Human and Cosmic Thought

GA 151

21 January 1913, Berlin

Lecture II

The study of Spiritual Science should always go hand in hand with practical experience of how the mind works. It is impossible to get entirely clear about many things that we discussed in the last lecture unless one tries to get a kind of living grasp of what thinking involves in terms of actualities. For why is it that among the very persons whose profession it is to think about such questions, confusion reigns, for example, as to the relation between the general concept of the “triangle-in-general” and specific concepts of individual triangles? How is it that people puzzle for centuries over questions such as that of the hundred possible and the hundred real thalers cited by Kant? Why is it that people fail to pursue the very simple reflections that are necessary to see that there cannot really be any such thing as a “pragmatic” account of history, according to which the course of events always follows directly from preceding events? Why do people not reflect in such a way that they would be repelled by this impossible mode of regarding the history of man, so widely current nowadays? What is the cause of all these things?

The reason is that far too little trouble is taken over learning to handle with precision the activities of thinking, even by people whose business this should be. Nowadays everyone wants to feel that he has a perfect claim to say: “Think? Well, one can obviously do that.” So they begin to think. Thus we have various conceptions of the world; there have been many philosophers—a great many. We find that one philosopher is after this and another is after that, and that many fairly clever people have drawn attention to many things. If someone comes upon contradictions in these findings, he does not ponder over them, but he is quite pleased with himself, fancying that now he can “think” indeed. He can think again what those other fellows have thought out, and feels quite sure that he will find the right answer himself. For no one nowadays must make any concession to authority! That would deny the dignity of human nature! Everyone must think for himself. That is the prevailing notion in the realm of thought.

I do not know if people have reflected that this is not their attitude in other realms of life. No one feels committed to belief in authority or to a craving for authority when he has his coat made at the tailor's or his shoes at the shoemaker's. He does not say: “It would be beneath the dignity of man to let one's things be made by persons who are known to be thoroughly acquainted with their business.” He may perhaps even allow that it is necessary to learn these skills. But in practical life, with regard to thinking, it is not agreed that one must get one's conceptions of the world from quarters where thinking and much else has been learnt. Only rarely would this be conceded to-day.

This is one tendency that dominates our life in the widest circles, and is the immediate reason why human thinking is not a very widespread product nowadays. I believe this can be quite easily grasped. For let us suppose that one day everybody were to say: “What!—learn to make boots? For a long time that has been unworthy of man; we can all make boots.” I don't know if only good boots would come from it. At all events, with regard to the coining of correct thoughts in their conception of the world, it is from this sort of reasoning that men mostly take their start at the present day. This is what gives its deeper meaning to my remark of yesterday—that although thought is something a man is completely within, so that he can contemplate it in its inner being, actual thinking is not as common as one might suppose. Besides this, there is to-day a quite special pretension which could gradually go so far as to throw a veil over all clear thinking. We must pay attention to this also; at least we must glance at it.

Let us suppose the following. There was once in Görlitz a shoemaker named Jacob Boehme. He had learnt his craft well—how soles are cut, how the shoe is formed over the last, and how the nails are driven into the soles and leather. He knew all this down to the ground. Now supposing that this shoemaker, by name Jacob Boehme, had gone around and said: “I will now see how the world is constructed. I will suppose that there is a great last at the foundation of the world. Over this last the world-leather was once stretched; then the world-nails were added, and by means of them the world-sole was fastened to the world-upper. Then boot-blacking was brought into play, and the whole world-shoe was polished. In this way I can quite clearly explain to myself how in the morning it is bright, for then the shoe-polish of the world is shining, but in the evening it is soiled with all sorts of things; it shines no longer. Hence I imagine that every night someone has the duty of repolishing the world-boot. And thus arises the difference between day and night.” Let us suppose that Jacob Boehme had said this.

Yes, you laugh, for of course Jacob Boehme did not say this; but still he made good shoes for the people of Görlitz, and for that he employed his knowledge of shoe-making. But he also developed his grand thoughts, through which he wanted to build up a conception of the world; and for that he resorted to something else. He said to himself: My shoe-making is not enough for that; I dare not apply to the structure of the world the thoughts I put into making shoes. And in due course he arrived at his sublime thoughts about the world. Thus there was no such Jacob Boehme as the hypothetical figure I first sketched, but there was another one who knew how to set about things. But the hypothetical “Jacob Boehmes”, like the one you laughed over—they exist everywhere to-day.

For example, we find among them physicists and chemists who have learnt the laws governing the combination and separation of substances; there are zoologists who have learnt how one examines and describes animals; there are doctors who have learnt how to treat the physical human body, and what they themselves call the soul. What do they all do? They say: When a person wants to work out for himself a conception of the world, then he takes the laws that are learnt in chemistry, in physics, or in physiology—no others are admissible—and out of these he builds a conception of the world for himself. These people proceed exactly as the hypothetical shoemaker would have done if he had constructed the world-boot, only they do not notice that their world-conceptions come into existence by the very same method that produced the hypothetical world-boot. It does certainly seem rather grotesque if one imagines that the difference between day and night comes about through the soiling of shoe-leather and the repolishing of it in the night. But in terms of true logic it is in principle just the same if an attempt is made to build a world out of the laws of chemistry, physics, biology and physiology. Exactly the same principle! It is an immense presumption on the part of the physicist, the chemist, the physiologist, or the biologist, who do not wish to be anything else than physicist, chemist, physiologist, biologist, and yet want to have an opinion about the whole world. The point is that one should go to the root of things and not shirk the task of illuminating anything that is not so clear by tracing it back to its true place in the scheme of things. If you look at all this with method and logic, you will not need to be astonished that so many present-day conceptions of the world yield nothing but the “world-boot”. And this is something that can point us to the study of Spiritual Science and to the pursuit of practical trains of thought; something that can urge us to examine the question of how we must think in order to see where shortcomings exist in the world.

There is something else I should like to mention in order to show where lies the root of countless misunderstandings with regard to the ideas people have about the world. When one concerns oneself with world-conceptions, does one not have over and over again the experience that someone thinks this and someone else that; one man upholds a certain view with many good reasons (one can find good reasons for everything), while another has equally good reasons for his view; the first man contradicts his opponent with just as good reasons as those with which the opponent contradicts him. Sects arise in the world not, in the first place, because one person or another is convinced about the right path by what is taught here or there. Only look at the paths which the disciples of great men have had to follow in order to come to this or that great man, and then you will see that herein lies something important for us with regard to karma. But if we examine the outlooks that exist in the world to-day, we must say that whether someone is a follower of Bergson, or of Haeckel, or of this or that (karma, as I have already said, does not recognise the current world-conception) depends on other things than on deep conviction. There is contention on all sides!

Yesterday I said that once there were Nominalists, persons who maintained that general concepts had no reality, but were merely names. These Nominalists had opponents who were called Realists (the word had a different meaning then). The Realists maintained that general concepts are not mere words, but refer to quite definite realities. In the Middle Ages the question of Realism versus Nominalism was always a burning one, especially for theology, a sphere of thought with which present-day thinkers trouble themselves very little. For in the time when the question of Nominalism versus Realism arose (from the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries) there was something that belonged to the most important confessions of faith, the question about the three “Divine Persons”—Father, Son and Holy Ghost—who form One Divine Being, but are still Three real Persons. The Nominalists maintained that these three Divine Persons existed only individually, the “Father” for Himself, the “Son” for Himself, and the “Holy Ghost” for Himself; and if one spoke of a “Collective God” Who comprised these Three, that was only a name for the Three. Thus Nominalism did away with the unity of the Trinity. In opposition to the Realists, the Nominalists not only explained away the unity, but even regarded it as heretical to declare, as the Realists did, that the Three Persons formed not merely an imaginary unity, but an actual one.

Thus Nominalism and Realism were opposites. And anyone who goes deeply into the literature of Realism and Nominalism during these centuries gets a deep insight into what human acumen can produce. For the most ingenious grounds were brought forward for Nominalism, just as much as for Realism. In those days it was more difficult to be reckoned as a thinker because there was no printing press, and it was not an easy thing to take part in such controversies as that between Nominalism and Realism. Anyone who ventured into this field had to be better prepared, according to the ideas of those times, than is required of people who engage in controversies nowadays. An immense amount of penetration was necessary in order to plead the cause of Realism, and it was equally so with Nominalism. How does this come about? It is grievous that things are so, and if one reflects more deeply on it, one is led to say: What use is it that you are so clever? You can be clever and plead the cause of Nominalism, and you can be just as clever and contradict Nominalism. One can get quite confused about the whole question of intelligence! It is distressing even to listen to what such characterisations are supposed to mean.

Now, as a contrast to what we have been saying, we will bring forward something that is perhaps not nearly so discerning as much that has been advanced with regard to Nominalism or to Realism, but it has perhaps one merit—it goes straight to the point and indicates the direction in which one needs to think.

Let us imagine the way in which one forms general concepts; the way in which one synthesizes a mass of details. We can do this in two ways: first as a man does in the course of his life through the world. He sees numerous examples of a certain kind of animal: they are silky or woolly, are of various colours, have whiskers, at certain times they go through movements that recall human “washing”, they eat mice, etc. One can call such creatures “cats”. Then one has formed a general concept. All these creatures have something to do with what we call “cats”. But now let us suppose that someone has had a long life, in the course of which he has encountered many cat-owners, men and women, and he has noticed that a great many of these people call their pets “Pussy”. Hence he classes all these creatures under the name of “Pussy”. Hence we now have the general concept “Cats” and the general concept “Pussy”, and a large number of individual creatures belonging in both cases to the general concept. And yet no one will maintain that the general concept “Pussy” has the same significance as the general concept “Cats”. Here the real difference comes out. In forming the general concept “Pussy” which is only a summary of names that must rank as individual names, we have taken the line, and rightly so, of Nominalism; and in forming the general concept “Cats” we have taken the line of Realism, and rightly so. In one case Nominalism is correct; in the other. Realism. Both are right. One must only apply these methods within their proper limits. And when both are right, it is not surprising that good reasons for both can be adduced. In taking the name “Pussy”, I have employed a somewhat grotesque example. But I can show you a much more significant example and I will do so at once.

Within the scope of our objective experience there is a whole realm where Nominalism—the idea that the collective term is only a name—is fully justified. We have “one”, “two”, “three”, “four”, “five”, and so on, but it is impossible to find in the expression “number” anything that has a real existence. “Number” has no existence. “One”, “two”, “three”, “five”, “six”,—they exist. But what I said in the last lecture, that in order to find the general concept one must let that which corresponds to it pass over into movement—this cannot be done with the concept “Number”. One “one” does not pass over into “two”. It must always be taken as “one”. Not even in thought can we pass over into two, or from two into three. Only the individual numbers exist, not “number” in general. As applied to the nature of numbers, Nominalism is entirely correct; but when we come to the single animal in relation to its genus, Realism is entirely correct. For it is impossible for a deer to exist, and another deer, and yet another, without there being the genus “deer”. The figure “two” can exist for itself, “one”, “seven”, etc., can exist for themselves. But in so far as anything real appears in number, the number is a quality, and the concept “number” has no specific existence. External things are related to general concepts in two different ways: Nominalism is appropriate in one case, and Realism in the other.

On these lines, if we simply give our thoughts the right direction, we begin to understand why there are so many disputes about conceptions of the world. People generally are not inclined, when they have grasped one standpoint, to grasp another as well. When in some realm of thought somebody has got hold of the idea “general concepts have no existence”, he proceeds to extend to it the whole make-up of the world. This sentence, “general concepts have no existence” is not false, for when applied to the particular realm which the person in question has considered, it is correct. It is only the universalising of it that is wrong. Thus it is essential, if one wants to form a correct idea of what thinking is, to understand clearly that the truth of a thought in the realm to which it belongs is no evidence for its general validity. Someone can offer me a perfectly correct proof of this or that and yet it will not hold good in a sphere to which it does not belong. Anyone, therefore, who intends to occupy himself seriously with the paths that lead to a conception of the world must recognise that the first essential is to avoid one-sidedness. That is what I specially want to bring out to-day. Now let us take a general look at some matters which will be explained in detail later on.

There are people so constituted that it is not possible for them to find the way to the Sprit, and to give them any proof of the Spirit will always be hard. They stick to something they know about, in accordance with their nature. Let us say they stick at something that makes the crudest kind of impression on them—Materialism. We need not regard as foolish the arguments they advance as a defence or proof of Materialism, for an immense amount of ingenious writing has been devoted to the subject, and it holds good in the first place for material life, for the material world and its laws.

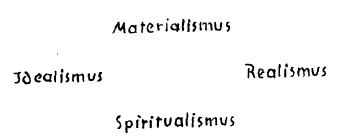

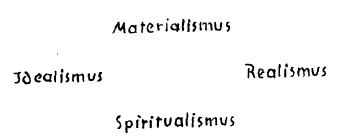

Again, there are people who, owing to a certain inwardness, are naturally predisposed to see in all that is material only the revelation of the spiritual. Naturally, they know as well as the materialists do that, externally, the material world exists; but matter, they say, is only the revelation, the manifestation, of the underlying spiritual. Such persons may take no particular interest in the material world and its laws. As all their ideas of the spiritual come to them through their own inner activity, they may go through the world with the consciousness that the true, the lofty, in which one ought to interest oneself—all genuine reality—is found only in the Spirit; that matter is only illusion, only external phantasmagoria. This would be an extreme standpoint, but it can occur, and can lead to a complete denial of material life. We should have to say of such persons that they certainly do recognize what is most real, the Spirit, but they are one-sided; they deny the significance of the material world and its laws. Much acute thinking can be enlisted in support of the conception of the universe held by these persons. Let us call their conception of the universe: Spiritism. Can we say that the Spiritists are right? As regards the Spirit, their contentions could bring to light some exceptionally correct ideas, but concerning matter and its laws they might reveal very little of any significance. Can one say the Materialists are correct in what they maintain? Yes, concerning matter and its laws they may be able to discover some exceptionally useful and valuable facts; but in speaking of the Spirit they may utter nothing but foolishness. Hence we must say that both parties are correct in their respective spheres.

There can also be persons who say: “Yes, but as to whether in truth the world contains only matter, or only spirit, I have no special knowledge; the powers of human cognition cannot cope with that. One thing is clear—there is a world spread out around us. Whether it is based upon what chemists and physicists, if they are materialists, call atoms, I know not. But I recognize the external world; that is something I see and can think about. I have no particular reason for supposing that it is or is not spiritual at root. I restrict myself to what I see around me.” From the explanations already given we can call such Realists, and their concept of the universe: Realism. Just as one can enlist endless ingenuity on behalf of Materialism or of Spiritism, and just as one can be clever about Spiritism and yet say the most foolish things on material matters, and vice versa, so one can advance the most ingenious reasons for Realism, which differs from both Spiritism and Materialism in the way I have just described.

Again, there may be other persons who speak as follows. Around us are matter and the world of material phenomena. But this world of material phenomena is in itself devoid of meaning. It has no real meaning unless there is within it a progressive tendency; unless from this external world something can emerge towards which the human soul can direct itself, independently of the world. According to this outlook, there must be a realm of ideas and ideals within the world-process. Such people are not Realists, although they pay external life its due; their view is that life has meaning only if ideas work through it and give it purpose. It was under the influence of such a mood as this that Fichte once said: Our world is the sensualised material of our duty.2“Unsere Welt ist das versinnlichte Material unserer Pflicht.” The rendering given is that of Professor Robert Adamson, in the series of Blackwood's Philosophical Classics for English readers. Alternative words for versinnlichte might be “sense-perceptible” or “tangible”. The quotation is from Fichte's work, Über den Grund unseres Glaubens an eine göttliche Weltregierung (1798). The adherents of such a world-outlook as this, which takes everything as a vehicle for the ideas that permeate the world-process, may be called Idealists and their outlook: Idealism. Beautiful and grand and glorious things have been brought forward on behalf of this Idealism. And in this realm that I have just described—where the point is to show that the world would be purposeless and meaningless if ideas were only human inventions and were not rooted in the world-process—in this realm Idealism is fully justified. But by means of it one cannot, for example, explain external reality. Hence one can distinguish this Idealism from other world-outlooks:

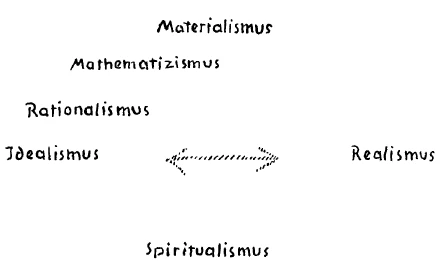

We now have side by side four justifiable world-outlooks, each with significance for its particular domain. Between Materialism and Idealism there is a certain transition. The crudest kind of materialism—one can observe it specially well in our day, although it is already on the wane—will consist in this, that people carry to an extreme the saying of Kant—Kant did not do this himself!—that in the individual sciences there is only so much real science as there is mathematics. This means that from being a materialist one can become a ready-reckoner of the universe, taking nothing as valid except a world composed of material atoms. They collide and gyrate, and then one calculates how they inter-gyrate. By this means one obtains very fine results, which show that this way of looking at things is fully justified. Thus you can get the vibration-rates for blue, red, etc.; you take the whole world as a kind of mechanical apparatus, and can reckon it up accurately. But one can become rather confused in this field. One can say to oneself: “Yes, but however complicated the machine may be, one can never get out of it anything like the perception of blue, red, etc. Thus if the brain is only a complicated machine, it can never give rise to what we know as soul-experiences.” But then one can say, as du Bois-Reymond once said: If we want to explain the world in strictly mathematical terms, we shall not be able to explain the simplest perception, but if we go outside a mathematical explanation, we shall be unscientific. The most uncompromising materialist would say, “No, I do not even calculate, for that would presuppose a superstition—it would imply that I assume that things are ordered by measure and number.” And anyone who raises himself above this crude materialism will become a mathematical thinker, and will recognize as valid only whatever can be treated mathematically. From this results a conception of the universe that really admits nothing beyond mathematical formulae. This may be called Mathematism.

Someone, however, might think this over, and after becoming a Mathematist he might say to himself: “It cannot be a superstition that the colour blue has so and so many vibrations. The world is ordered mathematically. If mathematical ideas are found to be real in the world, why should not other ideas have equal reality?” Such a person accepts this—that ideas are active in the world. But he grants validity only to those ideas that he discovers outside himself—not to any ideas that he might grasp from his inner self by some sort of intuition or inspiration, but only to those he reads from external things that are real to the senses. Such a person becomes a Rationalist, and his outlook on the world is that of Rationalism. If, in addition to the ideas that are found in this way, someone grants validity also to those gained from the moral and the intellectual realms, then he is already an Idealist. Thus a path leads from crude Materialism, by way of Mathematism and Rationalism, to Idealism.

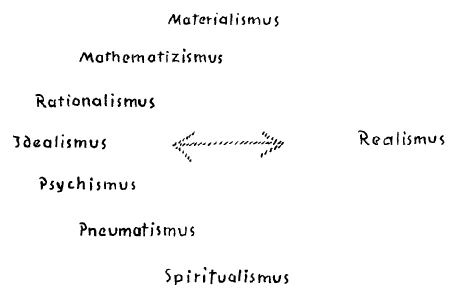

But now Idealism can be enhanced. In our age there are some men who are trying to do this. They find ideas at work in the world, and this implies that there must also be in the world some sort of beings in whom the ideas can live. Ideas cannot live just as they are in any external object, nor can they hang as it were in the air. In the nineteenth century the belief existed that ideas rule history. But this was a confusion, for ideas as such have no power to work. Hence one cannot speak of ideas in history. Anyone who understands that ideas, if they are there are all, are bound up with some being capable of having ideas, will no longer be a mere Idealist; he will move on to the supposition that ideas are connected with beings. He becomes a Psychist and his world-outlook is that Psychism. The Psychist, who in his turn can uphold his outlook with an immense amount of ingenuity, reaches it only through a kind of one-sidedness, of which he can eventually become aware.

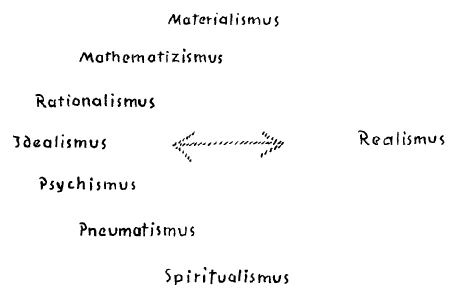

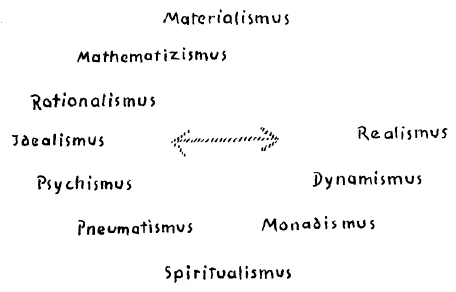

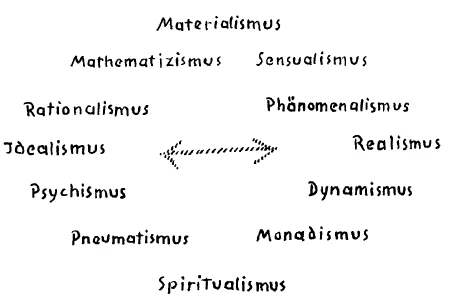

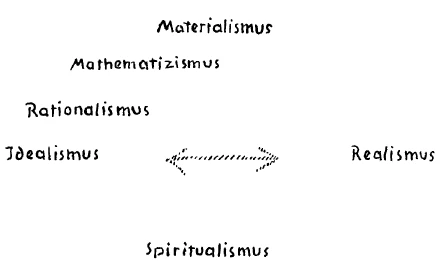

Here I must add that there are adherents of all the world-outlooks above the horizontal stroke; for the most part they are stubborn folk who, owing to some fundamental element in themselves, take this or that world-outlook and abide by it, going no further. All the beliefs listed below the line have adherents who are more easily accessible to the knowledge that individual world-outlooks each have one special standpoint only, and they more easily reach the point where they pass from one world-outlook to another.

When someone is a Psychist, and able as a thinking person to contemplate the world clearly, then he comes to the point of saying to himself that he must presuppose something actively psychic in the outside world. But directly he not only thinks, but feels sympathy for what is active and willing in man, then he says to himself: “It is not enough that there are beings who have ideas; these beings must also be active, they must be able also to do things.” But this is inconceivable unless these beings are individual beings. That is, a person of this type rises from accepting the ensoulment of the world to accepting the Spirit or the Spirits of the world. He is not yet clear whether he should accept one or a number of Spirits, but he advances from Psychism to Pneumatism to a doctrine of the Spirit.

If he has become in truth a Pneumatist, then he may well grasp what I have said in this lecture about number—that with regard to figures it is somewhat doubtful to speak of a “unity”. Then he comes to the point of saying to himself: It must therefore be a confusion to talk of one undivided Spirit, of one undivided Pneuma. And he gradually becomes able to form for himself an idea of the Spirits of the different Hierarchies. Then he becomes in the true sense a Spiritist, so that on this side there is a direct transition from Pneumatism to Spiritism.

These world-outlooks are all justified in their own field. For there are fields where Psychism acts illuminatingly, and others where Pneumatism does the same. Certainly, anyone who wishes to deliberate about an explanation of the universe as thoroughly as we have tried to do must come to Spiritism, to the acceptance of the Spirits of the Hierarchies. For to stop short at Pneumatism would in this case mean the following. If we are Spiritists, then it may happen that people will say to us: “Why so many spirits? Why bring numbers into it? Let there be One Undivided Spirit!” Anyone who goes more deeply into the matter knows that this objection is like saying: “You tell me there are two hundred midges over there. I don't see two hundred; I see only a single swarm.” Exactly so would an adherent of Pneumatism stand with regard to a Spiritist. The Spiritist sees the universe filled with the Spirits of the Hierarchies; the Pneumatist sees only the one “swarm”—only the Universal Spirit. But that comes from an inexact view.

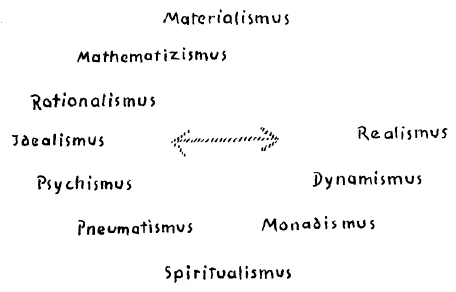

Now there is still another possibility: someone may not take the path we have tried to follow to the activities of the spiritual Hierarchies, but may still come to an acceptance of certain spiritual beings. The celebrated German philosopher, Leibnitz, was a man of this kind. Leibnitz had got beyond the prejudice that anything merely material can exist in the world. He found the actual, he sought the actual. (I have treated this more precisely in my book, Riddles of Philosophy.) His view was that a being—as, for example, the human soul—can build up existence in itself. But he formed no further ideas on the subject. He only said to himself that there is such a being that can build up existence in itself, and force concepts outwards from within itself. For Leibnitz, this being is a “Monad”. And he said to himself: “There must be many Monads, and Monads of the most varied capabilities. If I had here a bell, there would be many monads in it—as in a swarm of midges—but they would be monads that had never come even so far as to have sleep-consciousness, monads that are almost unconscious, but which nevertheless develop the dimmest of concepts within themselves. There are monads that dream; there are monads that develop waking ideas within themselves; in short, there are monads of the most varied grades.”

A person with this outlook does not come so far as to picture to himself the individual spiritual beings in concrete terms, as the Spiritist does, but he reflects in the world upon the spiritual element in the world, allowing it to remain indefinite. He calls it “Monad”—that is, he conceives of it only as though one were to say: “Yes, there is spirit in the world and there are spirits, but I describe them only by saying, ‘They are entities having varying powers of perception.’ I pick out from them an abstract characteristic. So I form for myself this one-sided world-outlook, on behalf of which as much as can be said has been said by the highly intelligent Leibnitz. In this way I develop Monadism.” Monadism is an abstract Spiritism.

But there can be persons who do not rise to the level of the Monads; they cannot concede that existence is made up of beings with the most varied conceptual powers, but at the same time they are not content to allow reality only to external phenomena; they hold that “forces” are dominant everywhere. If, for example, a stone falls to the ground, they say, “That is gravitation!” When a magnet attracts bits of iron, they say: “That is magnetic force!” They are not content with saying simply, “There is the magnet,” but they say, “The magnet presupposes that supersensibly, invisibly, a magnetic force is present, extending in all directions.” A world-outlook of this kind—which looks everywhere for forces behind phenomena—can be called Dynamism.

Then one may say: “No, to believe in ‘forces’ is superstition”—an example of this is Fritz Mauthner's Critique of Language, where you find a detailed argument to this effect. It amounts to taking your stand on the reality of the things around us. Thus by the path of Spiritism we come through Monadism and Dynamism to Realism again.

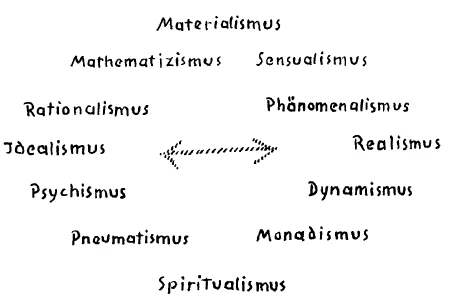

But now one can do something else still. One can say: “Certainly I believe in the world that is spread out around me, but I do not maintain any right to claim that this world is the real one. I can say of it only that it ‘appears’ to me. I have no right to say more about it.” There you have again a difference. One can say of the world that is spread out around us. “This is the real world,” but one can also say, “I am clear that there is a world which appears to me; I cannot speak of anything more. I am not saying that this world of colours and sounds, which arises only because certain processes in my eyes present themselves to me as colours, while processes in my ears present themselves to me as sounds—I am not saying that this world is the true world. It is a world of phenomena.” This is the outlook called Phenomenalism.

We can go further, and can say: “The world of phenomena we certainly have around us, but all that we believe we have in these phenomena is what we have ourselves added to them, what we have thought into them. Our own sense-impressions are all we can rightly accept. Anyone who says this—mark it well!—is not an adherent of Phenomenalism. He peels off from the phenomena everything which he thinks comes only from the understanding and the reason, and he allows validity only to sense-impressions, regarding them as some kind of message from reality.” This outlook may be called Sensationalism.

A critic of this outlook can then say: “You may reflect as much as you like on what the senses tell us and bring forward ever so ingenious reasons for your view—and ingenious reasons can be given—I take my stand on the point that nothing real exists except that which manifests itself through sense-impressions; this I accept as something material.”

This is rather like an atomist saying: “I hold that only atoms exist, and that however small they are, they have the attributes which we recognize in the physical world”—anyone who says this is a materialist. Thus, by another path, we arrive back at Materialism.

All these conceptions of the world that I have described and written down for you really exist, and they can be maintained. And it is possible to bring forward the most ingenious reasons for each of them; it is possible to adopt any one of them and with ingenious reasons to refute the others. In between these conceptions of the world one can think out yet others, but they differ only in degree from the leading types I have described, and can be traced back to them. If one wishes to learn about the web and woof of the world, then one must know that the way to it is through these twelve points of entry. There is not merely one conception of the world that can be defended, or justified, but there are twelve. And one must admit that just as many good reasons can be adduced for each and all of them as for any particular one. The world cannot be rightly considered from the one-sided standpoint of one single conception, one single mode of thought; the world discloses itself only to someone who knows that one must look at it from all sides. Just as the sun—if we go by the Copernican conception of the universe—passes through the signs of the Zodiac in order to illuminate the earth from twelve different points, so we must not adopt one standpoint, the standpoint of Idealism, or Sensationalism, or Phenomenalism, or any other conception of the world with a name of this kind; we must be in a position to go all round the world and accustom ourselves to the twelve different standpoints from which it can be contemplated. In terms of thought, all twelve standpoints are fully justifiable. For a thinker who can penetrate into the nature of thought, there is not one single conception of the world, but twelve that can be equally justified—so far justified as to permit of equally good reasons being thought out for each of them. There are twelve such justified conceptions of the world.

Tomorrow we will start from the points of view we have gained in this way, so that from the consideration of man in terms of thought we may rise to a consideration of the cosmic.

Zweiter Vortrag

Im Grunde genommen macht die Beschäftigung mit der Geisteswissenschaft ein nebenhergehendes, fortwährendes praktisches Leben in den geistigen Verrichtungen notwendig. Es ist eigentlich unmöglich, über die mancherlei Dinge, die gestern besprochen worden sind, zur völligen Klarheit zu kommen, wenn man nicht versucht, durch eine Art lebendigen Erfassens der Verrichtungen des geistigen Lebens, namentlich des denkerischen Lebens auch, mit den Dingen zurechtzukommen. Denn warum ist es im Geistesleben so, daß zum Beispiel Unklarheit herrscht über die Beziehungen der allgemeinen Begriffe, des Dreiecks im allgemeinen, zu den besonderen Vorstellungen der einzelnen Dreiecke bei Leuten, die sich gerade berufsmäßig denkerisch mit den Dingen beschäftigen? Woher kommen denn solche ganze Jahrhunderte beschäftigenden Dinge, wie das gestern angeführte Beispiel mit den hundert möglichen und den hundert wirklichen kantischen Talern? Woher kommt es denn, daß man die einfachsten Überlegungen nicht anstellt, die notwendig wären, um einzusehen, daß es so etwas wie eine pragmatische Geschichtsschreibung, wonach immer das Folgende aus dem Vorhergehenden sich herleitet, nicht geben kann? Woher kommt es, daß eine solche Überlegung nicht angestellt wird, die einen stutzig machen würde in bezug auf das, was in den weitesten Kreisen als eine eben unmögliche Art der Auffassung menschlicher Geschichte sich verbreitet hat? Woher kommen alle diese Dinge?

Sie kommen davon her, daß man sich wirklich auch dort, wo es sein sollte, viel zuwenig Mühe gibt, in einer präzisen Art die Verrichtungen des geistigen Lebens handhaben zu lernen. In unserer Zeit will ja jeder wenigstens das Folgende berechtigterweise beanspruchen können, er will sagen können: Denken, nun selbstverständlich, das kann man doch. Also fängt man an zu denken. Da gibt es Weltanschauungen in der Welt. Viele, viele Philosophen haben existiert. Man merkt, der eine hat dies, der andere jenes gesagt. Nun, daß das auch so halbwegs gescheite Leute waren, die auf vieles hätten aufmerksam werden können, was man selber als Widerspruch bei ihnen findet, darüber reflektiert man nicht, darüber denkt man nicht weiter nach. Aber man tut sich um so mehr darauf zugute, daß man doch «denken» kann. Also man kann nachdenken, was die Leute da gedacht haben, und ist überzeugt davon, daß man schon selber das Rechte finden werde. Denn man darf heute nicht auf Autorität etwas geben! Das widerspricht der Würde der Menschennatur. Man muß selber denken. Auf dem Gebiete des Denkens hält man das durchaus so.

Ich weiß nicht, ob die Leute sich überlegt haben, daß sie es auf allen anderen Gebieten des Lebens nicht so halten. So fühlt sich zum Beispiel keiner dem Autoritätsglauben oder der Autoritätssucht hingegeben, wenn er sich seinen Rock beim Schneider oder seine Schuhe beim Schuhmacher machen läßt. Er sagt nicht: Das ist unter der Würde des Menschen, daß man sich die Dinge von Menschen machen läßt, von denen man wissen kann, daß sie die entsprechenden Dinge handhaben können. Ja, man gibt vielleicht sogar zu, daß man diese Dinge lernen müsse. Bezüglich des Denkens gibt man das im praktischen Leben nicht zu, daß man Weltanschauungen auch haben müsse von dorther, wo man Denken und noch manches andere gelernt hat. Das wird man heute wirklich nur in den wenigsten Fällen zugeben.

Das ist eines, was unser Leben in den weitesten Kreisen beherrscht, was geradezu dazu beiträgt, daß der menschliche Gedanke in unserer Zeit kein sehr verbreitetes Produkt ist. Ich denke, man könnte das ja auch begreiflich finden. Denn nehmen wir an, es würden einmal alle Menschen sagen: Stiefel machen lernen, das ist eine längst nicht mehr menschenwürdige Sache; wir machen einmal alle Stiefel - so weiß ich nicht, ob dabei lauter gute Stiefel herauskommen würden. Aber jedenfalls gehen in bezug auf das Prägen richtiger Gedanken in der Weltanschauung die Menschen in der Gegenwart meistens von dieser Ansicht aus. Das ist das eine, was dazu beiträgt, daß der Satz, den ich gestern gesprochen habe, schon seine tiefere Bedeutung hat: daß der Gedanke zwar dasjenige ist, in dem der Mensch sozusagen völlig drinnen ist und den er daher in seinem Innensein überschauen kann, daß aber der Gedanke nicht so verbreitet ist, als man denken möchte. Dazu kommt allerdings in unserer Zeit noch eine ganz besondere Prätention, die allmählich darauf hinauslaufen könnte, jede Klarheit über den Gedanken überhaupt zu trüben. Auch damit muß man sich beschäftigen. Man muß wenigstens einmal den Blick darauf wenden.

Nehmen wir einmal folgendes an: Es hätte in Görlitz einen Schuhmacher namens Jakob Böhme gegeben. Und jener Schuhmacher namens Jakob Böhme hätte das Schuhmacherhandwerk gelernt, hätte gut gelernt, wie man Sohlen zuschneidet, wie man den Schuh über den Leisten formt, wie man Nägel in Sohlen und Leder hineintreibt und so weiter. Das hätte er alles aus dem Fundament heraus klar gewußt und gekonnt. Nun wäre dieser Schuhmacher namens Jakob Böhme hergegangen und hätte gesagt: Jetzt will ich einmal sehen, wie die Welt konstruiert ist. Nun, ich nehme einmal an, der Welt liegt zugrunde ein großer Leisten. Über diesen Leisten sei einmal das Weltenleder darübergezogen worden. Dann wären die Weltennägel genommen worden, und man hätte die Weltensohle durch Weltennägel in Verbindung gebracht mit dem Weltenlederüberzug. Dann hätte man die Weltenschuhwichse genommen und den ganzen Weltenschuh gewichst. So kann ich mir erklären, daß es am Morgen hell wird. Da glänzt eben die Schuhwichse der Welt. Und wenn diese Schuhwichse der Welt am Abend übertüncht ist von allem möglichen, so glänzt sie dann nicht mehr. Daher stelle ich mir vor, daß irgend jemand in der Nacht zu tun hat, um den Weltenstiefel neu zu wichsen. Und so entsteht der Unterschied zwischen Tag und Nacht. :

Nehmen wir an, Jakob Böhme hätte dies gesagt. Ja, sie lachen, weil Jakob Böhme dies allerdings nicht gesagt hat, sondern er hat für die Görlitzer Bürgerschaft anständige Schuhe gemacht, hat dazu seine Schuhmacherkunst benutzt. Er hat aber auch seine grandiosen Gedanken entfaltet, durch die er eine Weltanschauung aufbauen wollte. Da hat er zu anderem gegriffen. Er hat sich gesagt: Da würden meine Gedanken des Schuhmachens nicht ausreichen; denn will ich Weltgedanken haben, so darf ich nicht Gedanken, durch die ich Schuhe mache für die Leute, auf das Weltgebäude anwenden. Und er ist zu seinen erhabenen Gedanken über die Welt gekommen. Also jenen Jakob Böhme, den ich zuerst in der Hypothese konstruiert habe, hat es in Görlitz nicht gegeben, sondern jenen anderen, der gewußt hat, wie man es macht.

Aber jene hypothetischen Jakob Böhmes, die so sind wie jener, über den Sie gelacht haben, die existieren heute überall. Da finden wir zum Beispiel Physiker, Chemiker. Sie haben die Gesetze gelernt, nach denen man Stoffe in der Welt verbindet und trennt. Da gibt es Zoologen, die haben gelernt, wie man Tiere untersucht und beschreibt. Da gibt es Mediziner, die haben gelernt, wie man den physischen Menschenleib und das, was sie die Seele nennen, zu behandeln hat. Was tun diese? Sie sagen: Wenn man eine Weltanschauung sich suchen will, so nimmt man die Gesetze, die man in der Chemie, in der Physik oder in der Physiologie gelernt hat - andere daß es nicht geben -, und daraus konstruiert man sich eine Weltanschauung. Genauso machen es diese Menschen, wie es der eben hypothetisch konstruierte Schuhmacher gemacht hätte, wenn er den Weltenstiefel konstruiert hätte. Nur merkt man heute nicht, daß methodisch die Weltanschauungen genau ebenso zustande kommen wie jener hypothetische Weltenstiefel. Es sieht allerdings etwas grotesk aus, wenn man sich den Unterschied von Tag und Nacht durch Abnutzen des Schuhleders und durch Wichsen in der Nacht vorstellt. Aber vor einer wahren Logik ist es im Prinzip genau dasselbe, als wenn man mit den Gesetzen der Chemie, der Physik, der Biologie und Physiologie ein Weltgebäude zustande bringen will. Ganz genau dasselbe Prinzip! Es ist die ungeheure Überhebung des Physikers, des Chemikers, des Physiologen, ‚des Biologen, die nichts anderes sein wollen als Physiker, Chemiker, Physiologen, Biologen und dennoch über die ganze Welt ein Urteil haben wollen.

Es handelt sich eben überall darum, daß man den Dingen auf den Grund geht und daß man es auch nicht vermeidet, durch Zurückführung desjenigen, was nicht so durchsichtig ist, auf seine wahre Formel, ein wenig hineinzuleuchten in die Dinge. Wenn man also methodisch-logisch das alles ins Auge faßt, dann braucht man sich nicht zu verwundern, daß bei so vielen Weltanschauungsversuchen der Gegenwart eben nichts anderes herauskommt als der «Weltenstiefel». Und das ist so etwas, was hinweisen kann auf die Beschäftigung mit der Geisteswissenschaft und auf die Beschäftigung mit praktischen Denkverrichtungen, was einen geneigt machen kann, sich damit zu beschäftigen, wie man denken muß, damit man durchschauen kann, wo Unzulänglichkeiten in der Welt vorhanden sind.

Ein anderes möchte ich anführen, um zu zeigen, wo die Wurzel unzähliger Mißverständnisse gegenüber den Weltauffassungen liegt. Macht man denn nicht, wenn man sich mit Weltanschauungen beschäftigt, immer wieder und wieder die Erfahrung: da glaubt der eine dieses, der andere jenes; der eine verteidigt mit manchmal guten Gründen - denn gute Gründe kann man für alles finden - das eine, der andere mit ebenso guten Gründen das andere; und der eine widerlegt das eine ebenso gut, wie der andere mit guten Gründen widerlegt? Anhängerschaften entstehen ja in der Welt zunächst nicht dadurch, daß der eine oder der andere auf gerechtem Wege überzeugt wird von dem, was da oder dort gelehrt wird. Nehmen Sie nur einmal die Wege, die die Schüler großer Männer wandeln müssen, um zu dem oder jenem großen Manne hinzukommen, dann werden Sie sehen, daß darin für uns zwar etwas Gewichtiges in bezug auf das Karma liegt, aber hinsichtlich der Anschauungen, die heute in der äußeren Welt existieren, muß man sagen: Ob der eine nun ein Bergsonianer oder ein Haeckelianer oder dies oder jenes wird, das ist — wie gesagt, Karma erkennt ja die heutige äußere Weltanschauung nicht an -, das ist schließlich wirklich von anderen Dingen abhängig als davon, daß man durchaus nur auf dem Wege der tiefsten Überzeugung dem anhängt, zu dem man gerade geführt worden ist. Gekämpft wird hinüber und herüber. Und ich habe gestern gesagt: Es gab einmal Nominalisten, solche Menschen, welche behaupteten, die allgemeinen Begriffe hätten überhaupt keine Realität, wären bloße Namen. Sie haben Gegner gehabt, diese Nominalisten. Man nannte in der damaligen Zeit - das Wort hatte damals eine andere Bedeutung als heute — die Gegner der Nominalisten Realisten. Diese behaupteten: Die allgemeinen Begriffe sind nicht bloß Worte, sondern sie beziehen sich auf eine ganz bestimmte Realität.

Im Mittelalter wurde ja die Frage «Realismus oder Nominalismus» ganz besonders für die Theologie eine brennende auf einem Gebiete, das heute die Denker nur noch wenig beschäftigt. Denn in der Zeit, als die Frage «Nominalismus oder Realismus» auftauchte, im 11. bis 13. Jahrhundert, da war etwas, was zu dem wichtigsten menschlichen Bekenntnisse gehörte, die Frage nach den drei «göttlichen Personen», Vater, Sohn und Heiliger Geist, die ein göttliches Wesen bilden, die aber doch drei wahre Personen sein sollten. Und die Nominalisten behaupteten: Diese drei göttlichen Personen existieren nur im einzelnen, «Vater» für sich, «Sohn» für sich, «Geist» für sich; und wenn man von einem gemeinsamen Gotte spricht, der diese drei umfaßt, so ist das nur ein Name für die drei. - So schaffte der Nominalismus die Einheit in der Trinität hinweg, und die Nominalisten erklärten gegenüber den Realisten die Einheit nicht nur für logisch absurd, sondern sie hielten sogar für ketzerisch, was die Realisten behaupteten, daß die drei Personen nicht bloß eine gedachte, sondern eine reale Einheit bilden sollten.

Nominalismus und Realismus waren also Gegensätze. Und wahrhaftig, wer sich in die Literatur vertieft, die aus dem Nominalismus und Realismus hervorgegangen ist in den gekennzeichneten Jahrhunderten, der bekommt einen tiefen Einblick in das, was menschlicher Scharfsinn aufbringen kann, denn sowohl für den Nominalismus wie für den Realismus sind die scharfsinnigsten Gründe aufgebracht worden. Es war ja damals schwieriger, ein solches Denken sich anzueignen, weil es damals noch keine Buchdruckerkunst gab und man durchaus nicht so leicht dazu kam, sich an solchen Streitigkeiten zu beteiligen, wie es zum Beispiel die zwischen Nominalisten und Realisten waren; so daß der, welcher sich an solchen Streiten beteiligte, im Sinne der damaligen Zeit viel besser vorbereitet sein mußte, als heute Menschen vorbereitet sind, die sich an den Streiten beteiligen. Eine Unsumme von Scharfsinn ist aufgeboten worden, um den Realismus zu verteidigen, eine andere Unsumme von Scharfsinn ist aufgeboten worden, um den Nominalismus zu verteidigen. Woher kommt so etwas? Es ist doch betrüblich, daß es so etwas gibt. Wenn man tiefer nachdenkt, muß man sagen, daß es betrüblich ist, daß es so etwas gibt. Denn man kann sich, wenn man tiefer nachdenkt, doch sagen: Was nützt es dir denn, daß du gescheit bist? Du kannst gescheit sein und den Nominalismus verteidigen, und du kannst ebenso gescheit sein und den Nominalismus widerlegen. Man kann irre werden an der ganzen menschlichen Gescheitheit! Es ist betrüblich, auch nur einmal hinzuhotchen auf das, was mit solchen Charakteristiken gemeint ist.

Nun wollen wir einmal dem eben Gesagten etwas gegenüberstellen, was vielleicht gar nicht einmal so scharfsinnig ist wie vieles, was für den Nominalismus oder für den Realismus aufgebracht worden ist, was aber vielleicht gegenüber dem vielen einen Vorzug hat: daß es geradenwegs auf das Ziel losgeht, das heißt, daß es die Richtung findet, in der man zu denken hart.

Nehmen Sie einmal an, Sie versetzten sich in die Art, wie man allgemeine Begriffe bildet, wie man also eine Menge von Einzelheiten zusammenfaßt. Auf zweifache Weise kann man - zunächst an einem Beispiele - Einzelheiten zusammenfassen. Man kann da so, wie das der Mensch in seinem Leben tut, durch die Welt schlendern und eine Reihe gewisser Tiere sehen, welche seidig oder wollig, verschieden gefärbt sind, Schnauzhaare haben und die zu gewissen Zeiten eine eigentümliche, an das menschliche Waschen erinnernde Tätigkeit verrichten, die Mäuse fressen und so weiter. Man kann solche Wesen, die man so beobachtet hat, Katzen nennen. Dann hat man einen allgemeinen Begriff, Katze, gebildet. Alle diese Wesen, die man so gesehen hat, haben etwas zu tun mit dem, was man die Katzen nennt.

Aber nehmen wir an, man machte das Folgende. Man habe ein reiches Leben durchgemacht, und zwar ein solches Leben, das einen zusammengebracht hat mit recht vielen Katzenbesitzern oder -besitzerinnen, und dabei habe man gefunden, daß eine große Anzahl von Katzenbesitzern ihre Katze «Mufti» genannt haben. Da man das in sehr vielen Fällen gefunden hat, so faßt man alle die Wesen, die man mit dem Namen Mufti belegt gefunden hat, zusammen unter dem Namen «die Mufti». Äußerlich angesehen, haben wir den allgemeinen Begriff Katze und den allgemeinen Begriff Mufti. Dasselbe Faktum liegt vor, der allgemeine Begriff; und zahlreiche Einzelwesen gehöten beide Male unter den allgemeinen Begriff. Dennoch wird niemand behaupten, daß der allgemeine Begriff Mufti eine gleiche Bedeutung habe mit dem allgemeinen Begriffe Katze. Hier haben Sie in der Realität den Unterschied wirklich gegeben. Das heißt, bei dem, was man verübt hat, indem man den allgemeinen Begriff Mufti gebildet hat, der nur eine Zusammenfassung von Namen ist, die als Eigennamen gelten müssen, dabei hat man sich nach dem Nominalismus gerichtet und mit Recht; und indem man den allgemeinen Begriff Katze gebildet hat, hat man sich nach dem Realismus gerichtet und mit Recht. Für den einen Fall ist der Nominalismus richtig, für den anderen der Realismus. Beide sind richtig. Man muß nur diese Dinge in ihren richtigen Gebieten anwenden. Und wenn die beiden richtig sind, dann ist es nicht zu verwundern, wenn man gute Gründe für das eine oder das andere aufbringen kann. Ich habe nur ein etwas groteskes Beispiel mit dem Namen Mufti gebraucht. Aber ich könnte ein viel bedeutsameres Beispiel Ihnen anführen und will dieses Beispiel gerade einmal vor Ihnen ins Auge fassen.

Es gibt ein ganzes Gebiet im Umkreis unserer äußeren Erfahrung, für welches der Nominalismus, das heißt die Vorstellung, daß das Zusammenfassende nur ein Name ist, seine volle Berechtigung hat. Es gibt «eins», es gibt «zwei», es gibt «dei», «vier», «fünf» und so weiter. Aber unmöglich kann jemand, der die Sachlage überschaut, in dem Ausdruck «Zahl» etwas finden, was wirklich eine Existenz hat. Die Zahl hat keine Existenz. «Eins», «zwei», «drei», «fünf», «sechs» und so weiter, das hat Existenz. Das aber, was ich gestern gesagt habe, daß man, um den allgemeinen Begriff zu finden, das Entsprechende in Bewegung übergehen lassen soll, kann man bei dem Begriffe Zahl nicht machen. Denn die Eins geht nie in die Zwei über; man muß immer eins dazugeben. Auch nicht im Gedanken geht die Eins in die Zwei über, die Zwei in die Drei auch nicht. Es existieren nur einzelne Zahlen, nicht die Zahl im allgemeinen. Für das, was in den Zahlen vorhanden ist, ist der Nominalismus absolut richtig; für das, was so vorhanden ist wie das einzelne Tier gegenüber seiner Gattung, ist der Realismus absolut richtig. Denn unmöglich kann ein Hirsch und wieder ein Hirsch und wieder ein Hirsch existieren, ohne daß die Gattung Hirsch existiert. «Zwei» kann für sich existieren, «eins», «sieben» und so weiter kann für sich existieren. Insofern aber das Wirkliche in der Zahl auftritt, ist das, was Zahl ist, ein Einzelnes, und der Ausdruck Zahl hat keine irgendwie geartete Existenz. Ein Unterschied ist eben zwischen den äußeren Dingen und ihrer Beziehung zu den allgemeinen Begriffen, und das eine muß im Stile des Nominalismus, das andere im Stile des Realismus behandelt werden.

Auf diese Weise kommen wir, indem wir den Gedanken einfach die richtige Richtung geben, zu etwas ganz anderem. Jetzt beginnen wir zu verstehen, warum so viele Weltanschauungsstreitigkeiten in der Welt existieren. Die Menschen sind im allgemeinen nicht geneigt, wenn sie eines begriffen haben, auch noch das andere zu begreifen. Wenn einer einmal auf einem Gebiete begriffen hat: Allgemeine Begriffe haben keine Existenz —, so verallgemeinert er das, was er erkannt hat, auf die ganze Welt und ihre Einrichtung. Dieser Satz: Allgemeine Begriffe haben keine Existenz - ist nicht falsch; denn er ist für das Gebiet, das der Betreffende angeschaut hat, richtig. Falsch ist nur die Verallgemeinerung. Es ist so wesentlich, wenn man überhaupt über das Denken sich eine Vorstellung machen will, daß man sich darüber klar wird, daß die Wahrheit eines Gedankens auf seinem Gebiete noch nichts aussagt über die allgemeine Gültigkeit eines Gedankens. Ein Gedanke kann durchaus auf seinem Gebiete richtig sein; aber nichts wird dadurch ausgemacht über die allgemeine Gültigkeit des Gedankens. Beweist man mir daher dieses oder jenes, und beweist man es mir noch so richtig, unmöglich kann es sein, dieses also Bewiesene auf ein Gebiet anzuwenden, auf das es nicht hingehört. Es ist daher notwendig, daß sich der, welcher sich ernsthaft mit den Wegen beschäftigen will, die zu einer Weltanschauung führen, vor allen Dingen damit bekannt macht, daß Einseitigkeit der größte Feind aller Weltanschauungen ist und daß es vor allen Dingen nötig ist, die Einseitigkeit zu meiden. Einseitigkeit müssen wir meiden. Das ist das, worauf ich insbesondere heute hindeuten will, wie wir nötig haben, Einseitigkeiten zu meiden.

Fassen wir zunächst heute das, was in den nächsten Vorträgen im einzelnen seine Erklärung finden soll, so ins Auge, daß wir uns zunächst einen Überblick darüber verschaffen.

Es kann Menschen geben, welche einmal so veranlagt sind, daß es ihnen unmöglich ist, den Weg zum Geiste zu finden. Es wird schwer werden, solchen Menschen das Geistige jemals zu beweisen. Sie bleiben bei dem stehen, wovon sie etwas wissen, wovon etwas zu wissen sie veranlagt sind. Sie bleiben, sagen wir, bei dem stehen, was den grobklotzigsten Eindruck auf sie macht, beim Materiellen. Ein solcher Mensch ist ein Materialist, und seine Weltanschauung ist Materialismus. Man hat nicht nötig, das, was von den Materialisten zur Verteidigung, zum Beweise des Materialismus aufgebracht worden ist, immer töricht zu finden, denn es ist ungeheuer viel Scharfsinniges auf diesem Gebiete geschrieben worden. Was geschrieben worden ist, das gilt zunächst für das materielle Gebiet des Lebens, gilt für die Welt des Materiellen und ihre Gesetze.

Andere Menschen kann es geben, die sind durch eine gewisse Innerlichkeit von vornherein dazu veranlagt, in allem Materiellen nur die Offenbarung des Geistigen zu sehen. Sie wissen natürlich so gut wie die Materialisten, daß äußerlich Materielles vorhanden ist; aber sie sagen: Das Materielle ist nur die Offenbarung, die Manifestation des zugrunde liegenden Geistigen. Solche Menschen interessieren sich vielleicht gar nicht besonders für die materielle Welt und ihre Gesetze. Sie gehen vielleicht, indem sie in sich alles bewegen, was ihnen Vorstellungen vom Geistigen geben kann, mit dem Bewußtsein durch die Welt: Das Wahre, das Hohe, das, womit man sich beschäftigen soll, was wirklich Realität hat, ist doch nur der Geist; die Materie ist doch nur Täuschung, ist nur eine äußere Phantasmagorie. Es wäre das ein extremer Standpunkt, aber es kann ihn geben, und er kann bis zu einer völligen Leugnung des materiellen Lebens führen. Wir würden von solchen Menschen sagen müssen: Sie erkennen voll an, was allerdings das Realste ist, den Geist; aber sie sind einseitig, sie leugnen die Bedeutung des Materiellen und seiner Gesetze. Viel Scharfsinn wird sich aufbringen lassen, um die Weltanschauung solcher Menschen zu vertreten. Nennen wir die Weltanschauung solcher Menschen Spiritualismus. Kann man sagen, daß die Spiritualisten recht haben? Für den Geist werden ihre Behauptungen außerordentlich Richtiges zutage fördern können, doch über das Materielle und seine Gesetze werden sie vielleicht wenig Bedeutsames zutage fördern können. Kann man sagen, daß die Materialisten mit ihren Behauptungen recht haben? Ja, über die Materie und ihre Gesetze werden sie vielleicht außerordentlich Nützliches und Wertvolles zutage fördern können; wenn sie aber über den Geist sprechen, dann werden sie vielleicht nur Torheiten herausbringen. Wir müssen also sagen: Für ihre Gebiete haben die Bekenner dieser Weltanschauungen recht.

Es kann Menschen geben, die sagen: Ja, ob es nun in der Welt der Wahrheit nur Materie oder nur Geist gibt, darüber kann ich nichts Besonderes wissen; darauf kann sich das menschliche Erkenntnisvermögen überhaupt nicht beziehen. Klar ist nur das eine, daß eine Welt um uns ist, die sich ausbreitet. Ob ihr das zugrunde liegt, was die Chemiker, die Physiker, wenn sie Materialisten werden, die Atome der Materie nennen, das weiß ich nicht. Ich erkenne aber die Welt an, die um mich herum ausgebreitet ist; die sehe ich, über die kann ich denken. Ob ihr noch ein Geist zugrunde liegt oder nicht, darüber etwas anzunehmen, habe ich keine besondere Veranlassung. Ich halte mich an das, was um mich herum ausgebreitet ist. — Solche Menschen kann man mit etwas anderer Wortbedeutung, als ich das Wort vorher brauchte, Realisten nennen und ihre Weltanschauung Realismus. Genau ebenso, wie man unendlichen Scharfsinn aufbringen kann für den Materialismus wie für den Spiritualismus und wie man daneben auch sehr Scharfsinniges über den Spiritualismus und die größten Torheiten über das Materielle sagen kann, wie man sehr scharfsinnig über die Materie und sehr töricht über das Spirituelle sprechen kann, so kann man die scharfsinnigsten Gründe für den Realismus aufbringen, der weder Spiritualismus noch Materialismus ist, sondern das, was ich eben jetzt charakterisiert habe.

Es kann aber noch andere Menschen geben, die etwa folgendes sagen. Um uns herum ist die Materie und die Welt der materiellen Erscheinungen. Aber die Welt der materiellen Erscheinungen ist eigentlich in sich sinnleer. Sie hat keinen rechten Sinn, wenn nicht in ihr jene Tendenz liegt, die sich eben bewegt nach vorwärts, wenn nicht aus dieser Welt, die da um uns herum ausgebreitet ist, das geboren werden kann, wonach die Menschenseele sich richten kann als nicht in der Welt enthalten, die um uns herum ausgebreitet ist. Es muß nach der Anschauung solcher Menschen das Ideelle und das Ideale im Weltprozesse drinnen sein. Solche Menschen geben den realen Weltprozessen ihr Recht. Sie sind nicht Realisten, trotzdem sie dem realen Leben recht geben, sondern sie sind der Anschauung, das reale Leben muß durchtränkt werden von dem Ideellen, nur dann bekommt es einen Sinn. - In einem Anfluge von solcher Stimmung hat Fichte einmal gesagt: Alle Welt, die sich um uns herum ausbreitet, ist das versinnlichte Material für die Pflichterfüllung. Die Vertreter solcher Weltanschauung, die alles nur Mittel sein läßt für Ideen, die den Weltprozeß durchdringen, kann man Idealisten nennen und ihre Weltanschauung Idealismus. Schönes und Großes und Herrliches ist für diesen Idealismus vorgebracht worden. Und auf dem Gebiete, das ich eben charakterisiert habe, wo es darauf ankommt, zu zeigen, wie die Welt zweck- und sinnlos wäre, wenn die Ideen nur menschliche Phantasiegebilde wären und nicht im Weltprozesse drinnen wirklich begründet wären, auf diesem Gebiete hat der Idealismus seine volle Bedeutung. Aber mit diesem Idealismus kann man zum Beispiel die äußere Wirklichkeit, die äußere Realität des Realisten nicht erklären. Daher hat man zu unterscheiden von den anderen eine Weltanschauung, die Idealismus genannt werden kann,

Wir haben jetzt schon vier nebeneinander berechtigte Weltanschauungen, von denen jede ihre Bedeutung hat für ihr besonderes Gebiet. Zwischen dem Materialismus und dem Idealismus ist ein gewisser Übergang. Der ganz grobe Materialismus — man kann ihn ja besonders in unserer Zeit, obwohl er heute schon im Abfluten ist, gut beobachten - wird darin bestehen, daß man bis zum Extrem ausbildet das Kantische Diktum - Kant selber hat es nicht getan! -, daß in den einzelnen Wissenschaften nur so viel wirkliche Wissenschaft ist, als darin Mathematik ist. Das heißt, man kann vom Materialisten zum Rechenknecht des Universums werden, indem man nichts anderes gelten läßt als die Welt, angefüllt mit materiellen Atomen. Sie stoßen sich, wirbeln durcheinander, und man rechnet dann aus, wie die Atome durcheinanderwirbeln. Da bekommt man sehr schöne Resultate heraus, was bezeugen mag, daß diese Weltanschauung ihre volle Berechtigung hat. So bekommt man zum Beispiel die Schwingungszahlen für Blau, für Rot und so weiter; man bekommt die ganze Welt wie eine Art von mechanischem Apparat und kann diesen fein berechnen. Man kann aber etwas irre werden an dieser Sache. Man kann sich zum Beispiel sagen: Ja, aber wenn man eine noch so komplizierte Maschine hat, so kann doch aus dieser Maschine niemals, selbst wenn sie noch so kompliziert sich bewegt, hervorgehen, wie man etwa Blau, Rot und so weiter empfindet. Wenn also das Gehirn nur eine komplizierte Maschine ist, so kann doch aus dem Gehirn nicht das hervorgehen, was man als Seelenerlebnisse hat. Aber man kann dann sagen, wie einstmals Du Bors-Reymond gesagt hat: Man wird, wenn man die Welt nur mathematisch erklären will, zwar die einfachste Empfindung nicht erklären können; will man aber bei der mathematischen Erklärung nicht stehenbleiben, so wird man unwissenschaftlich. -— Der grobe Materialist würde sagen: Nein, ich rechne auch nicht; denn das setzt schon einen Aberglauben voraus, den Aberglauben, daß ich annehme, daß die Dinge nach Maß und Zahl geordnet sind. Und wer nun über diesen groben Materialismus sich erhebt, wird ein mathematischer Kopf und läßt nur das als wirklich gelten, was eben in Rechenformeln gebracht werden kann. Das ergibt eine Weltanschauung, die eigentlich nichts gelten läßt als die mathematische Formel. Man kann sie Mathematizismus nennen.

Es kann sich aber einer nun überlegen und dann, nachdem er Mathematizist gewesen ist, sich sagen: Das kann kein Aberglaube sein, daß die blaue Farbe soundso viele Schwingungen hat. Mathematisch ist nun einmal doch die Welt angeordnet. Warum sollten, wenn mathematische Ideen in der Welt verwirklicht sind, nicht auch andere Ideen in der Welt verwirklicht sein? Ein solcher nimmt an: Es leben doch Ideen in der Welt. Aber er läßt nur diejenigen Ideen gelten, die er findet, nicht solche Ideen, die er von innen heraus etwa durch irgendeine Intuition oder Inspiration erfassen würde, sondern nur die, welche er von den äußerlich sinnlich-realen Dingen abliest. Ein solcher Mensch wird Rationalist, und seine Weltanschauung ist Rationalismus. — Läßt man zu den Ideen, die man findet, auch noch diejenigen gelten, die man aus dem Moralischen, aus dem Intellektuellen heraus gewinnt, dann ist man schon Idealist. So geht ein Weg von dem grobklotzigen Materialismus über den Mathematismus und Rationalismus zum Idealismus.

Der Idealismus kann aber nun gesteigert werden. In unserer Zeit finden sich einige Menschen, welche den Idealismus zu steigern versuchen. Sie finden ja Ideen in der Welt. Wenn man Ideen findet, dann muß auch solche Wesensart in der Welt vorhanden sein, in der Ideen leben könnten. In irgendeinem äußeren Dinge könnten doch nicht so ohne weiteres Ideen leben. Ideen können auch nicht gleichsam in der Luft hängen. Es hat zwar im 19. Jahrhundert den Glauben gegeben, daß Ideen die Geschichte beherrschen. Es war dies aber nur eine Unklarheit; denn Ideen als solche haben keine Kraft zum Wirken. Daher kann man von Ideen in der Geschichte nicht sprechen. Wer da einsieht, daß Ideen, wenn sie überhaupt da sein sollen, an ein Wesen gebunden sind, das Ideen eben haben kann, der wird nicht mehr bloßer Idealist sein, sondern er schreitet vor zu der Annahme, daß die Ideen an Wesen gebunden sind. Er wird Psychist, und seine Weltanschauung ist Psychismus. Der Psychist, der wieder ungeheuer viel Scharfsinn für seine Weltanschauung aufbringen kann, kommt zu dieser Weltanschauung auch nur durch eine Einseitigkeit, die er eventuell bemerken kann.

Ich muß hier gleich einfügen: Für alle die Weltanschauungen, die ich über den horizontalen Strich schreiben werde, gibt es Anhänger, und diese Anhänger sind zumeist Starrköpfe, die diese oder jene Weltanschauung durch irgendwelche Grundbedingungen, die sie in sich haben, nehmen und dabei stehenbleiben. Alles, was unter diesem Strich liegt (siehe Skizze), hat Bekenner, die leichter zugänglich sind der Erkenntnis, daß die einzelnen Weltanschauungen immer nur von einem bestimmten Gesichtspunkte aus die Dinge anschen, und die daher leichter dazu kommen, von der einen in die andere Weltanschauung überzugehen.

Wenn jemand Psychist ist und geneigt, weil er Erkenntnismensch ist, die Welt kontemplativ zu betrachten, so kommt er dazu, sich zu sagen, er muß in der Welt Psychisches voraussetzen. In dem Augenblicke aber, wo er nicht nur Erkenntnismensch ist, sondern wo er in ebensolcher Weise eine Sympathie für das Aktive, für das Tätige, für das Willensartige in der Menschennatur hat, da sagt er sich: Es genügt nicht, daß Wesen da sind, die nur Ideen haben können; diese Wesen müssen auch etwas Aktives haben, müssen auch handeln können. Das ist aber nicht zu denken, ohne daß diese Wesen individuelle Wesen sind. Das heißt, ein solcher steigt auf von der Annahme der Beseeltheit der Welt zu der Annahme des Geistes oder der Geister in der Welt. Es ist sich noch nicht klar, ob er einen oder mehrere Geistwesen annehmen soll, aber er steigt auf vom Psychismus zum Pneumatismus, zur Geistlehre.

Ist einer in Wirklichkeit Pneumatist geworden, so kann es durchaus vorkommen, daß er das einsieht, was ich heute über die Zahl gesagt habe, daß es in bezug auf die Zahlen in der Tat etwas Bedenkliches hat, von einer Einheit zu sprechen. Dann kommt er dazu, sich zu sagen: Dann wird es also eine Verwortrenheit sein, von einem einheitlichen Geist, von einem einheitlichen Pneuma zu reden. Und er kommt dann allmählich dazu, von den Geistern der verschiedenen Hierarchien sich eine Vorstellung bilden zu können. Er wird dann im echten Sinne Spiritualist, so daß also auf dieser Seite ein unmittelbarer Übergang vom Pneumatismus zum Spiritualismus ist.

Alles, was ich auf die Tafel geschrieben habe, sind Weltanschauungen, die für ihre Gebiete ihre Berechtigung haben. Denn es gibt Gebiete, für die der Psychismus erklärend wirkt, es gibt Gebiete, für die der Pneumatismus erklärend wirkt. Will man allerdings so gründlich mit der Welterklärung zu Rate gehen, wie wir es versucht haben, dann muß man zum Spiritualismus kommen, zu der Annahme der Geister der Hierarchien. Dann kann man nicht beim Pneumatismus stehenbleiben; denn beim Pneumatismus stehenbleiben würde in diesem Falle das Folgende heißen. Wenn wir Spiritualisten sind, kann es uns begegnen, daß die Menschen sagen: Warum da so viele Geister? Warum da die Zahl anwenden? Es gibt einen einheitlichen Allgeist! - Wer sich tiefer auf die Sache einläßt, der weiß, daß es mit diesem Einwande ebenso ist, wie wenn jemand sagt: Da sagst du mir, dort wären zweihundert Mücken. Ich sehe aber keine zweihundert Mücken, ich sehe nur einen einzigen Mückenschwarm. — Genau so würde sich der Anhänger des Pneumatismus, des Pantheismus und so weiter gegenüber dem Spiritualisten verhalten. Der Spiritualist sieht die Welt erfüllt mit den Geistern der Hierarchien; der Pantheist sieht nur den einen Schwarm, sieht nur den einheitlichen Allgeist. Aber das beruht nur auf einer Ungenauigkeit des Anschauens. Materialismus

Nun gibt es noch eine andere Möglichkeit: die, daß jemand nicht auf den Wegen, die wir zu gehen versucht haben, zu dem Wirken geistiger Wesenheiten kommt, daß er aber doch zu der Annahme gewisser geistiger Grundwesen der Welt kommt. Ein solcher Mensch war zum Beispiel Leibniz, der berühmte deutsche Philosoph. Leibniz war hinaus über das Vorurteil, daß irgend etwas bloß materiell in der Welt existieren könne. Er fand das Reale, suchte das Reale. Das Genauere habe ich in meinem Buche «Die Rätsel der Philosophie» dargestellt. Er war der Anschauung, daß es ein Wesen gibt, das in sich die Existenz erbilden kann, wie zum Beispiel die Menschenseele. Aber er machte sich nicht weitere Begriffe darüber. Er sagte sich nur, daß es ein solches Wesen gibt, das in sich die Existenz erbilden kann, das Vorstellungen aus sich heraustreibt. Das ist für Leibniz eine Monade. Und er sagte sich: Es muß viele Monaden geben und Monaden von der verschiedensten Klarheit. Wenn ich hier eine Glocke habe, so sind dort viele Monaden drinnen - wie in einem Mückenschwarm -, aber Monaden, die nicht einmal bis zum Schlafbewußtsein kommen, Monaden, die fast unbewußt sind, die aber doch dunkelste Vorstellungen in sich entwickeln. Es gibt Monaden, die träumen, es gibt Monaden, die wache Vorstellungen in sich entwickeln, kurz, Monaden der verschiedensten Grade. — Ein solcher. Mensch kommt nicht dazu, sich das Konkrete der einzelnen geistigen Wesenheiten so vorzustellen wie der Spiritualist; aber er reflektiert in der Welt auf das Geistige, das er nur unbestimmt sein läßt. Er nennt es Monade, das heißt, er kümmert sich nur um den Vorstellungscharakter, als wenn man sagen würde: Ja, Geist, Geister sind in der Welt; aber ich beschreibe sie nur so, daß ich sage, sie sind verschiedenartig vorstellende Wesen. Eine abstrakte Eigenschaft nehme ich aus ihnen heraus. Da bilde ich mir diese einseitige Weltanschauung aus, für die vor allem so viel vorgebracht werden kann, als der geistvolle Leibniz für sie vorgebracht hat. So bilde ich den Monadismus aus. - Der Monadismus ist ein abstrakter Spiritualismus.

Es kann aber Menschen geben, die sich nicht bis zur Monade erheben, die nicht zugeben können, daß dasjenige, was existiert, Wesen sind von verschiedenem Grade des Vorstellungsvermögens, die aber auch nicht etwa damit zufrieden sind, daß sie nur zugeben, was sich in der äußeren Realität ausbreitet, sondern sie lassen das, was sich in der äußeren Realität ausbreitet, überall von Kräften beherrscht sein. Wenn zum Beispiel ein Stein zur Erde fällt, so sagen sie: Da ist die Schwerkraft. Wenn ein Magnet Eisenspäne anzieht, so sagen sie: Da ist die magnetische Kraft. Sie begnügen sich nicht bloß damit zu sagen: Da ist der Magnet - sondern sie sagen: Der Magnet setzt voraus, daß übersinnlich, unsichtbar die magnetische Kraft vorhanden ist, die sich überall ausbreitet. Man kann eine solche Weltanschauung bilden, die überall die Kräfte zu dem sucht, was in der Welt vorgeht, und kann sie Dynamismus nennen.

Dann kann man auch sagen: Nein, an Kräfte zu glauben, das ist Aberglaube! Ein Beispiel dafür, wie einer ausführlicher darstellt, wie an Kräfte zu glauben Aberglaube ist, haben Sie in Fritz Mauthners «Kritik der Sprache». In diesem Falle bleibt man bei dem stehen, was sich real um uns herum ausbreitet. Wir kommen also auf diesem Wege vom Spiritualismus über den Monadismus und Dynamismus wiederum zum Realismus.

Nun kann man aber auch noch etwas anderes machen. Man kann sagen: Gewiß, ich halte mich an die Welt, die mich ringsherum umgibt. Aber ich behaupte nicht, daß ich ein Recht habe zu sagen, diese Materialismus Welt sei die wirkliche. Ich weiß nur von ihr zu sagen, daß sie mir erscheint. Und zu mehr habe ich überhaupt nicht Recht, als zu sagen: Diese Welt erscheint mir. Ich habe kein Recht, von ihr mehr zu sagen. — Das ist also ein Unterschied. Man kann von dieser Welt, die sich um uns herum ausbreitet, sagen, sie ist die reale Welt. Aber man kann auch sagen: Von einer anderen Welt kann ich nicht reden; aber ich bin mir klar, daß es die Welt ist, die mir erscheint. Ich rede nicht davon, daß diese Welt von Farben und Tönen, die doch nur dadurch entsteht, daß sich in meinem Auge gewisse Prozesse abspielen, die sich mir als Farben zeigen, daß sich in meinem Ohr Prozesse abspielen, die sich mir als Töne zeigen und so weiter, daß diese Welt die wahre ist. Sie ist die Welt der Phänomene. - Phänomenalismus ist die Weltanschauung, um die es sich hier handeln würde.

Man kann aber weiter gehen und kann sagen: Die Welt der Phänomene haben wir zwar um uns herum. Aber alles, was wir in diesen Phänomenen zu haben glauben so, daß wir es selber hinzugegeben haben, daß wir es selber hinzugedacht haben - das haben wir eben hinzugedacht zu den Phänomenen. Berechtigt ist aber nur das, was uns die Sinne sagen. — Merken Sie wohl, ein solcher Mensch, der dieses sagt, ist nicht ein Anhänger des Phänomenalismus, sondern er schält von dem Phänomen das los, wovon er glaubt, daß es nur aus dem Verstande und aus der Vernunft kommt, und er läßt gelten, als irgendwie von der Realität angekündigt, was die Sinne als Eindrücke geben. Diese Weltanschauung kann man Sensualismus nennen.

<

Greift man dazu, zu sagen: Mögt ihr nachdenken darüber, daß das die Sinne sagen, und mögt ihr noch so scharfsinnige Gründe dafür anführen - man kann scharfsinnige Gründe dafür anführen -, ich stelle mich auf den Standpunkt, es gibt nur das, was so aussieht wie das, was die Sinne sagen; das lasse ich als Materielles gelten - wie etwa der Atomist, der da sagt: Ich nehme an, es existieren nur Atome, und wenn sie noch so klein sind, sie haben die Eigenschaften, die man in der physischen Welt kennt -, dann ist man wieder Matertalist. Wir sind also auf dem anderen Wege wieder beim Materialismus angekommen.

Was ich Ihnen hier als Weltanschauungen aufgeschrieben und charakterisiert habe, das gibt es, das kann verteidigt werden. Und es ist möglich, für jede einzelne der Weltanschauungen die scharfsinnigsten Gründe vorzubringen, es ist möglich, sich auf den Standpunkt jeder dieser Weltanschauungen zu stellen und mit scharfsinnigen Gründen die anderen Weltanschauungen zu widerlegen. Man kann zwischen diesen Weltanschauungen noch andere ausdenken; die sind aber nur gradweise von den angeführten verschieden und lassen sich auf die Haupttypen zurückführen. Will man das Gewebe der Welt kennenlernen, dann muß man wissen, daß man es durch diese zwölf Eingangstore kennenlernt. Es gibt nicht eine Weltanschauung, die sich verteidigen läßt, die berechtigt ist, sondern es gibt zwölf Weltanschauungen. Und man muß zugeben: Gerade so viele gute Gründe wie für die eine Weltanschauung, so viele gute Gründe lassen sich für jede andere der zwölf Weltanschauungen vorbringen. Die Welt läßt sich nicht von dem einseitigen Standpunkte einer Weltanschauung, eines Gedankens aus betrachten, sondern die Welt enthüllt sich nur dem, der weiß, daß man um sie herumgehen muß. Genau ebenso, wie die Sonne, auch wenn wir die kopernikanische Weltanschauung zugrunde legen, durch die Tierkreiszeichen geht, um von zwölf verschiedenen Punkten aus die Erde zu beleuchten, ebenso muß man nicht auf eine Standpunkt - auf den Standpunkt des Idealismus, des Sensualismus, des Phänomenalismus oder irgendeiner Weltanschauung, die einen solchen Namen tragen kann - sich stellen, sondern man muß in der Lage sein, um die Welt herumgehen zu können und sich einleben zu können in die zwölf verschiedenen Standpunkte, von denen aus man die Welt betrachten kann. Denkerisch sind alle zwölf verschiedenen Standpunkte voll berechtigt. Nicht eine Weltanschauung gibt es für den Denker, der in die Natur des Denkens eindringen kann, sondern zwölf gleichberechtigte, insofern gleichberechtigte, als sich gleich gute Gründe vom Denken aus für jede vorbringen lassen. Zwölf solche gleichberechtigte Weltanschauungen gibt es. Von diesem dadurch gewonnenen Gesichtspunkte aus wollen wir morgen weiter reden, damit wir uns von der denkerischen Betrachtung des Menschen zu der Betrachtung des Kosmischen hinaufschwingen.

Second Lecture

Fundamentally, engaging in spiritual science requires a parallel, ongoing practical life in spiritual activities. It is actually impossible to gain complete clarity about the various things that were discussed yesterday unless one tries to come to terms with them through a kind of living grasp of the activities of spiritual life, especially of the life of thought. For why is it that in intellectual life, for example, there is confusion about the relationship between general concepts, such as the triangle in general, and the particular ideas of individual triangles among people who are professionally engaged in thinking about such things? Where do things that have occupied people for centuries come from, such as yesterday's example of the hundred possible and the hundred real Kantian thalers? Why is it that people do not make the simplest considerations that would be necessary to see that there can be no such thing as pragmatic historiography, according to which what follows always derives from what precedes? Why is it that no one makes the kind of considerations that would make us pause and question what has become widespread in the broadest circles as an impossible way of understanding human history? Where do all these things come from?