it in the spiritual-scientific sense, realising that not only does something take place in the external, physical spleen, but that this is merely the physical expression for corresponding processes which take place in the ether-body, for example, or in the astral body. We might say moreover, that the more any one of the organs is the direct expression of the spiritual, the less is the physical form of the organ, that is, what we have before us as physical substance, the determining factor. Just as we find in looking at a pendulum that its movement is merely the physical expression of gravitation, even so is the physical organ merely the physical expression of the super-sensible influences working in force and form—with this difference, however, that in the case of such forces as that of gravitation when we remove the pendulum, which is the physical expression, no inner rhythm due to gravitation can continue. This is the case, of course, in inanimate, inorganic Nature; but not in the same way in animate, organic Nature. When there are no other causes present in the organism as a whole it is not necessary that the spiritual influences should cease with the removal of the physical organ; for this physical organ, in its physical nature, is only a feeble expression of the nature of the corresponding spiritual activities. On this point we shall have more to say later.

Accordingly when we observe the human being, with reference to his spleen, we have to do in the first place, with that organ only; but beyond that with a system of forces working in it which have in the physical spleen only their outward expression. If one removes the spleen, these forces which are integral parts of the organism still continue their work. Their activities do not cease in the way in which, let us say, certain spiritual activities in the human being cease when one removes the brain or a portion of it. It may even be, under certain circumstances, that an organ which has become diseased may cause a much greater hindrance to the continuation of the spiritual activities than is brought about by the removal of the organ concerned. This is true, for example, in the case of a serious disease of the spleen. If it is possible to remove the organ when it becomes seriously diseased, this removal is, under certain conditions, less hindering to the development of the spiritual activities than is the organ itself, which is inwardly diseased and therefore a constant mischief-maker, opposing the development of the underlying spiritual forces.

Such an objection a man may make if he has not yet penetrated very deeply into the real nature of spiritual-scientific knowledge. Though readily understood, this is one of those objections that disappear of themselves when one has time and patience to go more deeply into these matters. You will generally find the following to be true: When anyone approaches what is given out through spiritual science with a certain sort of knowledge gathered from all that belongs to present-day science, contradiction after contradiction may result till finally one can get no further. And, if a man is quick to form opinions, he will certainly not be able to reach any other conclusion than that spiritual science is a sort of madness which does not harmonise in the slightest degree with the results obtained by external science. If, however, a man follows these things with patience, he will see that there is no contradiction, not even of the most minute kind, between what comes forth from spiritual science and what may be presented by external science. The difficulty before us is this, that the field of anthroposophical or spiritual science as a whole is so extensive that it is never possible to present more than a part of it. When people approach such parts they may feel discrepancies such as that which we have described; yet it would be impossible to begin in any other way than this with the much needed bringing of the anthroposophical world-conception into the culture and knowledge of our day.

Yesterday I endeavoured to explain the transformation of rhythm, in the sense I explained, which is undertaken by the spleen in contrast to the rhythmless manner in which human beings take their external nourishment. I took what was said in this connection as my point of departure because it is in itself fundamentally the most easily understood of all the functions belonging to the spleen. We must know, however, that although it is the easiest to understand it is not the most important, it does not constitute the chief thing. For, if it were, people could always say: “Very well, then; if the human being were to take pains to know the right rhythm for his nourishment, the activity of the spleen viewed from this aspect would little by little become unnecessary. From this we see at once that what was described yesterday is the merest trifle. Far more important is the fact that in the process of nourishment we have to do with external substances, external articles of food, their composition and the form and manner in which they exist in our environment. So long as one holds to the conception that these nutritive substances are so much dead bulk, or at best masses containing that sort of life which one generally assumes to be in plants and other articles of food, it may certainly appear as if all that is necessary is for the external substances taken into the organism as nutritive matter to be simply worked over by means of what we call the process of digestion in its broadest sense.

Many people, it is true, imagine that they have to do with some sort of indeterminate substance taken in as food, a substance quite neutral in its relation to us which simply waits, when we have once taken it in, till we are able to digest it. But such is not the case. Articles of food are, after all not just bricks which serve in some sort of way as building material for the construction they are to help in erecting. Bricks are included in the architect's plan in any way he pleases to use them because they represent in relationship to the building a mass in itself quite inert. This is not true, however, of nutritive matter in its relation to the human being. For every particle of substance we have in our environment has certain inner forces, its own conformity to law. This is the essential element in any substance that it has its own inner laws, its own inner activities. Accordingly, when we bring external nutritive substances into our organism, when we insert them into our own inner activity, so to speak, they do not simply consent to this at once as a matter of course but attempt first to develop their own laws, their own rhythms and their own inner forms of movement.

Thus, if the human organism wishes to use these substances for its own purposes it must first destroy their rhythmic life, as it were, that vital activity which is peculiarly their own. It must do away with these, not merely working over some indifferent material, but working in opposition to certain laws characteristic of these substances. That these substances do have their own laws can soon be felt by the human being when, for instance, a strong poison is conveyed through the digestive canal. He soon feels, in such a case, that the particular law belonging to this substance has mastered him, that these laws now assert themselves. Just as every poison has in general its own inner laws by means of which it carries out an attack on our organism, so it is with every substance, with all the nutriment that we take in. It is not something neutral, but rather it asserts itself in accordance with its own nature, its own quality of being. It has, we may say, its own rhythm. This rhythm must be combated by the human being, so that it is not only a case of working over neutral building material within man's inner organisation, but rather that the peculiar nature of this building material must first be mastered.

We may say, therefore, that in those organs which our food first encounters inside the human being we have the instruments with which to oppose in the first place, what constitutes the peculiar life of the nutritive substance “life” here to be conceived in its wider meaning, so that even the apparently lifeless world of nature, with its laws of movement, is included. That which the food has within it as its own rhythm, which contradicts the human rhythm, must be modified. And in this work of change the organism of the spleen is, so to speak, the outpost. In this changing of the rhythm, however, in this work of re-forming and of defending, the other organs we have mentioned also participate; so that in the spleen, the gall-bladder, and the liver we have a co-operating system of organs whose main function it is, when food is received into the organism, to repel what constitutes the particular inner nature of this food. All the activity first developed in the stomach, or even before the food reaches it, and everything which is then brought about by the secretions2For a fuller explanation of the terms translated in these Lectures as secretion and excretion. see note on p. 79. of the gall, and which takes place further through the activity of the liver and the spleen, all of this results in that warding off we have mentioned of the peculiar nature of the nutritive substances.

Thus our food is adapted, we may say, to the inner rhythm of the human organism only when it has been met by the counter-activity of these organs. Only, therefore, when we have taken in our nutriment, and have exposed it to the activity of these organs, do we have in us something capable of being received into that organic system which is the bearer, the instrument, of our ego. Before any sort of external nutritive substance can be received into this blood of ours, so that the blood shall become capable of serving as the instrument of our ego, all those forms of law peculiar to the external world must be set aside, and the blood must receive the nutriment in such form as corresponds to the particular nature of the human organism. We may say, therefore, that in the spleen, the liver and the gall-bladder as they are in themselves and as they react upon the stomach, we have those organs which adapt the laws of the outside world, from which we take our food, to the inner organisation, the inner rhythm, of man.

This human nature, however, in all its working as a totality and with all its members, confronts not only the inner world; it must also be in a continual correspondence or intercourse with the outside world, in a continual living reciprocal activity in relation to that world. This living interaction with the world outside is cut off by the fact that, in so far as we come into connection with it through our nutritive material, the three organ-systems of the liver, the gall-bladder, and the spleen are placed in opposition to the laws of that world. From this side, through these organs, conformity to external law is eliminated. If the human organism were exposed only to these systems of organs it would shut itself off completely, so to speak, from the outside world, would itself become, as a system of organs, an entity completely isolated in itself. Something else, therefore, is necessary. Just as the human being needs, on the one hand, organ-systems by means of which the outside world is so reshaped as to be in accordance with his inner world, so must he be in a position also, on the other hand, to confront the outside world directly with the help of the instrument of his ego: that is, he must place his organism, which otherwise would remain a kind of entity isolated within itself, in direct continual connection with the outside world.

Whereas the blood enters into connection with the external world from the one direction, only in such a way that it contains that part of this world alone from which all forms of law peculiar to it have been cast aside, from the other side it enters into relation with this external world so that it can in a certain sense come into direct contact with it. This happens when the blood flows through the lungs and comes into contact with the outer air. It is there renewed by means of the oxygen in this outer air, and is brought into such a form that nothing can now weaken it in this form; so that the oxygen of the air thus actually meets the instrument of the human ego in a condition that conforms with its own essential nature and quality of being.

There appears thus before our eyes this truly remarkable fact: that what we may call the noblest instrument possessed by man, his blood, which is the instrument of his ego, stands there as an entity that receives all its nourishment, everything that it takes from the life of the outside world, carefully filtered by the organ-systems we have characterised. In this way the blood is made capable of becoming a complete expression of the inner organisation of man, the inner rhythm of man. On the other hand, however, in so far as the blood comes into direct contact with the outside world, with that particular substance in the external world that may be taken in as it is, in its own inner form of law, its own vital activity, without needing to be directly combated, to that extent is this human organism not something secluded within itself but at the same time in full contact with the world outside.

We have, accordingly, in this blood-organism of man, looked at from this standpoint, something very wonderful. We have in it an actual, genuine means of expression of the human ego, which is in fact turned toward the external world on the one side, and on the other toward its own inner life. Just as man is directed through his nerve-system, as we have seen, toward the impressions of this outer world, taking the outer world into himself; as it were, through the nerves by way of the soul, just so does he come into direct contact with the outer world through the instrument of his blood, in that the blood receives oxygen from the air through the lungs. We may say, therefore, that in the system of the spleen, liver, and gall-bladder, on the one hand, and in the lung-system on the other, we have two systems which counteract each other. Outer world and inner world, so to speak, have an absolutely direct contact with each other in the human organism by means of the blood, because the blood comes into contact on the one side with the outer air and on the other with the nutritive material that has been deprived of its own nature. One might say that the action of two worlds comes into collision within man, like positive and negative electricity. We can very easily picture to ourselves where that organ-system is located which is designed to permit the mutual rebounding of these two systems of cosmic forces to act upon it. Upward as far as the heart there work the transformed nutritive juices, inasmuch as the blood, which carries them, streams through the heart; inward to the heart, inasmuch as the blood flows through it, works the oxygen of the air which enters the blood directly from the outer world. We have in the heart, therefore, that organ in which there meet each other these two systems into which the human being is interwoven and to which he is attached from two different directions. The whole inner organism of man is joined to the heart on the one side, and on the other, this inner organism itself is connected directly through the heart with the rhythm, the inner vital activity, of the outer world.

It is quite possible that when two such systems collide the direct result of their interaction may be a harmony. The system of the great outside world or macrocosm presses upon us through the fact that it sends the oxygen or the air in general into our inner organism, and the system of our small inner world or microcosm transforms our nourishment; therefore we might imagine that these systems, because of the fact that the blood streams through the heart, are able in the blood to create a harmonious balance. If this were so, the human being would be yoked to two worlds, so to speak, providing him with his inner equilibrium. Now, we shall see later in the course of these lectures, that the connection between the world and the human being is not such that the world leaves us quite passive—that it sends its forces into us in two different ways, while we are simply harnessed to their counteracting influences. No, it is not like that; but rather, as we shall more and more learn to know, the essential thing with regard to man is the fact that at last a residue always remains for his own inner activity; and that it is left ultimately to man himself to bring about the balance, the inner equilibrium, right into his very organs. We must, therefore, seek within the human organism itself for the balancing of these two world-systems, the harmonising of these two systems of organs. We must realise that the harmonising of these two organ-systems is not already provided through that kind of conformity to law operating outside man and that other kind of conformity to law which works only within his own organism, but that this must be evoked through the help of an organ-system of his own. Man must establish the harmony within himself. (We are not now speaking of the consciousness, but of those processes which take place entirely unconsciously within the organ-systems of the human being.) This balancing of the two systems, the system of spleen, liver, gall-bladder on the one hand and the lung-system on the other, as they confront the blood which flows through the heart is, indeed, brought about. It is brought about through the fact that we have the kidney-system inserted in the entire human organism and in intimate relationship with the circulation of the blood.

In this kidney-system we have that which harmonises, as it were, the outer activities due to the direct contact of the blood with the air and those other activities proceeding from the inner human organism itself in that the food must first be prepared by being deprived of its own nature. In this kidney-system, accordingly, we have a balancing system between the two kinds of organ-systems previously characterised; and the organism is in a position by means of this system to dispose of the excess which otherwise would result from the inharmonious interaction of the two other systems.

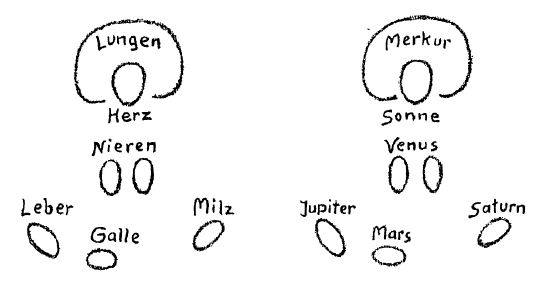

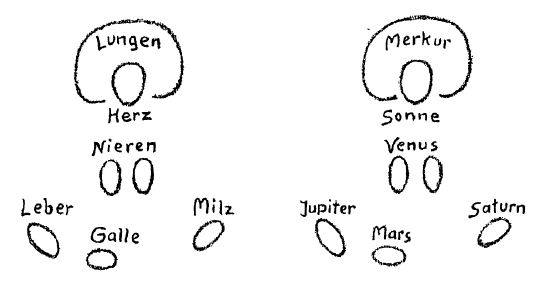

Over against the entire inner organisation, the organs belonging to the digestive apparatus (in which we must include the organs we have learned to know as liver, gall-bladder, and spleen), we have placed that system for which these organs primarily develop their preparatory activity, namely, the blood-system. But also over against this blood-system we have placed those organs which work, on the one hand to counteract a one-sided isolation, but on the other hand to create a balance between the inner systems we have mentioned and what presses inward from without. If we think, therefore, of the blood-system with its central point, the heart, as placed in the middle of the organism—and we shall see how truly justifiable this is—we have adjoining this system of blood and heart, on the one side the spleen, liver, and gall-bladder systems, and connected with it on the other side the lung and kidney systems. We shall emphasise later on how extremely close this connection is between the lung-system and the kidney-system. If we sketch the systems side by side we have in them everything belonging to the inner organisation of man which is related in a special way, and which so presents itself to us in this relationship that we are obliged to look upon the heart, together with the blood-system belonging to it, as by far the most important part. Now, I have already pointed out, and we shall see even more definitely to what an extent such a giving of names as we have described is justified, that in occultism the activity of the spleen is characterised as a Saturn-activity, that of the liver as a Jupiter-activity, and that of the gall-bladder as a Mars-activity. On the same basis on which these names were chosen for the activities here referred to, occult knowledge sees in the heart and the blood-system belonging to it something in the human organism which merits the name Sun, just as the sun outside merits this name in the planetary system. In the lung-system, there is contained what the occultists, according to the same principle, characterise as Mercury, and in the kidney-system that which merits the name Venus. Thus, by means of these names, we have pointed out in these systems of the human organism, even if at the present moment we do not in the least undertake a justification of the names, something like an inner world system. We have, moreover, supplemented this inner world system in that we have placed ourselves in a position to observe the relationship which manifests itself in the very nature of man as holding good for the two other organ-systems having a certain special connection with the blood-system. Only when we observe these things in such a way do we present something complete in respect to what we may call the real inner human world. In the following lectures I shall have occasion to show you that the occultists have actual reasons for conceiving the relationship of the sun to Mercury and Venus as being similar to that which we must necessarily think of as existing between the heart and lungs and kidneys respectively, within the human organism.

We see, therefore, that in the instrument of our ego, our blood-system, expressing its rhythm in the heart, something is present that is determined to a certain extent in its entire formation, its inner nature and quality of being, by man's inner world system; something that must first be embedded in the inner world system of the human being before it can live as it actually does live. We have in this human blood-system, as I have often stated, the physical instrument of our ego. Indeed, we know that our ego as constituted is only possible by reason of the fact that it is built up on the foundation of a physical body, an ether-body, and an astral body. An ego free to fly about in the world by itself, as a human ego, is unthinkable. A human ego within this world, which is the world that for the moment concerns us, presupposes as its basis an astral body, an ether-body, and a physical body.

Now, just as this ego in its spiritual connection pre-supposes the three members of man's being we have just named, so does its physical organ, the blood-system, which is the instrument of the ego, presuppose likewise on the physical side corresponding images, as it were, of the astral body and the ether-body. Thus the blood-system can carry out its evolution only on the basis of something else. Whereas the plant simply evolves out of inanimate and inorganic nature, in that it grows directly out of this, we must say that in the case of the human blood-organism the mere outer world cannot serve as a basis in the way that it serves the plant, but this outer world must first be transformed by way of our nutrition. And just as the physical body of man must bear within itself the ether-body and the astral body, so what streams in with the food must first be transformed before that which is the instrument of the human ego can merge itself with these transformed nutritive substances.

Even though we may say that the nature of this physical organ, this physical instrument of the human ego, is determined in the lung-system by the outer world, it is nevertheless so determined by the outer world that it is, after all, an organ of the human bodily organisation. Here again we must differentiate between what comes to man from outside in the form of air (is breathed in and enables him to permeate his blood directly with the rhythm belonging to the outer world) and what approaches the blood, the living instrument of the ego in the organism, not directly, but, as has already been described, by the roundabout path of the soul: everything, namely, that man takes in by receiving the impressions of the outer world through the senses, so that the senses then convey these impressions to the tablet of the blood.

We may, therefore, state it thus: Not only does man come by means of the air into direct physical contact with the outside world, in that this contact works right into his blood; but by means of the sense organs he also comes into contact with the outside world in such a way that this contact is a non-physical one, taking place through the process of perception which the soul unfolds when it comes into relation with its environment.

We here have something like a higher process in addition to the process of breathing, something like a spiritualised breathing process. Whereas through the breathing process we take the outer world in the form of matter into our organism, we take, through the process of perception, by which I mean here everything that we work over inwardly in connection with the external impressions we receive, something into our organism which is a spiritualised process of breathing. And there now arises the question: “How do these two processes work together?” For in the human organism everything must have a reciprocal, a counterbalancing activity. Let us for a moment put this question still more exactly, for certain essential things will depend upon an accurate presentation.

In order to be able to convey to our minds the answer which we shall give to-day hypothetically, we must first understand clearly how an interaction, a reciprocal activity, can take place between all that works through the blood, all that the blood has changed into through the fact that the different processes have come about under the influence of the inner world system, and what we carry on as processes of external perception. For, in spite of the fact that the blood is thus filtered, and even though so much care has been taken to make it the wonderfully organised substance it is, so that it can be the instrument of our ego, in spite of this it is nevertheless primarily a physical substance in the human organism, and belongs as such to the physical body. At first, therefore, there seems to be a very great difference between this human blood, which has been prepared as it has, and what we know as our processes of perception, everything, that is, which the soul performs. Indeed, this is an undeniable reality, for anyone would have to be remarkably lacking in ability to think, who would deny that perceptions, concepts, feelings, and will-impulses exist just the same as does a blood-substance, a nerve-substance, a liver-substance, a gall-substance. As to how these things are connected world-conceptions might begin to conflict. They might dispute, let us say, as to whether thoughts are merely some sort of activity of the nerve-substance, or something of that sort. It is only at this point that the conflict can begin between the different world-conceptions. No world-conception can dispute over the obvious fact that our inner soul-life, our thought-life, our feeling-life, everything which builds itself up on the foundation of external perceptions and impressions, presents a reality in itself. Note well that I did not say, in the first place, “an absolutely isolated reality,” but “a reality in itself,” for nothing in the world is isolated. The words “reality in itself” are intended to indicate what may be observed as being real within our inner world system; and to this last belong all our thoughts, feelings and so forth, quite as truly as do the stomach, the liver, and the gall-bladder.

Yet something else may strike us when we see these two realities side by side—everything on the one hand which, even though so thoroughly filtered, is none the less physical, namely, the blood; and on the other hand that which at first appears, indeed, to have nothing at all to do with anything physical, namely, the content of the soul-life, consisting of feelings, thoughts and so forth. As a matter of fact this very aspect of these two kinds of reality presents man with such difficulties that the most varied answers, offered by the most diverse world-conceptions, have come to be associated with it.

There are world-conceptions, for instance, that believe in a direct influence upon physical substance of everything connected with the soul, with thought and with feeling, as if thought could work directly upon physical substance. In contrast to these, there are others which assume that thoughts, feelings, and so forth, are simply the products of the processes that take place in physical substance. The dispute between these two world-conceptions has through long periods of time played an important role in the outside world, but not in the field of occultism, in which it is considered a dispute over empty words.

Since no ultimate agreement was reached, there has appeared during more recent times still another conception bearing the strange name of “psychologic-physical parallelism.” If I were to express it rather trivially I might say that since the disputants had no longer any other resource, not knowing whether spirit works upon the processes of the physical body or whether these bodily processes influence the spirit, they concluded that there are two processes running parallel courses. They argued: at the same time that man thinks, feels and so forth, certain definite parallel processes are taking place in his physical organism. The perception, “I see red,” would according to this correspond to some sort of material process. But they do not go any further than to say that it “corresponds.” Indeed, this is a mere expedient which leads them out of all their difficulties, but only in the sense that it sets these aside, not that it overcomes them. All the disputes that have arisen on this basis, including the futility of the psychologic-physical parallelism, result from the fact that people insist upon deciding these questions on a basis upon which they simply cannot be decided. We have to do with non-material processes when we consider the activities of our soul-life as inner life; and we have to do with material processes when we centre our attention upon the blood, the most highly organised thing in us. If we simply compare these two things, physical activities and soul-activities, and then seek by means of reflection to find out how each of them works upon the other, we shall not arrive anywhere. Through reflection one may find all sorts of arbitrary solutions or non-solutions. The only way to determine anything in regard to these questions is actually to establish a higher knowledge. This does not limit itself either to viewing the outer world with the physical senses or to thought that is bound up with a merely physical external world, but elevates itself to a certain extent to what leads beyond the physical, and likewise to that which leads into the super-physical world from our own inner soul-life which indeed we experience in the physical world. We must ascend, on the one hand, from the material to the super-sensible, the super-material. On the other hand, we must ascend also from our soul-life to the super-physical, that is, to that which lies at the basis of our soul-life in the superphysical world; for our soul-life, with all its feelings, etc., is, of course, something that we experience in the physical world. We must, accordingly, ascend from both sides to a super-physical world.

Now, in order to ascend from the material side to the super-physical world, those soul-exercises are necessary which enable man to look behind the external, the sensible, behind that veil, of which I spoke yesterday, into which are woven our sense-impressions. Moreover, such sense-impressions as these we also have before us, of course, when we observe the whole external organism of man. And when we descend to the very finest element of the human organism, to the blood, we are, nevertheless, dealing with a merely physical-sensible thing when we observe it, at first, with the physical senses, or at least with the instruments and methods of external science, which give us just such a picture of the blood as would an external eye if it could see this blood directly.

We have said, then, that with the help of such soul-exercises as lead up into the super-sensible world, we can penetrate into the foundations of the physical world, into the super-sensible element in the human organism. In doing this, the first super-sensible thing we meet in this human organism is what we call the ether-body. This ether-body (and we shall describe it still more accurately from the standpoint of occult physiology) is a super-sensible organisation, which we first think of simply as the super-sensible basic substance out of which the sensible or physical organism of man is constructed, and of which it is a copy. Of course the blood is also an impress or copy of this ether-body. Thus we have already at this point, by coming only one stage beyond the sense-organism, something super-sensible in the human ether-body, and the question now arises: are we able to approach this super-sensible also from the other side, from the side of the soul-life, from what we experience in the sensations, thoughts and feelings that we build up on the basis of our impressions of the outside world?

We have already seen that we cannot approach the physical organism directly, for the physical and material place themselves in our way. Can we approach the ether-organism? It is clear that we cannot approach it as directly as we can our soul-life. When we are at work in our soul what at first happens is that we receive external impressions. The outside world acts upon our senses, and we then work over the external impressions in our soul. But we do more than that, we store up, so to speak, these impressions which we have received. Just think for a moment about the simple phenomenon of memory, when you recall something that you experienced, perhaps years ago. At that time, on the basis of external perceptions, certain impressions took form, which you then worked over, and which you draw up to-day out of the depths of your soul, and to-day there comes to you the memory, it may be something quite simple: the memory of a tree, let us say, or an odour. Here you have stored up something in your soul which could remain yours from the external impression and the elaboration of it in your soul, something that can form in you the recollection.

We now find, however, through observation of the soul-life attained through exercises of the soul, that in the moment when we have developed our soul-life far enough to be able to store up mental pictures in the memory we are not working with our soul experiences only in our ego. We first confront the outside world with our ego, take impressions from it into our ego, and work these over in our astral body. But, were we to work them over only in the astral body, we should straightway forget them. When we draw conclusions we are at work in our astral bodies; but when we fix impressions within us so firmly that, after some little time has passed, or indeed after only a few minutes, we can again recall them, we have stamped upon our ether-body these impressions received through our ego and worked over in our astral body. In these memory-pictures, accordingly, we have drawn out of our ego down into our ether-body that which we have lived over inwardly as activity of soul in our contact with the outer world. Now, if we have something which impresses upon the ether-body our memory-pictures taken, as it were, from the soul, and if from the other side we recognise the ether-body as that super-sensible expression of our organism which is nearest to the physical, the question then arises: How does this impressing come about? In other words, when the human being works over external impressions, makes them into memory-pictures, and in doing so thrusts them into his ether-body, how does it happen that he does actually bring down into the ether-body what the astral body has first worked over and what now presses against the ether-body? How does he transfer it?

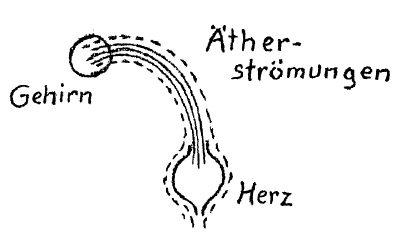

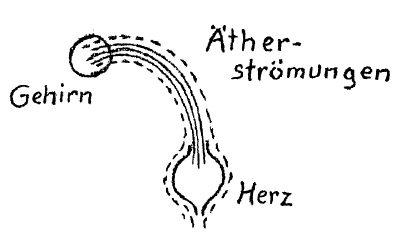

This transfer takes place in a very remarkable way. If we observe the blood—let us now imagine ourselves within the human ether-body—quite schematically as it courses through the heart, and think of it as the external physical expression of the human ego, we thereby see how this ego works, how it receives impressions corresponding with the outer world and condenses these to memory-pictures. We see, furthermore, not only that our blood is active in this process, but also that, throughout its course, especially in the upward direction, somewhat less in the downward, it stirs up the ether-body, so that we see currents developing everywhere in the ether-body, taking a very definite course, as if they would join the blood flowing upward from the heart and go up to the head. And in the head these currents come together, in about the same way, to use a comparison belonging to the external world, as do currents of electricity when they rush toward a point which is opposed by another point, so as to neutralise the positive and the negative. When we observe with a soul trained in occult methods, we see at this point ether-forces compressed as if under a very powerful tension, those ether-forces which are called forth through the impressions that now desire to become definite concepts, memory-pictures, and to stamp themselves upon the ether-body.

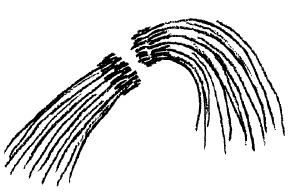

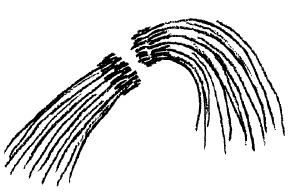

I shall, therefore, draw here the last out-streamings of these ether-currents, as they flow up toward, the brain, and show their crowding together somewhat as this would actually appear. We see here a very powerful tension which concentrates at one point, and announces: “I will now enter into the ether-body!” just as when positive and negative electricity are impelled to neutralise each other. We then see how, in opposition to these, other currents flow from that portion of the ether-body which belongs to the rest of the bodily organisation. These currents go out for the most part from the lower part of the breast, but also from the lymph vessels and other organs, and come together in such a way that they oppose these other currents. Thus we have in the brain, whenever a memory-picture wishes to form itself, two ether-currents, one coming from below and one from above, which oppose each other under the greatest possible tension, just as two electric currents oppose each other. If a balance is brought about between these two currents, then a concept has become a memory-picture and has incorporated itself in the ether-body.

Such super-sensible currents in the human organism always express themselves by creating for themselves also a physical sense-organ, which we must first look upon as a sense-manifestation. Thus we have within us an organ, situated in the centre of the brain, which is the physical sense-expression for that which wishes to take the form of a memory-picture; and opposite to this is situated still another organ in the brain. These two organs in the human brain are the physical-sensible expression of the two currents in the human ether-body; they are, one might say, something like the ultimate indication of the fact that there are such currents in the ether-body. These currents condense themselves with such force that they seize the human bodily substance and consolidate it into these organs. We thus actually get an impression of bright etheric light-currents streaming across from the one to the other of these organs, and pouring themselves out over the human ether-body. These organs are actually present in the human organism. One of them is the pineal gland; the other, the so-called pituitary body: the “epiphysis” and the “hypophysis” respectively. We have here, at a definite point in the human physical organism, the external physical expression of the co-operation of soul and body!

This is what I wished in the first place to give you by way of general principles. With this we conclude to-day's lecture, and tomorrow we will continue our discussion further and find yet more to add to it. It is always important to hold firmly and clearly to the thought that we can always investigate the super-sensible, and can ask ourselves whether the physical expression of the super-sensible world that we should expect to find is actually present. We see. here that these sense-expressions of the super-sensible actually do exist. Since we have here, however, a question of an entrance gate from the sense-world to the super-sensible, you will understand that these two organs are in the highest degree puzzling to physical science, and you will, therefore, be able to get from external science only inadequate information with regard to them.

Vierter Vortrag

Die gestrige Auseinandersetzung über die Bedeutung zunächst eines derjenigen Organe, welche gleichsam ein inneres Weltsystem des Menschen darstellen, soll heute fortgesetzt werden. Dann soll der Übergang gefunden werden zur Beschreibung der Aufgaben anderer Organe und Organsysteme des Menschen.

Es ist mir gestern in Anknüpfung an das, was hier über das Organ der Milz vorgetragen wurde, gesagt worden, daß sich doch ein scheinbarer Widerspruch ergeben könnte gegenüber jener wichtigen Aufgabe, die dem Organ der Milz im Gesamtwesen des Menschen gestern zugeschrieben worden ist. Dieser Widerspruch könnte sich ergeben, wenn man bedenkt, daß es ja möglich ist, die Milz aus dem Körper herauszunehmen, sie also aus dem Körper zu entfernen, ohne durch diese Entfernung der Milz den Menschen lebensunfähig zu machen.

Ein solcher Einwand ist natürlich einer derjenigen, die von unserem gegenwärtigen zeitgenössischen Standpunkte aus voll berechtigt sind und die gerade denjenigen gewisse Schwierigkeiten bieten, welche in ganz ehrlich suchender Art an die geisteswissenschaftliche Weltanschauung herankommen. Nur im allgemeinen konnte ja in dem ersten öffentlichen Vortrage darauf hingewiesen werden, wie unsere heutigen Zeitgenossen — namentlich dann, wenn sie ein durch die wissenschaftlichen Methoden geschultes Gewissen haben Schwierigkeiten zu überwinden haben, wenn sie sich auf den Weg begeben, dasjenige zu verstehen, was aus den okkulten Untergründen des Weltwesens dargestellt wird. Nun werden wir ja im Laufe der Vorträge im Prinzip von selber sehen, wie sich ein solcher Einwand beheben läßt. Ich will aber doch heute schon vorbemerkend darauf aufmerksam machen, daß die Entfernung der Milz aus dem menschlichen Organismus durchaus vereinbar ist mit dem, was gestern auseinandergesetzt worden ist. Wenn Sie wirklich aufsteigen wollen zu den geisteswissenschaftlichen Wahrheiten, müssen Sie sich ja allmählich dareinfinden, daß dasjenige, was wir den menschlichen Organismus nennen, was wir durch unsere äußeren Sinne wahrnehmen, was wir substantiell, materiell an diesem menschlichen Organismus sehen, daß dies nicht der ganze Mensch ist, sondern daß dem physischen Organismus — das werden wir noch weiter auszuführen haben — zugrundeliegen höhere, übersinnliche Organisationen: der Ätherleib oder Lebensleib, der astralische Leib und das Ich, und daß wir im physischen Organismus nur den äußeren, den physischen Ausdruck haben für die entsprechende Gestaltung, für die entsprechenden Vorgänge des Ätherleibes, des Astralleibes und des Ich. Wenn wir auf ein solches Organ hinweisen wie die Milz, so meinen wir es im geisteswissenschaftlichen Sinne so, daß im Grunde genommen nicht nur in der äußeren physischen Milz etwas vor sich geht, sondern daß das, was in der physischen Milz vorgeht, nur der physische Ausdruck ist für entsprechende Vorgänge im Ätherleibe oder im Astralleibe. Und man könnte sagen: Je mehr ein Organ der unmittelbare physische Ausdruck eines Geistigen ist, desto weniger ist die physische Form des Organs, also das, was wir physisch-substantiell vor uns haben, das eigentlich Maßgebende. Wenn wir ein Pendel ansehen, so ist die Pendelbewegung nur der physische Ausdruck für die Schwerkraft. Ebenso ist ein physisches Organ nur der physische Ausdruck für übersinnliche Kraft- und Formwirkungen. Nun ist allerdings ein Unterschied zwischen den Folgen der Schwerkraft, welche sich in der Pendelbewegung zeigen, und den Folgen, welche entstehen durch die Wirkungen des Äther- und Astralleibes auf die Milz. Nimmt man das Pendel weg, so ist kein Objekt mehr vorhanden, an welchem sich der durch die Schwerkraft bewirkte Rhythmus zeigen kann. So ist es bei der unbelebten, anorganischen Natur, beim belebten Organismus ist es anders. Wenn nicht Gründe vorliegen, von denen wir noch sprechen werden, so hören mit der Wegnahme des physischen Organs nicht notwendigerweise auch die geistigen Wirkungen der höheren Organisationen auf.

Wenn wir also den Menschen in bezug auf seine Milz ansehen, so haben wir es zunächst zu tun mit der physischen Milz, und dann mit einem System von Kraftwirkungen, die in der Milz nur ihren physischen Ausdruck haben. Wenn man die Milz wegnimmt, dann sind diese Kraftwirkungen, die einmal dem menschlichen Organismus eingegliedert wurden, noch da, sie hören nicht auf. Es kann unter Umständen sogar sein, daß durch die Anwesenheit eines erkrankten physischen Organs ein viel größeres Hindernis eintritt für die Fortdauer der geistigen Wirkungen als durch die Herausnahme des betreffenden Organs. Das kann zum Beispiel bei einer schweren Erkrankung der Milz der Fall sein. Wenn es bei einer schweren Erkrankung eines Organs möglich ist, das Organ zu entfernen, so ist unter Umständen das Fehlen dieses Organs ein geringeres Hindernis für die Entfaltung der geistigen Wirkungen als die Anwesenheit des erkrankten Organs, das ein fortwährender Störenfried ist für die Entwickelung der geistigen Kraftwirkungen. Daher gehört ein solcher Einwand, wie der angeführte, zu denjenigen, welche man gewiß macht, wenn man noch nicht tiefer in das eigentliche Wesen des geisteswissenschaftlichen Erkennens eingedrungen ist. Ein ganz begreiflicher Einwand ist es, aber zu gleicher Zeit einer derjenigen, die ganz von selbst verschwinden, wenn man sich Zeit läßt und Geduld hat, um tiefer in die Sache einzudringen. Diese Erfahrung werden Sie überhaupt machen: Wenn man mit einem gewissen Wissen, das aus den Anschauungen der heutigen materialistischen Wissenschaft geschöpft ist, an das Studium der Geisteswissenschaft herantritt, da kann sich Widerspruch auf Widerspruch ergeben, so daß man gar nicht zurechtkommen kann. Und wenn man da schnell fertig ist mit dem Urteilen, so wird man ja allerdings zu keinem anderen Ergebnis kommen können als zu dem, daß Geisteswissenschaft etwas Hirnverbranntes sei, das nicht im geringsten übereinstimme mit den Ergebnissen der äußeren Wissenschaft. - Wenn man aber sich mit Geduld und Zeit auf die Sache einläßt, dann wird man sehen, daß es keinen Widerspruch, auch nicht geringfügigster Art, gibt zwischen dem, was aus der Geisteswissenschaft kommt, und dem, was sich aus der äußeren wissenschaftlichen Forschung ergibt. Die Schwierigkeit, die da vorliegt, ist die, daß das Gesamtgebiet des anthroposophischen oder geisteswissenschaftlichen Erkennens ein so weites ist, daß man immer nur Teile geben kann. Und wenn die Leute an diese Teile herantreten, können sie leicht solche Widersprüche fühlen wie diesen charakterisierten.

Aber das darf uns nicht zurückschrecken, man würde ja sonst gar nicht anfangen können mit dem notwendigen Hereinbringen anthroposophischer Weltanschauung in die Gesamtbildung und in das Gesamtwissen unserer Zeit.

Gestern versuchte ich Ihnen darzulegen jene Umrhythmisierung, welche durch die Milz bewirkt wird gegenüber dem äußeren rhythmuslosen Ernähren des Menschen. Ich bin davon ausgegangen, weil es von allen Funktionen, welche die Milz hat, die am leichtesten verständliche ist. Aber obzwar es die am leichtesten verständliche ist, ist sie nicht die allerwichtigste und auch nicht die, welche die Hauptsache bildet. Denn man könnte ja sagen: Nun ja, wenn der Mensch sich bemühen würde, den richtigen Rhythmus für seine Ernährung zu erkennen, so würde in dieser Hinsicht die Tätigkeit der Milz nach und nach eine unnötige werden müssen. — Schon daraus ersieht man, daß diese Funktion, von der wir gestern gesprochen haben, die geringfügigste ist. Weit wichtiger ist die Tatsache, daß wir bei unserer Ernährung den Nahrungsmitteln als äußeren Stoffen, in der Art und Weise ihrer Zusammensetzung, wie sie sich in unserer Umgebung vorfinden, gegenüberstehen. Solange man freilich die Anschauung hat, daß diese Nahrungsmittel tote Stoffe seien oder höchstens von dem Leben erfüllt, das man in den Pflanzen voraussetzt, solange man dies annimmt, könnte es allerdings scheinen, als ob der äußere Stoff, der da als Nahrung aufgenommen wird in den Organismus, durch das verarbeitet wird, was man im weitesten Sinne die Verdauung nennt. Gewiß stellen sich ja auch viele Menschen die Sache so vor, daß man es mit einem bestimmungslosen Stoff zu tun hat, den wir als unsere Nahrung aufnehmen, mit einem Stoff, der ganz gleichgültig ist gegen uns selbst und der nur darauf wartet, wenn wir ihn aufgenommen haben, daß wir ihn auch verarbeiten können. So ist es aber nicht. Die Nahrungsstoffe sind doch nicht wie Ziegelsteine, die es sich gefallen lassen müssen, in jeder Art als Bausteine an einem Bau zu dienen, der eben aufgeführt werden soll. Die Ziegelsteine lassen es sich gefallen, in beliebiger Weise nach dem Plan des Architekten einem Bau eingefügt zu werden, weil sie eine in sich ungefügte, leblose Masse darstellen, wenigstens in bezug auf den Bau. So ist es aber nicht bei den Nahrungsmitteln in bezug auf den Menschen. Denn ein jedes Substantielle, das wir in unserer Umgebung haben, hat gewisse innere Kräfte, hat eine innere Gesetzmäßigkeit. Und das ist das Wesentliche eines Stoffes, daß er innere Gesetzmäßigkeiten, innere Regsamkeiten hat. Wenn wir also die äußeren Nahrungsstoffe in unseren Organismus hineinbringen, sie sozusagen unserer eigenen inneren Regsamkeit einfügen wollen, so lassen sie sich das nicht ohne weiteres gefallen, sondern legen es zunächst darauf an, ihre eigenen Gesetze, ihre eigenen Rhythmen und ihre eigenen inneren Bewegungsformen zu behalten. Und will der menschliche Organismus sie für seine Zwecke gebrauchen, so muß er zunächst die eigene Regsamkeit dieser Stoffe vernichten, er muß sie aufheben. Er muß nicht bloß ein gleichgültiges Material verarbeiten, sondern er muß der eigenen Gesetzmäßigkeit der Stoffe entgegenarbeiten. Daß diese Stoffe eine Eigengesetzmäßigkeit haben, das kann der Mensch zum Beispiel bald spüren, wenn er ein starkes Gift zu sich nimmt. Da wird er bald sehen, daß die Eigengesetzmäßigkeit des Giftes sich geltend macht und Herr über ihn wird. So wie aber ein Gift eine innere GesetzmäRigkeit hat, durch die es eine Attacke auf den Organismus ausführt, so ist es mit jedem Nahrungsstoff, den wir zu uns nehmen. Er ist nicht etwas Gleichgültiges, sondern er macht sich in seiner eigenen Natur, in seiner eigenen Wesenheit geltend; er hat seinen eigenen Rhythmus. Und diesem Rhythmus muß vom Menschen entgegengearbeitet werden, so daß nicht nur gleichgültige Baumaterialien zu verarbeiten sind in der inneren Organisation des Menschen, sondern es muß zuerst die eigene Natur dieser Baumaterialien überwunden werden.

So können wir sagen, daß wir in den Organen, denen unsere Nahrungsstoffe im Inneren des Menschen zuerst entgegentreten, die Werkzeuge haben, um demjenigen entgegenzuarbeiten, was Eigenleben der Nahrungsstoffe ist — jetzt «Leben» im weitesten Sinne aufgefaßt. Nicht nur das, was wir durch unregelmäßigen Rhythmus in der Ernährung selber bewirken, sondern auch das, was die Nahrungsstoffe an eigenem Rhythmus in sich haben, welcher dem menschlichen Rhythmus widerspricht, das muß umrhythmisiert werden. Von den Organen, die dies bewirken, ist die Milz das äußerste Organ. Aber an diesem Umrhythmisieren, an diesem Umgestalten und Abwehren arbeiten die anderen genannten Organe wesentlich mit, so daß wir in Milz, Leber und Galle ein zusammenwirkendes Organsystem haben, welches im wesentlichen dazu bestimmt ist, bei der Aufnahme der Nahrungsmittel in den Organismus dasjenige zurückzuschieben, was Eigennatur dieser Nahrungsmittel ist. Alle Tätigkeit, welche im Magen entfaltet wird, oder auch schon, bevor die Speise in den Magen gelangt, ferner das, was dann bewirkt wird durch die Absonderung der Galle, was dann weiter durch die Tätigkeit von Leber und Milz geschieht, das alles gibt eben diese Abwehr der Eigennatur der äußeren Nahrungsstoffe. Daher sind also unsere Nahrungsmittel erst dann dem inneren Rhythmus des menschlichen Organismus angepaßt, wenn ihnen die Wirksamkeiten dieser Organe entgegengetreten sind. Und erst dann, wenn wir die in uns aufgenommenen Nahrungsmittel den Wirksamkeiten dieser Organe ausgesetzt und sie umgewandelt haben, haben wir dasjenige in uns, was fähig ist, in jenes Organsystem aufgenommen zu werden, das der Träger, das Werkzeug unseres Ich ist, in das Blut. Bevor irgendein äußerer Nahrungsstoff in unser Blut aufgenommen werden kann, so daß dieses unser Blut die Fähigkeit erhält, Werkzeug zu sein für unser Ich, müssen all die Eigengesetzlichkeiten der Außenwelt abgestreift sein, und das Blut muß die Nahrungsstoffe in einer solchen Gestalt empfangen, die der eigenen Natur des menschlichen Organismus entspricht. Daher können wir sagen: In Milz, Leber und Galle und in ihrem Zurückwirken auf den Magen haben wir diejenigen Organe, welche die Gesetze der äußeren Welt, aus der wir unsere Nahrung entnehmen, anpassen der inneren Organisation, dem inneren Rhythmus des Menschen.

Nun steht aber diese menschliche Natur, wie sie als Ganzes wirkt, mit allen ihren Gliedern nicht bloß der inneren Welt gegenüber, sondern diese innere menschliche Natur muß in einer fortwährenden Korrespondenz, in einem fortwährenden lebendigen Wechselwirken mit der Außenwelt sein. Dieses lebendige Wechselwirken mit der Außenwelt wird ja gerade dadurch abgeschnitten, daß den Gesetzen der Außenwelt, insofern wir mit ihr in Beziehung treten durch die Nahrungsstoffe, entgegengestellt werden die drei Organsysteme Leber, Galle, Milz. Durch diese wird die äußere Gesetzmäßigkeit weggenommen von innen her. Und es würde der menschliche Organismus, wenn er nur diesen Organsystemen ausgesetzt wäre, sich von der Außenwelt vollständig abschließen, er würde ein vollkommen in sich isoliertes Wesen sein. Daher ist ein anderes ebenso notwendig. Wie der Mensch auf der einen Seite solche Organsysteme braucht, durch welche die Außenwelt so umgestaltet wird, daß sie seiner Innenwelt gemäß wird, so muß er auf der anderen Seite auch in der Lage sein, unmittelbar mit dem Werkzeug seines Ich der Außenwelt entgegenzutreten, unmittelbar also seinen Organismus, der sonst eine in sich isolierte Wesenheit wäre, mit der Außenwelt in Beziehung zu setzen. Während das Blut auf der einen Seite mit der Außenwelt nur so in Beziehung tritt, daß es von dieser Außenwelt nur das erhält, dem alle Eigengesetzmäßigkeit abgestreift ist, tritt es auf der anderen Seite mit der Außenwelt so in Beziehung, daß es unmittelbar an sie herantreten kann. Das geschieht, wenn das Blut durch die Lungen fließt und mit der äußeren Luft in Berührung kommt. Da wird es durch den Sauerstoff der äußeren Luft aufgefrischt und in einer solchen Weise gestaltet, daß jetzt dieser Gestaltung nichts abschwächend gegenübertritt, so daß in der Tat der Sauerstoff der Luft so herantritt an das Werkzeug des menschlichen Ich, wie es dessen eigenster Natur und Wesenheit entspricht. So sehen wir jene ganz merkwürdige Tatsache vor unser Auge treten, daß das edelste Werkzeug, das der Mensch hat, das Blut, das Werkzeug seines Ich, wie ein Wesen dasteht, welches alle Nahrung sorgfältig filtriert erhält durch die früher charakterisierten Organsysteme. Dadurch ist das Blut in die Fähigkeit versetzt, ganz und gar ein Ausdruck der inneren Organisation des Menschen zu werden, des inneren Rhythmus des Menschen. Dadurch aber, daß das Blut unmittelbar in Berührung tritt mit denjenigen Stoffen der Außenwelt, die in seine innere Gesetzmäßigkeit und Regsamkeit aufgenommen werden dürfen, ohne daß sie unmittelbar bekämpft zu werden brauchen, dadurch ist diese menschliche Organisation nichts in sich Abgeschlossenes, sondern mit der Außenwelt voll in Berührung.

So haben wir im menschlichen Blutorganismus auch von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus etwas ganz Wunderbares vor uns. Wir haben in ihm ein wirkliches, echtes Ausdrucksmittel des menschlichen Ich, das ja in der Tat auf der einen Seite der Außenwelt zugekehrt ist, auf der anderen Seite dem eigenen Innenleben zugekehrt ist. So wie wir gesehen haben, daß der Mensch durch sein Nervensystem den Impressionen der Außenwelt zugewendet ist, also die Außenwelt sozusagen auf dem Umwege durch die Nerven in sich aufnimmt, so kommt er in eine unmittelbare Berührung mit der Außenwelt durch sein Blut, indem das Blut den Sauerstoff der Luft durch die Lungen aufnimmt. Daher können wir also sagen: In dem, was uns gegeben ist auf der einen Seite in dem Milz-Leber-Gallesystem und auf der anderen Seite in dem Lungensystem, haben wir zwei einander entgegenwirkende Systeme, die sich gleichsam berühren in dem Blut. Außenwelt und Innenwelt berühren sich durch das Blut ganz unmittelbar im menschlichen Organismus, indem das Blut von der einen Seite her mit der äußeren Luft in Berührung kommt und von der anderen Seite her mit den Nahrungsmitteln, denen ihre eigene Natur genommen ist. Es stoßen also, möchte man sagen, wie positive und negative Elektrizität, hier zwei Weltenwirkungen im Menschen zusammen. Und wir können uns sehr leicht vorstellen, wo das Organsystem liegt, welches bestimmt und geeignet ist, das Aufeinanderprallen dieser beiden Weltenkraftsysteme auf sich wirken zu lassen. Bis zum Herzen herauf, insofern das Blut durch das Herz strömt, wirken die umgewandelten Nahrungssäfte. Bis zum Herzen herein, insofern es vom Blute durchflossen wird, wirkt der Sauerstoff der Luft, der unmittelbar aus der Außenwelt in unser Blut tritt, so daß wir im Herzen dasjenige Organ haben, in dem sich diese zwei Systeme begegnen, in die der Mensch hineinverwoben ist, an denen er nach zwei Seiten hängt. Es ist mit diesem menschlichen Herzen so, daß wir sagen könnten: An ihm hängt auf der einen Seite der ganze menschliche innere Organismus, und auf der anderen Seite ist der Mensch durch das Herz unmittelbar angeknüpft an den Rhythmus, an die Regsamkeit der äußeren Welt.

Wenn nun zwei solche Systeme zusammenstoßen, so könnte es ja sein, daß ihr Zusammenwirken eine unmittelbare Harmonie ergäbe. Wir könnten uns vorstellen, daß diese zwei Systeme - das System der großen Welt, das durch den aufgenommenen Sauerstoff oder die Luft überhaupt in uns hineinwirkt, und das System der kleinen Welt, unseres eigenen inneren Organismus, das uns die Nahrungsmittel umwandelt -, daß sich diese Systeme im Blute, indem es das Herz durchströmt, einen harmonischen Ausgleich schaffen. Wenn es so wäre, dann wäre der Mensch eingespannt in zwei Welten, die sozusagen sein inneres Gleichgewicht schüfen. Nun werden wir im Laufe dieser Vorträge noch sehen, daß es sich mit der Beziehung der Welt zur menschlichen Wesenheit nicht so verhält. Es ist vielmehr so, daß die Welt sich sozusagen ganz passiv verhält, daß sie nur ihre Kräfte aussendet und es dem Menschen überläßt, durch eigene innere Tätigkeit den Ausgleich zu schaffen zwischen den zweierlei Systemen, in deren Wirkungen wir eingespannt sind. Wir werden es immer mehr und mehr als das Wesentliche erkennen lernen, daß dem Menschen zuletzt immer ein Rest bleibt für seine innere Tätigkeit, daß es ihm — bis in seine Organe hinein — überlassen ist, den Ausgleich, das innere Gleichgewicht selber zu schaffen. So müssen wir auch im menschlichen Organismus selber den Ausgleich, die Harmonisierung dieser beiden Weltsysteme suchen. Wir müssen uns von vornherein sagen: Durch die Gesetzmäßigkeiten der Außenwelt, die direkt in den Menschen hineintreten, und durch die eigenen inneren Gesetzmäßigkeiten des Menschen, in die er die Gesetzmäßigkeiten der Außenwelt umwandelt, welche er aufnimmt durch die Nahrung, ist noch nicht ohne weiteres die Harmonisierung der beiden Systeme gegeben. Die Harmonisierung muß sich erst durch ein besonderes eigenes Organsystem vollziehen. Der Mensch muß in sich selber die Harmonisierung herbeiführen. Das geschieht nicht in bewußten Vorgängen, sondern durch Vorgänge, die sich ganz unbewußt innerhalb des menschlichen Organismus abspielen. Dieser Ausgleich zwischen diesen beiden Systemen wird dadurch herbeigeführt, daß zwischen dem Milz-Leber-Gallesystem auf der einen Seite und dem Lungensystem auf der anderen Seite, die sich in dem das Herz durchströmenden Blute gegenüberstehen, eingeschaltet ist dasjenige, was wir das Nierensystem nennen, das auch in inniger Verbindung steht mit dem Blutkreislauf.

Im Nierensystem haben wir dasjenige, was sozusagen harmonisiert jene äußeren Wirkungen, die von dem unmittelbaren Berühren des Blutes mit der Luft herrühren, mit den Wirkungen, die von denjenigen inneren Organen des Menschen ausgehen, durch die die Nahrungsstoffe erst zubereitet werden müssen, damit ihre Eigennatur abgestreift wird. In dem Nierensystem haben wir also ein solches ausgleichendes System, durch das der Organismus in die Lage kommt, den Überschuß abzugeben, der sich ergeben würde durch ein unharmonisches Zusammenwirken der beiden anderen Systeme.

Damit haben wir der ganzen inneren Organisation — den Organen des Verdauungsapparates einschließlich derjenigen Organe, die wir dazurechnen müssen, wie Leber, Galle und Milz — dasjenige gegenübergestellt, wofür diese Organe zunächst ihre vorbereitende Tätigkeit entwickelt haben, das Blutsystem. Und wir haben auf der anderen Seite diesem Blutsystem diejenigen Organe gegenübergestellt, durch welche der einseitigen Isolierung entgegengearbeitet und damit der Ausgleich geschaffen wird zwischen dem genannten inneren System und dem, was von außen her kommt. Wenn wir also — und wir werden noch sehen, wie sehr das berechtigt ist — das Blutsystem mit seinem Mittelpunkt, dem Herzen, uns in die Mitte des Organismus hineingestellt denken, so haben wir, sich angliedernd an dieses Blut-Herzsystem, auf der einen Seite das Leber-Galle-Milzsystem, auf der anderen Seite — und auf andere Weise mit dem Herzen in Verbindung stehend — das Lungensystem. Dazwischen ist das Nierensystem angeordnet. Wir werden später noch sehen, wie ungemein interessant der Zusammenhang ist zwischen dem Lungensystem und dem Nierensystem. Jetzt wollen wir darauf zunächst nicht näher eingehen, sondern das Ganze im Zusammenhang betrachten. Wenn wir die Systeme einfach ganz schematisch nebeneinander zeichnen (Zeichnung Seite 78 links), dann erkennen wir schon aus dieser schematischen Darstellung, wie die menschliche innere Organisation in einem gewissen Zusammenhange steht, und wir haben diesen Zusammenhang so dargestellt, daß wir in dem Herzen mit dem dazugehörigen Blutsystem das Allerwichtigste zu sehen haben.

Nun habe ich schon darauf hingewiesen - und wir werden noch im genaueren sehen, inwiefern eine solche Namengebung gerechtfertigt ist — daß im Okkultismus die Milzwirkung als eine saturnische Wirkung bezeichnet wird, die Leberwirkung als eine Jupiter- und die der Galle als eine Marswirkung. Aus demselben Grunde sieht nun die okkulte Erkenntnis in dem Herzen und dem dazugehörigen Blutsystem dasjenige, was den Namen «Sonne» im menschlichen Organismus ebenso verdient wie die Sonne draußen innerhalb des Planetensystems. Das Lungensystem bezeichnet der Okkultist nach demselben Prinzip als «Merkur» und das Nierensystem mit dem Namen «Venus». So haben wir schon in der Benennung dieser Systeme des menschlichen Organismus — wenn wir jetzt auch gar nicht eingehen auf eine Rechtfertigung dieser Namen — etwas angedeutet wie ein inneres Weltsystem, was wir noch dadurch ergänzt haben, daß wir uns in die Lage versetzten, auch den Zusammenhang der beiden Organsysteme zu betrachten, die zum Blutsystem in Beziehung stehen. Erst wenn wir die Zusammenhänge in diesem Sinne betrachten, tritt uns das in einer Vollständigkeit entgegen, was wir die eigentliche menschliche innere Welt nennen können. Ich werde Ihnen nun in den folgenden Vorträgen auch noch zu zeigen haben, daß tatsächlich der Okkultist Gründe hat, das Verhältnis der Sonne zu Merkur und Venus in einer ähnlichen Weise sich vorzustellen, wie im menschlichen Organismus das Verhältnis zwischen Herz, Lungen und Nieren gedacht werden muß.

Wir sehen daraus, daß in dem Werkzeug unseres Ich, in unserem Blutsystem, das seinen Rhythmus im Herzen zum Ausdruck bringt, etwas gegeben ist, was gewissermaßen in seiner ganzen Gestaltung, in seiner inneren Natur und Wesenheit durch das innere Weltsystem des Menschen bestimmt wird, und daß es in ein solches [makrokosmisches] Gesamtsystem eingebettet sein muß, damit es so leben kann, wie es eben lebt. In diesem menschlichen Blutsystem — das habe ich schon öfter erwähnt — haben wir zu sehen das physische Werkzeug unseres Ich. Wir wissen ja, daß unser Ich, so wie wir es haben, nur dadurch möglich ist, daß dieses Ich aufgebaut ist auf Grundlage eines physischen Leibes, eines Ätherleibes und eines Astralleibes. Ein frei in der Welt herumfliegendes menschliches Ich ist innerhalb der Welt, die unsere Welt ist, nicht denkbar. Ein menschliches Ich setzt voraus als Grundlage einen Astralleib, einen Ätherleib und einen physischen Leib. Wie nun dieses Ich in geistiger Beziehung die drei genannten Wesensglieder des Menschen voraussetzt, so setzt sein physisches Organ, das Blutsystem, auch physisch solche Abbilder des astralischen und des ätherischen Leibes voraus. Das Blutsystem kann sich also nur auf der Grundlage von etwas anderem entwickeln. Während die Pflanze sich einfach entwickelt auf der Grundlage der sie umgebenden unorganischen Natur, indem sie gleichsam aus derselben herauswächst, müssen wir sagen, daß für den menschlichen Blutorganismus als Grundlage nicht ohne weiteres bloß die äußere Natur als Unterlage nötig ist, sondern es muß diese äußere Natur erst noch eine Umgestaltung erfahren. Wie der physische Leib des Menschen erst einen Ätherleib und einen Astralleib haben muß, so muß das, was an Nahrungsstoffen einströmt, erst umgestaltet werden, damit es dem menschlichen Ich als Werkzeug dienen kann.

Wenn wir nun auch sagen können, daß dieses physische Werkzeug des menschlichen Ich, das Blut, durch die Lunge von außen bestimmt wird, so ist die Lunge selber doch ein Organ der physischen Leibesorganisation, das heißt, es ist nicht dieses Organ, sondern die durch dasselbe eingeatmete Luft, welche es möglich macht, mit einem äußeren Rhythmus auf das Blut einzuwirken. Wir müssen unterscheiden zwischen dem, was von außen an den Menschen herankommt in Form der Luft, die eingeatmet wird und die es dem Menschen möglich macht, mit einem äußeren Rhythmus unmittelbar sein Blutsystem zu durchdringen, und dem, was nicht unmittelbar an das lebendige Werkzeug des Ich im Organismus, an das Blut, herantritt, sondern was herantritt - in der Art, wie es schon charakterisiert worden ist - auf dem Umwege durch die Seele, was der Mensch also dadurch aufnimmt, daß er die Eindrücke der Außenwelt durch die Sinne empfängt und diese Sinne dann ihre Eindrücke auch vermitteln bis zur Bluttafel hin. Deshalb werden wir sagen können: Der Mensch tritt nicht bloß mit der Außenwelt unmittelbar stofflich in Berührung durch die Atmungsluft, indem diese Berührung hereinwirkt bis auf sein Blut, sondern er tritt durch die Sinnesorgane mit der Außenwelt auch so in Berührung, daß diese Berührung eine nichtstoffliche ist, wie sie in dem Prozeß der Wahrnehmung stattfindet, den die Seele entfaltet, wenn sie zur Umwelt in Beziehung tritt. Da haben wir etwas, was sich als ein höherer Prozeß hinzufügt zum Atmungsprozeß, wir haben etwas wie einen vergeistigten Atmungsprozeß. Während wir durch den Atmungsprozeß die Außenwelt stofflich aufnehmen, nehmen wir im Wahrnehmungsprozeß — und ich meine jetzt mit «Wahrnehmung» alles, was der Mensch an äußeren Impressionen verarbeitet — etwas durch einen vergeistigten Atmungsprozeß in unseren Organismus auf. Und es entsteht jetzt die Frage: Wie wirken diese beiden Prozesse zusammen? Denn im menschlichen Organismus muß alles aufeinander einwirken.

Legen wir uns einmal diese Frage genauer vor — denn es wird Wesentliches davon abhängen, daß wir sie uns genau vorlegen -, um uns die heute zunächst hypothetisch zu gebende Antwort vor unsere Seele führen zu können. Wir müssen uns darüber klar werden, wie ein Zusammenwirken, ein Wechselwirken stattfinden kann zwischen alle dem, was durch das Blut wirkt und was es geworden ist dadurch, daß alle diese inneren Organprozesse stattgefunden haben, und dem, was das Blut wird, indem wir äußere Wahrnehmungsprozesse vollziehen. Wir müssen sehen, daß da eine Wechselwirkung stattfinden kann. Das Blut ist, trotzdem es so eingehend und so vielseitig filtriert ist, trotzdem so vieles dafür gesorgt hat, daß es ein so wunderbar organisierter Stoff ist, der Werkzeug unseres Ich sein kann, das Blut ist trotzdem eine physische Substanz und gehört als solche zum physischen Leibe. Daher können wir sagen: Zunächst erscheint uns ein weiter, weiter Abstand zwischen dem, was im menschlichen Blute an physischen Prozessen wirkt, und dem, was wir als unsere Wahrnehmungsprozesse kennen, die die Seele vollzieht. Das ist eine nicht abzuleugnende Realität; denn der Mensch müßte ja auf sonderbare Weise nicht zu denken verstehen, der ableugnen wollte, daß Wahrnehmungen, Begriffe, Ideen, Gefühle, Willensimpulse ebenso etwas Reales sind wie Blutsubstanz, Nervensubstanz, Lebersubstanz, Gallensubstanz und so weiter. Wie diese Dinge zusammenhängen, darüber können sich die Weltanschauungen streiten; sie können sich darüber streiten, ob die Gedanken bloß irgendwelche Wirkungen, sagen wir, der Nervensubstanz oder dergleichen seien. Da kann vielleicht ein Streiten der Weltanschauungen beginnen. Aber keinen Streit kann es darüber geben, weil es eine selbstverständliche Sache ist, daß unser Seeleninnenleben, unser Gedankenleben, unser Gefühlsleben, alles was sich aufbaut auf Grund der äußeren Wahrnehmungen und Eindrücke, eine Realität für sich darstellt. Wohlgemerkt, ich sage nicht: eine abgesonderte Realität —, sondern: eine Realität für sich, denn nichts ist in der Welt abgesondert. Mit «Realität für sich» soll nur angedeutet werden, was real beobachtet werden kann, und dazu gehören Gedanken, Gefühle und so weiter ebenso wie Magen, Leber, Galle und Milz.

Aber ein anderes kann uns auffallen, wenn wir diese zwei Realitäten nebeneinanderstellen: Auf der einen Seite alles, was ein selbst noch so stark filtriertes Materielles, Physisches ist wie das Blut, und auf der anderen Seite das, was ja mit einem Physischen gar nichts zu tun zu haben scheint zunächst, nämlich die Inhalte der Seele, die Gefühle, Gedanken und so weiter. In der Tat bietet der Anblick dieser zweierlei Arten von Realitäten für den Menschen solche Schwierigkeiten, daß sich an diesen Anblick angegliedert haben die allermannigfaltigsten Antworten aus den verschiedensten Weltanschauungen heraus. Da gibt es Weltanschauungen, welche eine unmittelbare Einwirkung des Seelischen, des Gedanklichen, des Gefühlsmäßigen auf die physische Substanz annehmen, wie wenn der Gedanke unmittelbar auf die physische Substanz wirken könnte. Denen stehen andere gegenüber, die materialistischen, die annehmen, daß Gedanken, Gefühle und so weiter einfach produziert werden aus den Vorgängen des Physisch-Substantiellen heraus. Der Streit dieser beiden Weltanschauungen hat ja in der äußeren Welt - nicht für den Okkultisten, für den dieser Streit ein Streit mit leeren Worten ist — durch lange Zeiten hindurch eine große Rolle gespielt. Und als man endlich gar nicht mehr zurechtgekommen ist, da ist in der neueren Zeit noch etwas anderes aufgetreten, was den sonderbaren Namen «psychophysischer Parallelismus» führt. Weil man sich gar nicht mehr zu helfen wußte, welcher nun von den beiden Gedanken der richtige ist — entweder wirkt der Geist auf die leiblichen Prozesse, oder es wirken die leiblichen Prozesse auf den Geist —, so sagte man eben einfach, das seien zwei Vorgänge, die parallel ablaufen. Man sagte sich: Während der Mensch denkt, fühlt und so weiter, laufen parallel in seinen physischen Organsystemen ganz bestimmte Vorgänge ab. - Die Wahrnehmung «Ich sehe Rot» würde also entsprechen irgendeinem materiellen Vorgang innerhalb des Nervensystems. Was wirempfinden beieinem roten Eindruck, was wir fühlen an Freude oder Schmerz bei ihm, entspricht einem materiellen Vorgang. Aber weiter geht man nicht, als zu sagen, daß er eben «entspricht». Diese Theorie hebt in der Tat die ganzen Schwierigkeiten auf, indem sie diese einfach wegexpliziert. Nun, alle Streitereien, die sich auf diesem Boden entsponnen haben und auch die Hilflosigkeit des psychophysischen Parallelismus ergeben sich daraus, daß man diese Fragen entscheiden will auf einem Boden, auf dem sie gar nicht ausgetragen werden können. Wir haben es mit nichtmateriellen Vorgängen zu tun, wenn wir die Tätigkeiten unseres inneren Seelenlebens ins Auge fassen, und wir haben es mit materiellen Vorgängen zu tun, wenn wir, selbst über etwas so fein organisiertes wie es das Blut ist, unsere Betrachtungen anstellen. Wenn man diese zwei Dinge einfach gegenüberstellt - physische Betätigung und seelische Betätigung — und jetzt durch Nachdenken herausbekommen will, wie diese beiden aufeinander wirken, so ergibt dieses Nachdenken eben gar nichts. Durch Nachdenken kann man alle willkürlichen Lösungen oder Nichtlösungen finden. Erst dadurch wird über diese Fragen etwas entschieden werden können, daß wir uns wirklich eine höhere Erkenntnis aneignen, die weder stehenbleibt bei dem physischen Anschauen der Außenwelt noch bei dem an die bloße physische Außenwelt gebundenen Denken. Wir müssen eine Form der Erkenntnis finden, die sich erhebt zu dem, was über das Physische hinaus in die überphysische Welt führt. Wir müssen auf der einen Seite von dem Materiellen hinaufsteigen zu dem Übermateriellen, zu dem Überphysischen, wir müssen aber auf der anderen Seite auch von dem Seelenleben, das sich in der physischen Welt abspielt, hinaufsteigen zu dem, was unserem Seelenleben zugrundeliegt in der überphysischen Welt, denn mit unserem Seelenleben, mit allen unseren Gefühlen und so weiter leben wir ja auch in der physischen Welt. Wir müssen also von zwei Seiten her aufsteigen zu einer überphysischen Welt.

Um von der materiellen Seite her in die überphysische Welt aufzusteigen, dazu sind jene Seelenübungen notwendig, welche es dem Menschen möglich machen, hinter das äußere Sinnliche zu schauen, hinter den Schleier, von dem ich gesprochen habe, in welchen unsere Sinneseindrücke hineinverwoben sind. Solche Sinneseindrücke haben wir ja auch dann vor uns, wenn wir den äußeren menschlichen Organismus betrachten, auch bei dem am feinsten Organisierten des menschlichen Organismus, dem Blute, haben wir es mit einem Physisch-Sinnlichen zu tun. Es sind Seelenübungen notwendig, um den Menschen in die übersinnliche Welt hineinzuführen. Zunächst muß er eine Stufe tiefersteigen als dort, wo er war, als er die Seeleneindrücke in sich aufnehmen konnte, unter den Plan des Physischen. In den Untergründen der physisch-sinnlichen Welt, da tritt ihm als das Übersinnliche der menschlichen Organisation der Ätherleib entgegen. Dieser Ätherleib - wir werden ihn noch genauer besprechen gerade vom okkult-physiologischen Standpunkte aus - ist eine übersinnliche Organisation, die wir uns zunächst einfach denken als die übersinnliche Grundsubstanz, aus der sich der sinnliche Organismus des Menschen herausgliedert und von dem er ein Abbild, ein Abdruck ist. Von diesem Ätherleibe ist selbstverständlich auch das Blut ein Abdruck. Wir haben also jetzt hier, indem wir um eine Stufe hinter den physisch-sinnlichen Organismus getreten sind, ein übersinnliches Glied in dem menschlichen Ätherleibe gefunden. Und es fragt sich nun: Können wir an dieses Übersinnliche, an diesen Ätherleib, nun auch herankommen von der anderen Seite her, von der Seite des Seelischen her, von unseren Empfindungen, Gedanken, Gefühlen her, die wir uns aufbauen aus Eindrücken der Außenwelt?