An Occult Physiology

GA 128

22 March 1911, Prague

3. Co-operation in the Human Duality

These first three lectures, including to-day's, are intended to orient us in a general way in regard to what must be considered in connection with the life of man, with his true being. For this reason some of the more important concepts first given out are, in a sense, left hanging in the air, since the more detailed exposition of these will naturally have to follow later. But it is better to make a general survey of the whole method of occult observation of the human being and afterwards to build into our study, which for the present we accept only as hypothetical, that which will then appear to us as its deeper foundations.

I have already dwelt upon one matter, at the close of yesterday's lecture. I there endeavoured to show that, by means of certain soul-exercises, by means of strict concentration of thought and feeling, the human being can call forth a state of life different from the ordinary one. The ordinary state expresses itself as it does because in our fully waking day consciousness, we have a normal connection between the nerves and the blood. That which happens by way of the nerves inscribes itself upon the tablet of the blood. By means of soul-exercises, a man may reach the point where he can so completely control the nerve that it does not extend its activity as far as the blood. This activity is thrown back into the nerve itself. But now, because the blood is the instrument of the ego, a person who does this, who has freed his nerve-system from the course of the blood through strict concentration of feeling and thought, feels as if he were estranged from his own accustomed being, lifted out of it. He feels as if he now stood facing himself, with the result that he can no longer say to this familiar being of his, “This is I”; he must say, “That is you.” Thus he stands facing his own Self just as he might face any unfamiliar person living in the physical world.

A man like this, who has become in a certain sense clairvoyant, feels as if a higher order of being were towering up in his soul-life. This is an entirely different feeling from that which a man has when he confronts the ordinary world. When he confronts the external world, he feels that he stands as a stranger facing the things and beings of this external world, the animals, the plants, etc.—as a being who stands beside them or outside them. He knows quite definitely when he has a flower before him: “The flower is there, and I am here.” It is otherwise when, as a result of the liberation from his nerve-system, he ascends into the spiritual world, when he lifts himself out of his ego. He does not any longer feel in that case: “There is the plant-being that faces me, and here am I,” but rather as if the other being entered completely into him, and as if he felt himself one with it. Thus we may say that the clairvoyant human being learns, through advanced power of observation, to know the spiritual world—that spiritual world with which man is, indeed, united and which to a certain extent, comes to meet him by way of the nerve-system, even though in normal life this occurs by the indirect road of the sense-impressions. It is the spiritual world, therefore, about which the human being in his ordinary consciousness at first knows nothing, and it is this same spiritual world which, nevertheless, actually inscribes itself upon the tablet of our blood, hence upon our ego. In other words, we may say that underlying everything that surrounds us externally in the world of sense there lies a spiritual world, so that we see as though through a veil woven by the sense-impressions. In our normal consciousness, which is compassed by the horizon of our ordinary ego, we do not see the spiritual world lying behind this veil. The moment, however, that we free ourselves of the ego, the ordinary sense-impressions disappear also. We then begin to live in a spiritual world above us, that same world that exists in reality behind the sense-impressions, and with which we become one when we lift our nerve-system out of our ordinary blood-system.

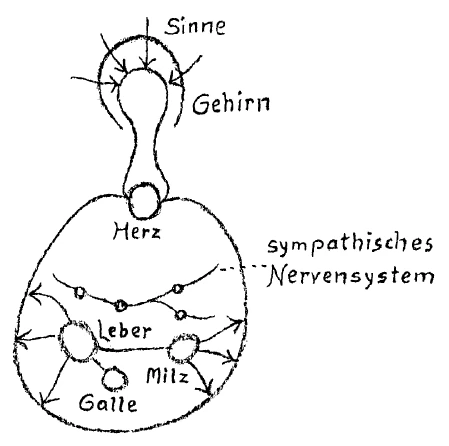

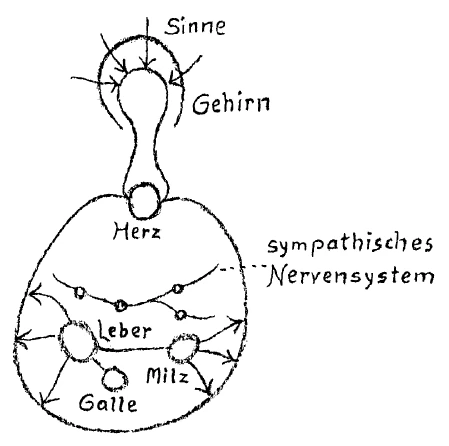

We have now followed in a manner the process of human life, how it is stimulated from the external world and how it carries on its work through the nerves and the blood. At the same time, we have called attention to the fact that we can see in the purely organic, physical inner life of man a kind of “compressed outside world”; and we have pointed in particular to the fact that such an outside world, condensed into organs, is present in our liver, our gall-bladder, and our spleen. We may say, therefore, that just as the blood in the one direction, in the upper extremity of our organism, courses through the brain in order there to come into contact with the outside world (this takes place by reason of the fact that the external sense-impressions work upon the brain) just so, as it circulates through the body, does it come into relationship with the inner organs among which we have first considered the liver, the gall-bladder, and the spleen. The blood does not in these organs come into contact with any sort of outside world because they do not open outward as do the organs of sense, but are enclosed within the organism, are covered on all sides and consequently develop only an inner life. Moreover, these organs can act upon the blood only in accordance with their own nature as liver, gall-bladder, spleen. They do not, like the eye or the ear, receive outside impressions, and they cannot, therefore, pass on to the blood influences stimulated from outside, but can simply express their own particular natures through whatever effect these may have upon the blood. When we observe this inner world into which the outside world is condensed, as it were, we may state that here an outer world which has become an inner world acts upon the human blood where it can act at all.

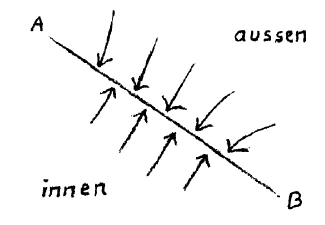

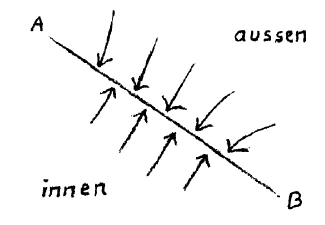

If we draw a sketch of this, and represent the tablet of the blood by the line A B, we have to represent everything which comes from outside as now directed in a certain sense inward, and pressing from the one direction against the tablet of the blood, while being, as it were, inscribed upon one side of the tablet, whereas everything coming from the inside we have to think of as approaching from the other direction and inscribing itself on the other side of the tablet. Or doing it less schematically, we might then take the human head and observe the blood as it courses through this in such a way that we say: “It is being written upon from outside through the sense-organs; and the brain, in performing its task, has the same sort of transforming influence upon the blood as the inner organs have.” For these three organs, the liver, the gall-bladder and the spleen, work, as we know, from the opposite direction, from the other side, upon the blood flowing into them. Thus it would seem that the blood may be able to receive radiations and influences from the inner organs, and by this means, supposing this to be possible, it can, as the instrument of the ego, bring to expression in this ego the inner life of these organs, just as everything which surrounds us in the world outside finds expression in the life of our brain.

At this point we must understand clearly, that something else very definite must happen to make possible the action of these organs upon the blood. Let us remember that we had to assert that only through the reciprocal activity, through the connection between the nerve and the course of the blood, can there be any possibility whatever that anything will be inscribed upon the blood, that any influence can be exercised upon it. If therefore from the other direction, from the inner side, influences are to be exercised upon the blood, if the inner organs, or what we may call man's inner cosmic system, are to work upon the blood, there must be inserted between these organs and the blood something similar to a nerve-system. The “inner world” must first be able to act upon a nerve-system if it is to carry its activity over to the blood. Thus we see, by simply comparing the lower portion of the human being with the upper, that we are forced to presuppose that something in the nature of a nerve-system must be inserted between the circulating blood and our inner organs—among which we have here these three representative ones, the liver, the gallbladder, and the spleen.

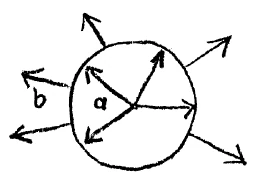

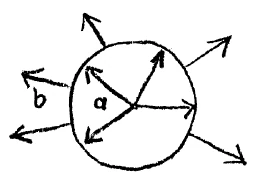

External observation shows us that this really is the case, that in all these organs is inserted what is called the “sympathetic nervous system” which extends throughout the bodily cavity of man, and which stands in a relationship to his inner world and to the course of the blood similar to that in which the nervous system of the spinal cord stands to the great outside world and to the life of man, to the circulation of his blood. This sympathetic nervous system passes first along the spine and, going out from there, traverses the most widely separated parts of the organism and branches out, spreading into reticular forms, especially in the abdominal cavity, where one part of it goes by the popular name of the “solar plexus.” We may expect to find a certain variation of this system from the other nerve-system. It is always interesting, even if it should not serve as any proof, to ask ourselves: What would be the relation between this nerve-system and the nerve-system of the spinal cord if those conditions should be fulfilled which we have for the present asserted hypothetically? It would be obvious that, just as the nerve-system of the spinal cord must open itself to surrounding space, so would this sympathetic nerve-system have to incline toward what is compressed into the inner organisation. Thus the nerve-system of the spinal cord is related to the sympathetic nerve-system, that is, if the facts agree with our presuppositions, somewhat as lines radiating outward in all directions from the circumference of a circle (a) would be related to those radii that we might direct away from the centre of the circle toward its circumference (b). In a certain sense, therefore, there would have to be an antithesis between the sympathetic nerve-system and the nerve-system of the brain and spinal cord. This antithesis actually does exist. We see here that it may be of great value to us to be able to point to the fact that, if our assumptions are correct, experience and observation will in a manner confirm them. And, when we turn our attention again to what we have been observing, it is evident that external observation does confirm the suppositions we have formed. We find that, whereas in the case of the sympathetic nerve-system the essential thing is that ganglia of a certain kind form themselves which are strong and large, while the connecting filaments radiating out from these are relatively small and of little account in contrast to these ganglia, exactly the reverse is true in the case of the nerve-system of the brain and spinal cord. There the connecting threads are the important thing, whereas the ganglia have a subordinate significance.

Thus our observation does, in fact, confirm what we accepted as a supposition, and we can now make the following assertion. If the function of the sympathetic nerve-system must consist in carrying over to the blood the inner life of the human organism, which expresses itself in the nourishing and the warming through of the organism, and which pours itself into the sympathetic nerves, in exactly the same way in which the outer impressions are carried over to the tablet of the blood by means of the nerve-system of the brain and spinal cord, in that case we obtain through the instrument of the ego, which is the blood, by the roundabout way of the sympathetic nerve-system, the impressions of our own inner body. Since however this inner body of ours, like everything physical, is built up out of the spirit, we therefore take up into our ego, by the roundabout road of the sympathetic nerve-system, what has been condensed as spiritual world into the corresponding organs of the inner world of man.

Thus we see here also, strangely enough, how that duality in the human being with which we began our studies is expressed in even greater exactness. We see the world at one moment outside; at another moment we see it inside. Both times we see this world working in such a way that it uses a nerve-system as the instrument of its work. We see that in the centre, between the outside world and the inside world, is placed our blood-system which exposes its two sides, to be written upon like a tablet, sometimes from outside, sometimes from inside.

We said yesterday and repeat to-day for the sake of clarity, that the human being is in position to free his nerves, in so far as these lead to the outside world, from their action upon the blood-system. We must now put the question, whether something similar is possible also in the other direction. And we shall see later that it is possible, as a matter of fact, to practise also other exercises of the soul that are capable of producing in the other direction the same effect as that of which we have spoken. There is one difference, however, in connection with the effect produced in this other direction. Whereas we are able through concentration of thought, concentration of feeling, and occult exercises, to set free from the blood the nerves of our brain and spinal cord, we are able, on the other hand, by means of such concentrations as go right down into our inner life, our inner world—by which is meant in particular that sort of concentration included under the term “the mystical life,”—to penetrate so deep down within ourselves that in doing so we most certainly do not ignore our ego, nor therefore its instrument the blood. The mystical immersion, concerning which we know that by its means a man plunges down, so to speak, into his own divine being, into his own spirituality in so far as this is alive in him, this mystical immersion is not primarily a lifting of oneself out of the ego. It is rather a positive plunging of oneself down into the ego, a strengthening or energising of the ego-feeling. We can convince ourselves of this if we set aside what the mystics of the present day may say, and consider to some extent the earlier mystics.

These earlier mystics, whether they had for their foundation more of reality or less matters not, endeavoured, above all things, to penetrate into their own ego and to look away from everything which the outside world could offer, in order to be free from all external impressions and to plunge down completely into themselves. This inward self-communion, this diving down into one's own ego, is primarily a concentration or drawing down of the entire force and energy of the ego into one's own organism. This now works further upon the entire organisation of the human being; and we may say that this inward immersion, which may be called in the true sense of the term the “mystic path,” is in direct contrast to that other path leading out into the macrocosm, so that we do not draw the instrument of the ego, which is the blood, away from the nerve, but on the contrary thrust it more than ever against the sympathetic nerve-system. Whereas, therefore, we loosen by means of the process described yesterday the connection between the nerve and the blood, we here strengthen the connection between the blood and the sympathetic nerve-system by means of true mystic immersion.

This is the physiological counterpart: that the blood is here pressed in more than ever against the sympathetic nerve-system whereas, when the wish is to reach the spiritual world in the other way, the blood is pushed away from the nerve. Thus we see that what can take place in the mystic immersion is primarily an impressing of the blood upon this inner, sympathetic nerve-system.

Now, let us suppose that we might disregard what happens when a man thus enters into his inner being, when he does not free himself from his ego, but presses down, on the contrary, into the ego, and takes with him at the same time all his less desirable qualities. For when a man frees himself from his ego he leaves the ego behind with all these less desirable qualities; but when he immerses himself into his ego it is not at all certain, to begin with, that he does not at the same time press down all his undesirable characteristics into this energised ego of his: in other words, that everything contained in his passionate blood is not pressed down with the blood into the sympathetic nerve-system. But let us suppose that we might for the time being disregard all this, and assume that the mystic has taken care, before coming to any such mystic immersion, that his less desirable qualities shall have disappeared more and more and that, in place of these egoistic qualities, selfless, altruistic feelings have appeared; that he has prepared himself by endeavouring to bring to life within himself a feeling of compassion for all things possessed of being to the end that, by means of the selfless qualities that have thus been called forth for all beings, he may paralyse these other qualities that take account only of the ego. Let us suppose, then, that the man has prepared himself sufficiently for this immersion within his own inner being. He carries his ego in that case by means of the instrument of his blood down into his own inner world. It then comes to pass that his inner nerve-system, the sympathetic nerve-system, about which the human being in his normal consciousness knows nothing, presses its way into the ego-consciousness, so that he begins to know: “I have within me something which can mediate to me the inner world in the same way that the other nerve-system mediates to me the outer world.”

Thus man descends into his own being and becomes aware, so to speak, of his sympathetic nerve-system. And just as he can know, by means of the outer nerve-system of the brain and spinal cord, the outside world that forms his environment, so there now comes to meet him that inner world which has built itself up within him. Moreover, just as we do not see the nerves, since no one sees the optic nerve, but rather that which is to be seen by means of the nerve, the external world that penetrates into our consciousness, just so also in the case of the mystic immersion it is not, to begin with, the inner nerves that penetrate the consciousness, for the human being is aware only that he has in these an instrument through which he can behold what is within him. It is indeed, something quite different that appears. Now that he has brought his faculty of cognition to an inward clairvoyance, his inner world appears before him. Just as the outward-directed look discloses to us the outer world, and our nerves do not in the process come into our consciousness, so likewise it is not our sympathetic nerve-system that comes into our consciousness, but obviously that which confronts us as “inner world.” Only, this inner world which here comes into our consciousness is really our own Self as physical man.

Perhaps it is not so much to the point here, but I should feel inclined to suggest that a thinker who is the least materialistic might, indeed, sense a feeling of horror rising up within him if he were to say to himself: “In that case I can see my own organism inside me!” And what he might mean, perhaps, would be: “How wonderful, to become clairvoyant by means of my sympathetic nerve-system and to be able to see my own liver, gall-bladder, and spleen!” As I remarked, this is not necessarily to the point, yet someone might say such a thing. But the facts are otherwise. For, in making an objection like this, such a person would fail to take into account that what the human being ordinarily calls in external life his liver, his gall-bladder, and his spleen is viewed from outside, just like all other external objects. In ordinary life we are obliged to view the human organism through the external senses, the outer nerves. What we may learn to know in anatomy, in the usual physiology, as liver, gall-bladder, and spleen constitutes these organs as seen from outside by means of the nerve-system of the brain and spinal cord. There they are viewed in exactly the same way in which one views anything externally. The position is entirely different, however, when a man can see clairvoyantly inside himself by means of the sympathetic nerve-system. He does not in that case see at all the same things that one sees when looking from outside; rather, he now sees something which caused the seers throughout the ages to choose such strange names as those I cited in the second lecture.

He is now aware that in reality, to external sight which uses the brain and the spinal cord, these organs appear in Maya, in external illusion, because the aspect they offer outwardly does not show them in their inner essential significance. He sees, in fact, something entirely different when he is able to observe this his inner world from the opposite direction, but now with the use of an inwardly clairvoyant eye. He now gradually realises why the seers of all times connected the activity of the spleen with the action of Saturn, the activity of the liver with the action of Jupiter, and the activity of the gallbladder with the action of Mars. For what he thus sees in his own inner self is, indeed, fundamentally different from what presents itself to the external view. He becomes aware that he actually has before him portions of the outside world enclosed within the boundaries of his inner organs.

And one thing now becomes particularly clear, which may serve us chiefly as an example for this method of arriving at knowledge, enabling us to see what course these ways of attaining knowledge follow in the life of the organism, in leading us beyond the customary views. In this case we can convince ourselves especially with regard to one fact, namely, how very significant an organ the human spleen is. Indeed, this organ really appears to inner observation as if it did not consist of an externally visible substance, of fleshly matter, but rather, if the expression may be permitted, although it approximates only to what can actually be observed, as if it actually were a luminous cosmic body in miniature with every possible sort of inner life, and indeed an inner life highly complicated.

Yesterday I called your attention to the fact that the spleen, externally observed, may be described as a plethoric tissue with minute white corpuscles embedded in it, so that it is legitimate, perhaps, from the point of view of external observation, to assume that the blood which flows through the spleen is strained through it as if through a sieve. When this spleen is observed inwardly, on the other hand, it appears above all to be an organ which, by means of the manifold inner forces already mentioned, is brought into a continual rhythmic movement. We convince ourselves even in connection with such an organ as this that a very great deal in the world is, as a matter of fact, dependent upon rhythm. An intimation of the importance of rhythm in the entire life of the world may be felt when we recognise it also externally in the pulse-beat of the blood. In that case, however, it is externally that we recognise it. But we can follow it externally also in the spleen. For it is possible here to follow it rather exactly, and we can also look for confirmation of what has been said through external observation. To inward clairvoyant sight all the differentiations of the spleen, which take place as if in a luminous body, are there in order to give this spleen a certain rhythm in life. This rhythm differs very considerably from other rhythms that we perceive elsewhere in life. Indeed it is just here, in the case of the spleen, that it is interesting to observe how very noticeably this rhythm differs from others: that is, it is far less regular than the other rhythms of which we shall speak later. This is due to the fact that the spleen lies near the human nutritive apparatus, and has something to do with this.

Now, you will be able to understand me if you consider how amazingly regular the rhythm of the blood must be in the human being in order that life may be properly sustained. This must be a very regular rhythm. But there is another rhythm that is regular only to a very slight degree—although one could wish that, through self-education of the human being, it might become more and more regular especially in the life of the child—namely, the rhythm of eating and drinking. Any man of moderately regular habits does, to be sure, keep a certain rhythm in this respect. He takes his breakfast, his midday meal, and his evening meal at certain times, and by doing so he follows, of course, a certain rhythm. But we know, alas, how it is with this rhythm in many another respect, through the humouring of the fastidiousness of many children who are simply given a thing whenever they crave it, regardless of all rhythm. Moreover, the fact that adults also are not very particular in observing a regular rhythm in connection with eating and drinking—there is not the slightest intention here of giving pedantic instruction in this matter, for our modern life does not always allow of rhythm—the fact that we fill ourselves with external nourishment with such irregularity, and that in our drinking especially we are so irregular, is sufficiently well known and need not be criticised but only mentioned. Yet, on the other hand, that which we supply to our organism with such imperfect rhythm must gradually be changed in rhythm so that it will adapt itself to the more regular rhythm of this organism, it must be adapted, as it were. The grossest irregularity must be removed, and something like the following must come about. Let us suppose that, in order to regulate his daily schedule, a man is compelled to breakfast at eight o'clock in the morning and to eat again at one or two o'clock and assume that this has become a habit. Now, suppose that he should go to see a friend, and that while there he should be invited, through a courtesy which cannot in general be too highly praised, to take something between these two meals. In this case he has interrupted his rhythm to a very decided extent, and thereby a certain positive influence is exerted upon the rhythm of his external organism.

Now there must be something able to strengthen correspondingly whatever is regular in rhythm in the supplying of external nourishment and to weaken the influence of whatever is irregularly introduced. The worst irregularities must be counterbalanced. Accordingly somewhere along the course taken by the food as it goes over into the rhythm of the blood, there must be inserted an organ that equalises the irregularity of the process of nourishment in contrast with the necessary regularity of the rhythm of the blood. This organ is the spleen. Thus, by observing certain very definite rhythmic processes brought about by the spleen we are able to get an idea of the fact that the spleen is really a “transformer.”1Figure taken from the electrical device which transforms the character of the current. It is there to counterbalance the irregularities in the digestive canal in order that they may become regularities in the circulation of the blood. For it would be fatal, especially in one's student days but also at other times, if certain irregularities in the taking of nutritive matter had necessarily to continue to the full extent of their action into the blood! There is much to be counterbalanced by means of a “backward thrust,” as we may call it; only so much is to be conducted over into the blood as is useful to it. This is the function of the spleen, that organ inserted in the blood-stream which so radiates its rhythm-bringing influence over the entire human organism as to produce the condition that has just been described. To external observation, all that we have obtained through the insight of an eye becoming inwardly clairvoyant is evident from the fact that the spleen does keep to a certain rhythm that actually reminds one, even if only slightly, of what I have just been stating. For it is extraordinarily difficult to find out the functions of the spleen by means of external physiological investigation. Outwardly, the only thing that shows itself is that the spleen is to a certain extent inflated for hours at a time after the partaking of a heavy meal; and that, if another meal does not follow, it contracts again.

Here you have a certain expanding and contracting of this organ. When it is realised that the human organism is not what it is often described as being, namely, a mere sum-total of the organs contained within it, but that all the organs send their most secret activities to all parts of the organism, one will then be able also to conceive how the rhythmic movements of the spleen, although dependent, of course, upon the outside world, that is, upon the supply of food, radiate throughout the whole organism and have a counterbalancing influence upon it. Now this is only one of the ways in which the spleen functions. It is impossible to explain all of them at once. Yet it would nevertheless, be extraordinarily interesting, since not everybody is capable of becoming clairvoyant, if such facts could be accepted by external physiology, accepted, let us say, as possible ideas, so that people would say: “I will for once imagine that what is attained by means of the inner clairvoyant eye is, after all, not such complete nonsense as it is often supposed to be. On the contrary, I shall neither believe nor disbelieve this; but I shall let it remain as an idea presented to me, and shall then investigate what external physiology can point out, whether, out of all that is asserted by occultists, anything whatever can be substantiated by showing clearly that it is actually confirmed by external observation.”2See in this connection Philo and physikalischer Nachweis der Wirksamkeit kleinster Entitäten. L. Kolisko. Orient-Occident Verlag, Stuttgart, Germany.

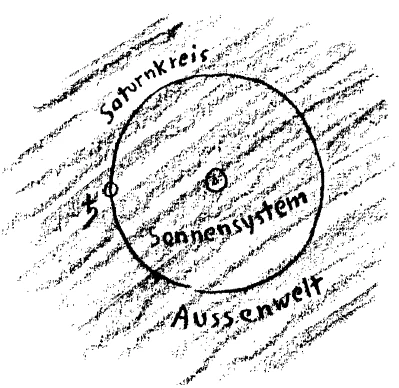

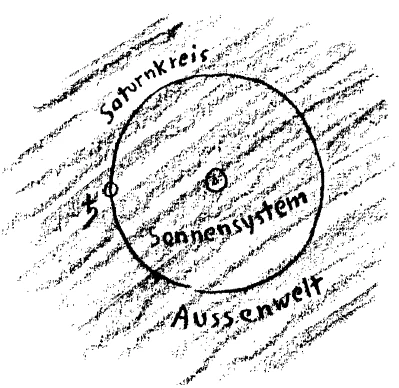

In a certain sense, what I have just said is such a confirmation. For it has become evident to us that the expansion and contraction of the spleen, due to the inner structure of the organ, have a certain regularity; but that, since these movements follow the eating of a meal, they are dependent also on the supply of external nourishment. Thus we have here in the spleen an organ which is dependent from the one aspect, that of the digestive canal, on external, human will; but from the other aspect, that of the blood, we have in it an organ that sets aside to a certain extent human choice, rejects it, and leads back to a rhythm, indeed, we might say, in this way really forms man in accordance with his being. For, if man is to be fashioned in accordance with his being, it is then especially necessary that the central instrument of that being, the blood, should be able to exercise its activity in the right way, in its own blood-rhythm. The human being, in so far as he is the carrier of his own blood-stream, must be set apart, so to speak, within himself, isolated from what proceeds with irregularity in the outside world, that outside world which he incorporates within himself when he takes in his nourishment out of it. Hence this is a process of isolation, a making the human being independent of the outside world. Every such individualising of any being, making it independent, is called in occultism saturnine, something brought about by the Saturn influence. This, as a matter of fact is the original idea associated with Saturn, that from an existing world some sort of Being is isolated, individualised, in such a way that within itself and of itself it can evolve regularity.

I shall for the present disregard the fact that the astronomy of our day reckons both Uranus and Neptune, which are outside the orbit of Saturn, as belonging to our solar system. For the occultist all those forces present in our entire solar system are, for the purpose of isolating them from the rest of the cosmos and individualising them, to be found in the Saturn forces—in that planet therefore, which is the most remote one belonging to this system. If, then, we visualise the entire solar system, we might say: The solar system must be so placed that it can follow its own laws within the orbit of encircling Saturn, and can make itself independent by tearing itself loose, as it were, from the surrounding world and from the formative forces of this surrounding world. For this reason occultists of all the ages have seen in the Saturn forces that which secludes our solar system within itself, thus making it possible for the solar system to develop a rhythm of its own which is not the same as the rhythm outside the world of our solar system.

In a certain way the spleen does something similar within our organism. Certainly we do not in this organism of ours have to do with a separating from the entire outside world, but only with a separating from this surrounding world in so far as it contains the nourishment for our organism and we ourselves introduce its activities into ourselves. The spleen is the organ we first meet when we do this, dealing, so to speak, with everything from outside in the same way as the Saturn forces deal with everything within our solar system, within the orbit of Saturn. The forces that are in the spleen isolate the circulation of our blood from all outside influences, and make of it a regular rhythm within itself, a system having its own rhythm.

Here we have already come nearer, although we are not yet really near as we shall see later, to those reasons, still more or less external, for which such names as the ones already mentioned are chosen in occultism. They are chosen because the occultist does not connect with the names borne by the planets merely what concerns the planets. When these names were originally created in the occult schools they were never applied merely to the separate planets; the name Saturn, for instance, was applied to anything that excluded a world outside from a system that took on a rhythmic form within itself. There is always a certain disadvantage for cosmic evolution, as a whole, when one system shuts itself off and regulates itself within itself, fashions a rhythm of its own. And the occultists have, consequently, been somewhat concerned about this disadvantage. We might say, indeed, that it is quite comprehensible that all activities in the entire universe have a basic inner relation and are mutually related. If any one “world,” be it a solar system, or be it the blood-system of the human being, is completely separated from the rest of the universe surrounding it, this signifies that it quite independently violates external laws, makes itself independent of them, changes itself and creates its own inner laws, its own rhythm. We shall see later how this may also be true in the case of the human being although it must be clear to us, in view of the whole discussion in to-day's lecture, that it is mostly a blessing that man maintains this inner Saturn-rhythm which the spleen has created for him. At the same time we shall see that we can apply this law also in the case of man, namely, that any being, whether it be a planet or a man, brings itself through seclusion within itself into a state of contradiction to the world around it. A contradiction is thus created between that which surrounds and that which is within the being concerned. This contradiction cannot be compensated for, after it has once appeared, until the inner rhythm set up has again adapted itself completely to the outer rhythm. We shall see that this applies also to the human being; for otherwise, according to what has been said, he would be compelled to adapt himself to irregularity. We shall find, however, that such is not the case. The inner rhythm, although it has established itself, must again strive after doing this to fashion itself in accordance with the entire outside world, which means that it must eliminate itself. Thus the being first comes to have an inner existence of its own; but, because it can now work independently, it aspires to adapt itself to the outside world and to become harmonious with it. To put it in other words, everything that has made itself independent as a result of a saturnine activity is doomed at the same time, because of this saturnine activity, to destroy itself again. Saturn, or Kronos, devours his own children, so the myth tells us. Here you see a deeply significant harmony between an occult idea, expressed in the name Kronos or Saturn, and a myth which expresses the same thing in a picture, a symbol: “Kronos devours his own children!”

We can try, at least, to let such things work upon us; and, if we allow them to do so in ever-increasing number, one new fact after another comes to light till it becomes impossible after a time to say, in the light and easy manner in which we so often hear a superficial solution proposed: “Here are some of these visionaries dreaming that the old myths and sagas contained the pictorial impress of a deeper wisdom!” If a man hears two or three, or let us say even ten, such “correspondences” presented, as these so often are presented in literature in a wholly superficial way, it is of course quite possible for him to oppose the idea that there is a deeper wisdom contained in the myths and sagas than in external science; that mythology leads us deeper into the foundations of things and of Being than do the methods of natural-scientific study. But if he allows such examples to work upon him again and again, and then becomes aware that, throughout the whole extent of the thought and feeling of men and of peoples, it is verified that in pictorial conceptions everywhere and always, over all parts of the earth, anyone with a very accurate observation and devoted interest in sagas and myths may find the metamorphoses of a deeper wisdom, then he will be able to understand why certain occultists can with justice say as they do: “He alone really comprehends the myths and sagas who has penetrated into human nature with the help of occult physiology.” And, indeed, more truly than is the case in external science do even the names in these myths and sagas and other traditions contain real physiology. When once people begin to fathom how much physiology was coined, for instance, in such names as Cain and Abel, and into the names of all their successors in those olden days when it was customary to coin an inner meaning into names, when they once see how much physiology, how much inner understanding for homely human wisdom is contained in those old names in a truly remarkable way, they will then win a tremendous respect and the deepest reverence for everything that has been devised in the course of the historical evolution of man for the purpose of enabling the soul, where it cannot as yet through its own wisdom ascend into the spiritual world, to have a conscious inner experience by means of pictures of its connection with these spiritual worlds. Then will be completely banished that idea which plays too large a part at the present time: “What splendid progress we men of to-day have made!” by which is often also meant: “How well we have succeeded in getting rid of those old pictorial expressions belonging to prehistoric ‘wisdom’!” We shall then cast away such feelings, and immerse ourselves with whole-hearted devotion in the course of human evolution throughout its successive epochs. For what the clairvoyant, with his opened inner eye, establishes physiologically as the inner nature of the human organs, is so expressed in these ancient pictures that the myths and sagas really contain in them the truth of the origin of man. To make possible the expression in pictures of this miraculous process, whereby external worlds have been compressed into human organs and have condensed and crystallised themselves in the course of infinitely long periods of time in order that they might become something which, in the form of a spleen for example, brings about an inner rhythm within us, or in the form of a liver or gall-bladder, etc., as we shall see tomorrow—to be able to express all this in pictures requires a divining of what we, by means of occult science, can re-establish from the human organisation. For what we find there has been born out of the worlds, as a microcosm out of the macrocosm. We look into this whole origin or beginning with the help of occult science on the one hand; and we see on the other that intimations of these beginnings are contained in the myths and sagas, and that those occultists are right who find a real meaning in them only when they are given a physiological foundation.

It is our purpose to-day at least to indicate these facts, if no more; for this can help us to win that reverence of which we spoke in our first hours together. If we practise such a method of study as this, quite apart now from the “pictures” belonging to the different peoples, by also directly pointing to what presents itself to a deeper investigation of the spiritual content of the human organs, if we are able to present this even only to a very limited extent, it will soon become clear to us what a miraculous structure this human organism is. In this series of lectures we shall endeavour to throw a little light upon the inner quality of being of this human organism.

Dritter Vortrag

Diese drei ersten Vorträge, einschließlich des heutigen, sind dazu bestimmt, uns im allgemeinen über das zu orientieren, was für das Leben, für die Wesenheit des Menschen in Betracht kommt. Daher werden in diesen ersten Vorträgen zunächst einige wichtige Begriffe gegeben werden, die ja sonst, weil die genaueren Ausführungen natürlich erst folgen sollen, ein bißchen in der Luft hängen würden. Es ist besser, wenn wir uns erst einen Überblick über die ganze Art aneignen, wie man den Menschen im okkulten Sinne zu betrachten hat, um dann in diese Betrachtung, die wir vorläufig als eine hypothetische hinnehmen, das hineinzubauen, was uns als die tieferen Gründe erscheinen kann.

Nun habe ich am Ende des gestrigen Vortrages bereits eines ausgeführt. Ich versuchte zu zeigen, daß der Mensch durch gewisse Seelenübungen, durch starke Gedanken- und Empfindungskonzentration eine andere Art seines Lebenszustandes hervorrufen kann, als es die gewöhnliche ist. Der gewöhnliche Lebenszustand drückt sich ja dadurch aus, daß wir im wachen Tagesleben eine enge Verbindung haben zwischen Nerven und Blut. Wenn wir uns schematisch ausdrücken wollen, können wir so sagen: Was durch die Nerven geschieht, schreibt sich ein in die Tafel des Blutes. Durch Seelenübungen bringt man es nun dahin, die Nerven so stark anzuspannen, daß deren Tätigkeit sich nicht mehr hineinerstreckt bis ins Blut, sondern daß diese Tätigkeit wie in den Nerv selber zurückgeworfen wird. Weilnun das Blut das Werkzeug unseres Ich ist, fühlt sich dann ein Mensch, welcher durch starke Empfindungs- und Gedankenkonzentration gleichsam sein Nervensystem freigemacht hat vom Blute, wie entfremdet seiner eigenen gewöhnlichen Wesenheit, wie herausgehoben aus ihr, er fühlt sich gleichsam ihr gegenüberstehend, so daß er zu dieser seiner gewöhnlichen Wesenheit nicht mehr sagen kann: das bin ich -, sondern sagen kann: das bist du. Er tritt also sich selbst so gegenüber wie einer fremden, in der physischen Welt lebenden Persönlichkeit. Wenn wir einmal ein wenig auf den Lebenszustand eines solchen, in einer gewissen Art hellsichtig gewordenen Menschen eingehen, so müssen wir sagen: Ein solcher fühlt sich so, wie wenn eine höhere Wesenheit in sein Seelenleben hineinragen würde. — Es ist dies ein ganz anderes Gefühl, als man es hat, wenn man im normalen Lebenszustand der Außenwelt gegenübersteht. Im gewöhnlichen Leben fühlt man sich den Dingen und Wesenheiten der äußeren Welt, Tieren, Pflanzen und so weiter, gegenüber fremd, man fühlt sich als ein Wesen neben ihnen oder außerhalb ihrer stehend. Man weiß ganz genau, wenn man eine Blume vor sich hat: Die Blume ist dort, und ich bin hier. - Anders ist das, wenn man auf die gekennzeichnete Art sich aus seinem subjektiven Ich heraushebt, wenn man durch Losreißen seines Nervensystems vom Blutsystem in die geistige Welt hinaufsteigt. Dann fühlt man nicht mehr: da ist das fremde Wesen, das uns gegenüberrtritt, und hier sind wir -, sondern dann ist es so, wie wenn das andere Wesen in uns eindringen würde und wir uns mit ihm eins fühlten. So darf man sagen: Der hellsichtig werdende Mensch beginnt bei fortgeschrittener Beobachtung die geistige Welt kennenzulernen, jene geistige Welt, mit der der Mensch in steter Verbindung steht und die ja auch im gewöhnlichen Leben durch unser Nervensystem auf dem Umwege durch die Sinneseindrücke zu uns kommt.

Diese geistige Welt also, von welcher der Mensch im normalen Bewußtseinszustand zunächst nichts weiß, ist es, die sich dann einschreibt in unsere Bluttafel und dadurch in unser individuelles Ich. Wir dürfen nämlich sagen: Alle dem, was uns äußerlich in der Sinneswelt umgibt, liegt eine geistige Welt zugrunde, die wir nur wie durch einen Schleier sehen, der durch die Sinneseindrücke gewoben wird. Im normalen Bewußtsein sehen wir diese geistige Welt nicht, über die der Horizont des individuellen Ich einen Schleier ausspannt. In dem Augenblick aber, wo wir von dem Ich frei werden, erlöschen auch die gewöhnlichen Sinneseindrücke, die haben wir dann nicht. Wir leben uns hinauf in eine geistige Welt, und das ist dieselbe geistige Welt, die eigentlich hinter den Sinneseindrücken ist, mit der wir eins werden, wenn wir unser Nervensystem herausheben aus unserem gewöhnlichen Blutorganismus.

Nun haben wir mit diesen Betrachtungen gewissermaßen das menschliche Leben verfolgt, wie es von außen angeregt wird und durch die Nerven auf das Blut wirkt. Wir haben aber schon gestern darauf aufmerksam gemacht, daß wir in dem rein organischen physischen Innenleben des Menschen eine Art zusammengedrückte Außenwelt sehen können, und wir haben namentlich darauf hingewiesen, wie eine Art in Organe zusammengedrängte Außenwelt vorhanden ist in unserer Leber, Galle und Milz. Wir können sagen: Wie das Blut nach der einen, der oberen Seite unseres Organismus das Gehirn durchläuft, um dort mit der Außenwelt in Berührung zu kommen — und das geschieht, indem auf das Gehirn die äußeren Sinneseindrücke wirken -—, so kommt das Blut, wenn es sich durch den Körper bewegt, in Beziehung zu den inneren Organen, von denen wir zunächst Leber, Galle und Milz betrachtet haben. Und daß in ihnen das Blut nicht mit irgendeiner Außenwelt in Berührung kommt, dafür sorgt die Tatsache, daß diese Organe sich nicht wie Sinnesorgane nach außen aufschließen, sondern in den Organismus eingeschlossen und von allen Seiten zugedeckt sind, so daß sie nur ein inneres Leben entfalten. Diese Organe können alle auch auf das Blut nur so wirken, wie sie selbst ihrer Eigenart nach sind. Leber, Galle und Milz bekommen nicht wie das Auge oder das Ohr äußere Eindrücke, können also auch nicht an das Blut Wirkungen weitergeben, welche von außen angeregt sind, sondern sie können in der Wirkung, welche sie auf das Blut haben, nur ihre eigene Natur zum Ausdruck bringen. Wenn wir also die innere Welt betrachten, in die die Außenwelt gleichsam wie zusammengedrängt ist, so können wir sagen: Hier wirkt eine verinnerlichte Außenwelt auf das menschliche Blut. Wenn wir uns das wieder schematisch zeichnen wollen, so können wir durch den schrägen Strich A-B (siehe Zeichnung Seite 50) die Tafel des Blutes angeben, durch die oberen Pfeile können wir alles das veranschaulichen, was von außen kommend an die Bluttafel herandringt, und durch die unteren Pfeile alles, was von innen kommend sich der Bluttafel einschreibt. Oder, wenn wir die Sache etwas weniger schematisch ansehen wollen, so können wir sagen: Wenn wir das menschliche Haupt und das hindurchgehende Blut betrachten, wie es beschrieben wird von außen durch die Sinnesorgane, so wirkt das Gehirn in seiner Arbeit in derselben Weise umwandelnd auf das Blut, wie die inneren Organe auf das Blut umwandelnd wirken. Denn diese drei Organe, Leber, Galle, Milz, wirken von der anderen Seite her auf das Blut, welches wir hier so zeichnen wollen, als ob es die Organe umflösse. So also würde das Blut gleichsam Strahlungen, Wirkungen empfangen können von den inneren Organen und würde damit sozusagen als Werkzeug des Ich in diesem Ich das innere Leben dieser Organe zum Ausdruck bringen, so wie in unserem Gehirnleben das zum Ausdruck kommt, was uns in der Welt umgibt.

Da müssen wir uns allerdings klar sein, daß noch etwas ganz Bestimmtes eintreten muß, damit diese Wirkungen der Organe auf das Blut möglich sind. Erinnern wir uns daran, daß wir sagten, daß in der Wechselwirkung von Nerv und Blutlauf überhaupt erst die Möglichkeit liegt, daß auf das Blut eine Wirkung ausgeübt, daß in das Blut sozusagen etwas eingeschrieben werden kann. Wenn von der Seite der inneren Organe her Wirkungen auf das Blut ausgeübt werden sollen, wenn gleichsam das innere Weltsystem des Menschen auf das Blut wirken soll, so muß zwischen diesen Organen und dem Blut etwas eingeschaltet sein wie ein Nervensystem. Es muß die innere Welt zuerst auf ein Nervensystem wirken können, um dann ihre Wirkungen auf das Blut übertragen zu können.

So sehen wir, einfach aus einem Vergleich des unteren Teiles des Menschen mit dem oberen, daß die Voraussetzung gemacht werden muß, daß zwischen unseren inneren Organen — als deren Repräsentanten wir diese drei Organe: Leber, Galle, Milz haben - und dem Blutkreislauf etwas eingeschaltet sein muß wie ein Nervensystem. Fragen wir die äußere Beobachtung, so zeigt sie uns in der Tat, daß in alle diese Organe das eingeschaltet ist, was wir das sympathische Nervensystem nennen, welches die Körperhöhle des Menschen ausfüllt und welches in einem analogen Verhältnisse zu der menschlichen Innenwelt und dem Blutkreislauf steht, wie andererseits das Rückenmark-Nervensystem zwischen der äußeren großen Welt und dem Blutumlauf des Menschen steht. Von diesem sympathischen Nervensystem, das ja zunächst längs des Rückgrates verläuft, dann, von dort ausgehend die verschiedensten Teile des Organismus durchzieht und sich ausbreitet, auch netzförmige Ausbreitungen zeigt, namentlich in der Bauchhöhle, wo man einen Teil dieses Systems populär auch das Sonnengeflecht nennt, von diesem sympathischen Nervensystem werden wir zu erwarten haben, daß es in einer gewissen Weise von dem anderen Nervensystem abweicht. Und es ist immerhin interessant — wenn es auch nicht zu einem Beweise dienen soll -, sich zu fragen: Wie könnte denn dieses Nervensystem gestaltet sein im Verhältnis zum Rückenmark-Nervensystem, wenn diese Bedingungen erfüllt würden, die wir jetzt hypothetisch gestellt haben? — Sie könnten einsehen: Wie sich das Rückenmark-Nervensystem öffnen muß dem Umkreis des Raumes, so muß dieses sympathische Nervensystem demjenigen zugeneigt sein, was zusammengedrängt ist in die innere Organisation. So verhält sich, wenn unseren Voraussetzungen entsprochen werden soll, das sympathische Nervensystem zu dem Rückenmark-Nervensystem etwa so, wie sich verhalten die Radien eines Kreises, die vom Mittelpunkt zur Peripherie gerichtet sind (siehe Zeichnung a), zu den sich von der Peripherie aus nach außen fortsetzenden Radien (b). Also in einer gewissen Weise müßte ein Gegensatz vorhanden sein zwischen dem sympathischen Nervensystem und zwischen dem Nervensystem des Gehirnes und Rückenmarkes. Dieser Gegensatz ist auch in der Wirklichkeit vorhanden. Und da sehen wir, wie schon darin vieles für uns liegen kann, daß wir imstande sind nachzuweisen: Wenn unsere Voraussetzungen richtig sind, dann muß die äußere Beobachtung sie in einer gewissen Weise bestätigen, und es zeigt sich, daß die äußere Beobachtung tatsächlich bestätigt, was wir als Voraussetzung gemacht haben. Während beim sympathischen Nervensystem im wesentlichen eine Art starke Nervenknoten vorhanden sind und die Ausstrahlungen dieser Nervenknoten, die verbindenden Fäden, verhältnismäßig dünn sind und wenig in Betracht kommen gegenüber den Nervenknoten, ist bei dem Gehirn-Rückenmark-Nervensystem gerade das Umgekehrte der Fall, da sind die verbindenden Fäden das Wesentliche, während die Nervenknoten nur eine untergeordnete Bedeutung haben. So bestätigt uns die Beobachtung in der Tat das, was wir als Voraussetzung annahmen. Wenn das sympathische Nervensystem die Aufgabe hat, die es nach dem, was wir gesagt haben, haben muß, dann muß sich das innere Leben unseres Organismus, das in der Durchnährung und Durchwärmung des Organismus zum Ausdruck kommt, gleichsam in dieses sympathische Nervensystem hineinergießen, und dieses Nervensystem müßte es auf die Bluttafel geradeso übertragen, wie die äußeren Eindrücke durch das Gehirn-Rückenmark-Nervensystem auf das Blut übertragen werden. So bekommen wir in das individuelle Ich hinein, durch das Instrument des Ich, das Blut — auf dem Umwege durch das sympathische Nervensystem -, die Eindrücke unseres eigenen körperlichen Inneren. Da aber unser körperliches Innere wie alles Physische aus dem Geiste heraus auferbaut ist, so bekommen wir das, was sich als geistige Welt zusammengedrängt hat in den entsprechenden Organen des inneren Menschen, herauf in unser [waches] Ich auf dem Umwege durch das sympathische Nervensystem.

So sehen wir auch hier, wie sich diese Zweiheit im Menschen noch genauer ausdrückt, von der wir in unseren Betrachtungen ausgegangen sind. Wir sehen die Welt einmal draußen, wir sehen sie einmal drinnen wirken; beide Male sehen wir diese Welt so wirken, daß zu dieser Wirkung einmal das eine, einmal das andere Nervensystem als Werkzeug dient. Wir sehen, wie in die Mitte zwischen Außenwelt und Innenwelt hineingestellt ist unser Blutsystem, das sich wie eine Tafel von zwei Seiten beschreiben läßt, einmal von außen, einmal von innen.

Nun haben wir gestern gesagt, und es heute der Deutlichkeit wegen wiederholt, daß der Mensch imstande ist, seine Nerven, insofern sie in die Sinneswelt hinausführen, sozusagen frei zu machen von den Wirkungen der Außenwelt auf das Blutsystem. Die Frage müssen wir uns nun vorlegen, ob auch nach der entgegengesetzten Richtung hin etwas Ähnliches möglich ist? Und wir werden später sehen, daß in der Tat auch solche Übungen der Seele möglich sind, welche dieselbe Wirkung, von der wir heute und gestern gesprochen haben, nach der anderen Richtung möglich machen. Jedoch besteht hier ein gewisser Unterschied. Während wir durch Gedankenkonzentration, durch Gefühlskonzentration, durch okkulte Übungen die Nerven unseres Gehirns und Rückenmarkes vom Blute losbekommen können, können wir durch solche Konzentrationen, welche gleichsam in unser Innenleben, in unsere Innenwelt hineingehen — und es sind dies namentlich diejenigen Konzentrationen, die man zusammenfassen kann unter dem Namen «mystisches Leben» -, so tief in uns eindringen, daß wir allerdings unser Ich dabei, also auch sein Werkzeug, das Blut, keineswegs unberücksichtigt lassen. Die mystische Versenkung, von der wir ja wissen — was später noch genauer ausgeführt werden soll-, daß der Mensch durch sie gleichsam untertaucht in seine eigene göttliche Wesenheit, in seine eigene Geistigkeit, insofern sie in ihm liegt, diese mystische Versenkung ist nicht zunächst ein Herausheben aus dem Ich. Sie ist im Gegenteil ein Sichhineinversenken in das Ich, eine Verstärkung, ein Energischermachen, eine Steigerung der IchEmpfindung. Davon können wir uns überzeugen, wenn wir — abgesehen von dem, was die Mystiker der Gegenwart sagen — uns ein wenig einlassen auf ältere Mystiker. Diese älteren Mystiker, gleichgültig, ob sie auf einem mehr oder weniger religiösen Boden stehen, sind vor allen Dingen bemüht, in ihr eigenes Ich hineinzudringen und abzusehen von alle dem, was die Außenwelt uns geben kann, um frei zu werden von allen äußeren Eindrücken und ganz in sich selber unterzutauchen. Diese innere Einkehr, dieses Untertauchen in das eigene Ich ist zunächst wie ein Zusammenziehen der ganzen Gewalt und Energie des Ich in den eigenen Organismus hinein. Das wirkt nun auf die ganze Organisation des Menschen weiter, und wir können sagen: Diese innere Versenkung, dieser im eigentlichen Sinne so zu nennende «mystische Weg» ist - im Gegensatz zu dem anderen Weg, den wir beschrieben haben — so, daß wir das Werkzeug des Ich, das Blut, nicht abziehen von dem Nerv, sondern es gerade mehr hinstoßen zum Nerv, zum sympathischen Nervensystem. Während wir also die Verbindung von Nerv und Blut lösen bei dem Vorgang, den wir gestern besprochen haben, machen wir im Gegensatz dazu durch die mystische Versenkung die Verbindung zwischen dem Blut und dem sympathischen Nervensystem stärker. Das ist das physiologische Gegenbild: Bei der mystischen Versenkung wird das Blut tiefer hineingedrängt zu dem sympathischen Nervensystem, während bei der anderen Art seelischer Übungen das Blut vom Nerv abgedrängt wird. Es ist also wie ein Eindrücken des Blutes in das sympathische Nervensystem, was in der mystischen Versenkung vor sich geht.

Nehmen wir nun an, wir könnten für eine Weile von dem absehen, daß der Mensch, wenn er in mystischer Versenkung in sein Inneres hineingeht, nicht loskommt von seinem Ich, sondern es im Gegenteil tiefer hineindrängt in sein Inneres und dabei alle schlechten, alle minder guten Eigenschaften, die er hat, mitnimmt. Wenn man sich in sein Inneres hineinversenkt, ist man sich zunächst nicht klar, daß man auch alle minder guten Eigenschaften hineindrückt in dieses Innere, mit anderen Worten, daß alles, was im leidenschaftlichen Blute ist, mit hineingeprägt wird in das sympathische Nervensystem. Aber nehmen wir an, wir könnten eine Weile davon absehen und uns sagen, der Mystiker habe Sorge getragen, bevor er zu einer solchen mystischen Versenkung gekommen ist, daß die minder guten Eigenschaften immer mehr und mehr verschwunden sind und daß anstelle der egoistischen Eigenschaften selbstlose, altruistische Gefühle getreten sind, er habe sich dadurch vorbereitet, daß er versuchte, das Gefühl des Mitleides mit allen Wesen in sich rege zu machen, um die Eigenschaften, die nur auf das Ich hinspekulieren, zu paralysieren durch selbstloses Mitgefühl für alle Wesen. Nehmen wir also an, der Mensch habe sich genügend sorgfältig vorbereitet, um sich in sein Inneres hinein zu versenken. Trägt der Mensch dann das Ich durch das Werkzeug seines Blutes in seine innere Welt hinein, dann kommt es dazu, daß dieses innere Nervensystem, das sympathische Nervensystem, von dem der Mensch im normalen Bewußtsein natürlich nichts weiß, hereinrückt in das Ich-Bewußtsein, daß er anfängt zu wissen: Du hast da in dir etwas, das dir ein Ähnliches von deiner inneren Welt vermitteln kann, wie dein Gehirn-Rückenmark-Nervensystem dir die äußere Welt vermittelt. - Man wird gewahr seines sympathischen Nervensystems, und wie man durch das GehirnRückenmark-Nervensystem die äußere Welt erkennen kann, so kommt einem jetzt entgegen die innere Welt. Aber wie wir bei den äußeren Eindrücken auch nicht die Nerven selbst sehen, sondern durch die Sehnerven die äußere Welt in unser Bewußtsein hereindringt, so dringen bei der mystischen Versenkung auch nicht die inneren Nerven ins Bewußtsein herein; der Mensch wird nur gewahr, daß er in ihnen ein Instrument hat, durch das er in das Innere schauen kann. Es tritt etwas ganz anderes ein, es tritt vor dem nach innen zu hellsichtig gewordenen menschlichen Erkenntnisvermögen die innere Welt auf. Wie uns der Blick nach außen die Außenwelt erschließt, und uns dabei nicht unsere Nerven zum Bewußtsein kommen, so kommt uns auch nicht unser sympathisches Nervensystem zum Bewußtsein, wohl aber das, was sich uns als Innenwelt entgegenstellt. Nur müssen wir sehen, daß diese Innenwelt, die uns da zum Bewußtsein kommt, eigentlich wir selbst als physischer Mensch sind.

Vielleicht liegt es nicht besonders nahe, aber ich möchte doch sagen: Einem ein klein wenig materialistischen Denker könnte eine Art von Horror aufsteigen, wenn er sich sagen sollte, daß er seinen eigenen Organismus von innen sehen kann, und er könnte vielleicht meinen: Da sehe ich aber auch etwas Rechtes, wenn ich durch mein sympathisches Nervensystem hellsichtig werde und meine Leber, Galle und Milz zu sehen bekomme! — Ich meine, es muß ja nicht besonders naheliegen, aber man könnte es sich doch sagen. So ist die Sache aber nicht. Denn bei einem solchen Einwand würde man nicht berücksichtigen, daß der Mensch im gewöhnlichen Leben seine Leber, Galle und Milz und so weiter von außen anschaut wie die anderen äußeren Gegenstände auch. So wie Sie in der Anatomie, in der gewöhnlichen Physiologie Leber, Galle, Milz und so weiter kennenlernen, wenn Sie einen Menschen aufschneiden, sind diese Organe natürlich durch die äußeren Sinne, durch das Gehirn-Rükkenmark-Nervensystem angeschaut, geradeso wie irgend etwas anderes. Aber in einer ganz anderen Lage ist der Mensch, wenn er versucht, sein sympathisches Nervensystem zu gebrauchen, um nach innen hellsichtig zu werden. Da sieht er keineswegs dasselbe, was er von außen sehen kann, sondern da sieht er das, um dessentwillen die Hellseher aller Zeiten so sonderbare Namen für diese Organe gewählt haben, wie ich sie Ihnen im zweiten Vortrage angeführt habe.

Da wird er nämlich gewahr, daß in der Tat dem äußeren Anschauen durch das Gehirn-Rückenmark-Nervensystem diese Organe als Maja, in äußerer Illusion erscheinen in dem Anblick, den sie nach außen bieten, nicht in ihrer inneren wesenhaften Bedeutung. Man sieht in der Tat etwas ganz anderes, wenn man mit dem nach innen gewendeten Auge diese seine innere Welt hellseherisch belauschen kann. Da wird man nach und nach gewahr, warum die Hellseher aller Zeiten einen Zusammenhang der Organe mit den Wirkungen der Planeten gesehen haben. Wie wir gestern gesagt haben, wurde die Milzwirkung mit dem Namen des Saturn, die Leberwirkung mit dem Jupiter und die Gallewirkung mit dem Mars in Zusammenhang gebracht. Denn was man im eigenen Inneren sicht, das ist in der Tat grundverschieden von dem, was sich dem äußeren Anblick darbietet. Da wird man gewahr, daß man wirklich in den inneren Organen umgrenzte, zusammengeschlossene Partien der Außenwelt vor sich hat. Vor allem wird eines klar, was uns zunächst als ein Beispiel dienen soll: Durch diese Art zu einer Erkenntnis zu kommen, die über das gewöhnliche Anschauen hinausführt, können wir uns davon überzeugen, daß die menschliche Milz ein sehr bedeutungsvolles Organ ist. Dieses Organ erscheint ja der inneren Betrachtung wirklich so, als wenn es nicht aus äußerer Substanz, aus fleischlicher Materie bestehen würde, sondern — wenn der Ausdruck gestattet ist, obwohl er nur annähernd das wiedergeben kann, was gesehen wird die Milz erscheint tatsächlich wie ein leuchtender Weltenkörper im kleinen mit allem möglichen inneren Leben, das sehr kompliziert ist. Ich habe Sie gestern darauf aufmerksam gemacht, daß die Milz, äußerlich betrachtet, beschrieben werden kann als ein blutreiches Gewebe, eingebettet darin die erwähnten weißen Körperchen. So daß man von einer äußeren physiologischen Betrachtung ausgehend sagen kann, daß das Blut, welches sich durch die Milz ergießt, durch sie wie durch ein Sieb durchgesiebt wird. Der inneren Betrachtung aber stellt sich die Milz dar als ein Organ, das durch mannigfache innere Kräfte in eine beständige rhythmische Bewegung gebracht wird. Wir überzeugen uns schon bei einem solchen Organ davon, daß im Grunde genommen in der Welt ungeheuer viel auf Rhythmus ankommt. Eine Ahnung von der Bedeutung des Rhythmus im Gesamtleben der Welt können wir ja bekommen, wenn wir den äußeren Rhythmus des Kosmos wiedererkennen im Blut-Pulsschlag. Auch äußerlich können wir den Rhythmus in den Organen, auch in dem Organ der Milz, ziemlich genau verfolgen. Für den, der mit nach innen gewendetem hellseherischen Blick die Organe anschaut, dem offenbaren sich die Differenzierungen der Milz wie in einem Lichtkörper, sie sind dazu da, um der Milz einen gewissen Rhythmus im Leben zu geben. Dieser Rhythmus unterscheidet sich von anderen Rhythmen, die wir sonst gewahr werden, ganz beträchtlich. Und gerade bei der Milz ist es interessant zu studieren, wie sich dieser Rhythmus der Milz ganz beträchtlich unterscheidet von jedem anderen Rhythmus; er ist nämlich weit weniger regelmäßig als andere Rhythmen. Warum? Dies ist aus dem Grunde der Fall, weil die Milz in einer gewissen Weise naheliegt dem menschlichen Ernährungsapparat und mit demselben etwas zu tun hat. Das werden Sie gleich verstehen, wenn wir ein wenig darauf Rücksicht nehmen, wie ungeheuer regelmäßig beim Menschen der Rhythmus des Blutes sein muß, damit das Leben in einer richtigen Weise aufrechterhalten werden kann. Das muß ein sehr regelmäßiger Rhythmus sein. Aber es gibt einen anderen Rhythmus, und der ist nur in geringem Maße regelmäßig, obwohl von ihm zu wünschen wäre, daß er durch die Selbsterziehung der Menschen immer regelmäßiger und regelmäßiger würde, namentlich in dem kindlichen Lebensalter: das ist der Rhythmus, in dem wir uns ernähren, der Rhythmus von Essen und Trinken. Einen gewissen Rhythmus hält darin ja wohl ein einigermaßen ordentlicher Mensch ein; er nimmt zu bestimmten Zeiten seine Tagesmahlzeiten, das Frühstück, das Mittagessen und das NachtmaHl ein, so daß er dadurch doch einen gewissen Rhythmus hat. Aber wie ist es mit diesem Rhythmus eigentlich bestellt? In vieler Hinsicht — das ist ja traurig bekannt — wird diese Regelmäßigkeit durchbrochen durch das Entgegenkommen vieler Eltern gegenüber der Genäschigkeit ihrer Kinder, denen man einfach dann etwas gibt, wenn sie gerade danach Verlangen haben, wobei abgesehen wird von allem Rhythmus. Und auch die Erwachsenen sind nicht gerade so ungeheuer darauf aus, immer einen genauen Rhythmus in bezug auf Essen und Trinken einzuhalten. Das soll gar nicht in pedantischer oder moralisierender Weise gemeint sein, denn das moderne Leben macht das nicht immer möglich. Wie unregelmäßig die Nahrung in den Menschen hineingestopft wird, wie unregelmäßig namentlich getrunken wird, das ist ja hinlänglich bekannt und soll nicht getadelt, sondern nur erwähnt werden. Es muß aber das, was wir in einer mangelhaften rhythmischen Art unserem Organismus zuführen, allmählich so umrhythmisiert werden, daß es sich in den regelmäßigeren Rhythmus des Organismus einfügt; es muß so umgeschaltet werden, daß wenigstens die gröbsten Unregelmäßigkeiten in der Nahrungsaufnahme beseitigt werden. Nehmen wir an, ein Mensch sei durch seinen Beruf gezwungen, um acht Uhr morgens zu frühstücken und um ein oder zwei Uhr zu Mittag zu essen, und diese regelmäßige Tageseinteilung sei ihm eine Gewohnheit. Nun nehmen wir weiter an, er würde zu einem guten Freunde gehen, und da gebiete es ihm die sonst ja nicht genug zu lobende Höflichkeit, zwischen diesen beiden Mahlzeiten eine Erfrischung zu sich zu nehmen. Damit hat er den gewohnten Rhythmus seiner Nahrungsaufnahme in einer ganz erheblichen Weise durchbrochen, und dadurch wird auf den Rhythmus seines Organismus eine ganz bestimmte Wirkung ausgeübt. Es muß nun etwas da sein im Organismus, das in entsprechender Weise dasjenige stärker macht, was regelmäßig im Rhythmus ist und was die Wirkung dessen abschwächen muß, was unregelmäßig ist. Es müssen die gröbsten Unregelmäßigkeiten ausgeglichen werden, so daß beim Übergehen der Nahrungsmittel auf das Blutsystem ein Organ eingeschaltet sein muß, das die Unregelmäßigkeit des Ernährungsrhythmus ausgleicht gegenüber der notwendigen Regelmäßigkeit des Blutrhythmus. Und dieses Organ ist die Milz. So können wir an ganz bestimmten rhythmischen Vorgängen, wie es jetzt charakterisiert worden ist, einen Begriff dafür erhalten, daß die Milz ein Umschalter ist, um Unregelmäßigkeiten im Verdauungskanal so auszugleichen, daß sie zu Regelmäßigkeiten werden in der Blutzirkulation. Denn es wäre in der Tat eine ganz fatale Sache, wenn gewisse Unregelmäßigkeiten in dem Aufnehmen von Nahrungsstoffen - namentlich in der Studentenzeit oder auch zu anderen Zeiten - ihre ganze Wirkung fortsetzen müßten in das Blut hinein. Da ist viel auszugleichen, und es ist nur so viel auf das Blut überzuleiten, als diesem zuträglich ist. Diese Aufgabe hat das in die Blutbahn eingeschaltete Milzorgan, das seine rhythmisierende Wirkung so ausstrahlt über den ganzen menschlichen Organismus, daß das zustande kommt, was Jetzt beschrieben worden ist.

Was wir jetzt hervorgeholt haben aus dem Einblick des hellsehend gewordenen Auges, zeigt sich auch der äußeren Beobachtung, nämlich daß die Milz einen gewissen Rhythmus einhält. Es ist außerordentlich schwierig, durch die äußeren physiologischen Untersuchungen allein diese Aufgabe der Milz herauszufinden, man kann aber durch äußerliche Beobachtung feststellen, daß die Milz gewisse Stunden hindurch nach einer reichlich genossenen Mahlzeit angeschwollen ist und daß sie, wenn nicht wieder nachgeschoben wird, sich wieder zusammenzieht, wenn eine angemessene Zeit vergangen ist. Durch eine gewisse Ausdehnung und Zusammenziehung dieses Organs wird die Unregelmäßigkeit in der Nahrungsaufnahme auf den Rhythmus des Blutes umgeschaltet. Und wenn Sie sich dessen bewußt sind, daß der menschliche Organismus nicht bloß das ist, als was man ihn oft beschreibt, nämlich eine Summe seiner Organe, sondern daß alle Organe ihre geheimen Wirkungen nach allen Teilen des Organismus hinschicken, so werden Sie sich auch vorstellen können, daß die rhythmische Tätigkeit der Milz von der Außenwelt, nämlich von der Zuführung der Nahrungsmittel abhängt, und daß diese rhythmischen Bewegungen der Milz ausstrahlen in den ganzen Organismus und über den ganzen Organismus hin ausgleichend wirken können. Das ist zwar nur eine Art, wie die Milz wirkt; denn es ist unmöglich, alle Arten gleich anzuführen.

Es wäre nun in der Tat außerordentlich interessant zu sehen, ob die äußere Physiologie solche Dinge, wie sie eben ausgesprochen wurden, bestätigen würde, wenn sie dieselben — da ja nicht alle Menschen gleich hellsehend werden können — hinnehmen würde, ich möchte sagen, wie eine «hingeworfene Idee», wenn also zunächst gesagt würde: Ich will mir einmal vorstellen, daß es doch nicht so ganz verdrehtes Zeug ist, was die Okkultisten sagen, ich will es einmal weder glauben noch nicht glauben, sondern es als Idee dahingestellt sein lassen und prüfen, ob sich davon irgend etwas durch die äußere Physiologie beweisen läßt. - Dann könnten Untersuchungen der äußeren Physiologie angestellt werden, die den Beweis erbringen könnten für das, was aus hellseherischer Beobachtung heraus gewonnen wurde.

Eine solche Bestätigung haben wir ja schon genannt, das Ausdehnen und Zusammenziehen der Milz. Es zeigt sich, weil die Ausdehnung der Milz auf die Einnahme einer Mahlzeit folgt, daß sie von der Nahrungsaufnahme abhängig ist. So haben wir in der Milz ein Organ gefunden, das nach der einen Seite hin von menschlicher Willkür abhängig ist, auf der anderen Seite, nach der Blutseite hin, die Unregelmäßigkeiten der menschlichen Willkür beseitigt, sie ablähmt, das heißt sie umschaltet auf den Rhythmus des Blutes, und dadurch das Physische des Menschen sozusagen erst seiner Wesenheit gemäß gestaltet werden kann. Denn soll der Mensch seiner Wesenheit gemäß gestaltet sein, dann muß ja namentlich das Mittelpunktswerkzeug seiner Wesenheit, das Blut, in der richtigen Weise seine Wirkung ausüben können, in dem eigenen Blutrhythmus. Es muß der Mensch, insofern er Träger seines Blutkreislaufes ist, in sich abgesondert, isoliert sein von dem, was draußen in der Außenwelt unregelmäßig vorgeht, und von dem, was auf den Menschen dadurch einwirkt, daß er völlig unrhythmisch sich seine Nahrung einverleibt.

Es ist also ein Isolieren, ein Unabhängigmachen der menschlichen Wesenheit von der Außenwelt. Jedes solches Individualisieren, Selbständigmachen einer Wesenheit nennt man im Okkultismus «Saturnisch», etwas, das durch Saturnwirkung herbeigeführt wird. Das ist die ursprüngliche Idee, das Wesentliche des Saturnischen: daß aus einem umfassenden Gesamtorganismus ein Wesen herausgestellt, isoliert, individualisiert wird, so daß es in sich selber eine gesonderte Regelmäßigkeit entfalten kann. Ich will jetzt davon absehen, daß ja von unserer heutigen Astronomie außerhalb der Saturnbahn noch Uranus und Neptun zu unserem Sonnensystem gerechnet werden. Für den Okkultisten ist alles das, was an Kräften vorhanden ist, um unser Sonnensystem aus der übrigen Welt herauszuheben, abzusondern, zu isolieren und zu individualisieren, ihm eine Eigengesetzlichkeit zu geben, in den Saturnkräften gegeben.

Alle diese Kräfte sind in dem gegeben, was in unserem Sonnensystem der äußerste Planet ist. Wenn man sich die Welt vorstellt, könnte man sagen, daß innerhalb der Kreisbahn des Saturns das Sonnensystem so darinnen ist, daß es innerhalb dieser Bahn seinen eigenen Gesetzen folgen kann und sich unabhängig machen kann, indem es sich herausreißt aus der Umwelt und den gestaltenden Kräften der Umwelt. Aus diesem Grunde sahen die Okkultisten aller Zeiten in den saturnhaften Kräften das, was unser Sonnensystem in sich selber abschließt, was es dem Sonnensystem möglich macht, einen eigenen Rhythmus zu entfalten, der nicht derselbe ist wie der Rhythmus draußen, der außerhalb der Welt unseres Sonnensystems herrscht.

Etwas Ähnlichem begegnen wir in unserem Organismus bei der Milz. In unserem Organismus haben wir es zwar nicht zu tun mit einem Absondern gegen die ganze äußere Welt, sondern nur von einer Umwelt, insofern sie die Nahrungsmittel für unseren Organismus enthält. In der Milz haben wir dasjenige Organ im Körper zu sehen, das alles, was von draußen kommt, so behandelt, wie das innerhalb der Saturnbahn des Sonnensystems Liegende von den Saturnkräften behandelt wird: daß es zuerst umrhythmisiert wird in den Rhythmus und die Gesetzmäßigkeit des Menschen. Was durch die Milz geschieht, das isoliert unseren Blutkreislauf von allen äußeren Wirkungen, das macht ihn zu einem in sich selber regelmäßigen System, das seinen eigenen Rhythmus haben kann.

Damit kommen wir schon den Gründen etwas näher, die im Okkultismus für die Wahl von Planetennamen für die Organe maßgebend waren. In den okkulten Schulen wurden diese Namen ursprünglich nicht bloß auf die einzelnen physisch sichtbaren Planeten angewendet. Der Name «Saturn» zum Beispiel wurde ja, wie schon gesagt, auf alles angewendet, was bewirkt, daß sich etwas aus einer größeren Gesamtheit aussondert und sich abschließt zu einem System, das in sich selber rhythmisch gestaltet ist. Daß ein System sich abschließt und sich in sich selbständig rhythmisch gestaltet, hat einen gewissen Nachteil für die gesamte Weltentwickelung, und das hat immer die Okkultisten ein wenig bekümmert. Es ist ja leicht verständlich, daß in der kleinen und in der großen Welt alle Wirkungen zueinander in Beziehungen stehen, daß alle sich aufeinander beziehen. Wenn nun irgend etwas, sei es ein Sonnensystem, sei es das Blutsystem des Menschen, sich herausgliedert aus der ganzen Umwelt und einer Eigengesetzmäßigkeit folgt, so bedeutet das, daß ein solches System die äußeren umfassenden Gesetze durchbricht, verletzt, daß es sich verselbständigt gegenüber den äußeren Gesetzen und sich eigene innere Gesetze und einen eigenen Rhythmus schafft, welche denen der Umwelt zunächst widersprechen. Wir werden sehen, wie das auch auf den physischen Menschen bezogen werden kann, obwohl es uns nach den ganzen Auseinandersetzungen des heutigen Vortrages klar sein muß, daß es zunächst für den Menschen segensreich ist, daß er diesen durch das Saturnische der Milz geschaffenen inneren Rhythmus erhalten hat. Aber wir werden doch sehen, daß ein Wesen, sei es ein Planet, sei es ein Mensch, durch das Sichabschließen in sich selber sich in einen Widerspruch bringt zur umliegenden Welt. Es ist ein Widerspruch geschaffen zwischen dem, was um uns ist, und dem, was in uns ist. Dieser Widerspruch, der nun einmal vorhanden ist, kann nicht früher ausgeglichen werden, als bis sich der im Inneren hergestellte Rhythmus dem äußeren Rhythmus wieder völlig angepaßt hat. Wir werden noch sehen, wie dies auch auf den physischen Menschen bezogen wird; denn so, wie es jetzt gesagt worden ist, sieht es aus, als ob der Mensch sich anpassen müßte an die Unregelmäßigkeit. Wir werden aber sehen, daß es anders ist. Der innere Rhythmus muß, nachdem er sich hergestellt hat, danach streben, sich wiederum mit der ganzen äußeren Welt gleich zu gestalten, das heißt, sich selber aufzuheben. Das heißt also: Die Wesenheit, die im Inneren entsteht und selbständig arbeitet, muß das Bestreben haben, sich wiederum an die Außenwelt anzupassen und dieser Außenwelt gegenüber so zu werden, wie diese selber ist. Mit anderen Worten: Alles, was durch eine saturnische Wirkung verselbständigt wird, das wird zugleich durch diese saturnische Wirkung dazu verurteilt, sich selber wieder zu zerstören. Der Mythos drückt das im Bilde aus: Saturn — oder Kronos — verzehrt seine eigenen Kinder.