Wonders of the World, Ordeals of the Soul, Revelations of the Spirit

GA 129

20 August 1911, Munich

3. Nature and Spirit. Zeus, Poseidon and Pluto as macrocosmic counterparts of the human bodily sheaths. An occult sign.

In this course of lectures I hope to be able to give you a survey of some important truths of Spiritual Science from one particular aspect. It is perhaps only towards the end of the course that you will be able to see how the threads all hang together. In the two lectures just given I dwelt a good deal upon the Mystery of Eleusis and upon Greek mythology, and I shall still often have occasion to refer to the performances we have seen. But I also have another purpose, which you will recognise at the end of the course. I want this evening to bring home to you from another direction how Spiritual Science in our day is aspiring towards that mighty archetypal wisdom of which we have caught a glimpse, how it throws light upon those great figures and images and upon the tidings of the Mysteries which have come down to us from ancient Greece. If we are to grasp the whole mission of Spiritual Science today we shall have to recognise that many concepts and ideas which obtain today have to be changed. Contemporary humanity is often very short-sighted, it scarcely gives a thought to anything beyond the immediate future. To evoke a feeling that we must change our very manner of thinking if we are to enter deeply into the mission of Spiritual Science—that is why I draw attention to the completely different view of the world and of life, and of the relation of man to the spiritual world, held by the Greeks. For in all this the Greek attitude of heart and soul was very different from that of modern man.

Let me begin today by mentioning just one thing. There is a concept, an idea, very familiar to you all, an idea which not only finds common expression in the vocabulary of all languages, but which has also tended to take on a certain scientific connotation. It is the word NATURE. When the word ‘nature’ is used in any context it at once arouses in modern man a whole number of ideas. We think of nature as the opposite of soul or spirit. Now what the man of today means by ‘nature’ simply did not exist for Greek thought. You have to eliminate altogether what you mean today by the term ‘nature’ if you wish to enter into the thought of ancient Greece. The contrast between nature and spirit which we today experience was unknown to the Greeks. When the Greek directed his eye to the processes which took place in wood and meadow, in sun and moon, in the world of the stars, he did not yet experience a natural existence devoid of spirit, but everything which happened in the world was as much the deed of spiritual Beings as for us a movement of our hand is an expression of our own soul-activity. When we move our hand from left to right, we know that a mental activity lies behind this movement, and we do not talk of an opposition between the mere movement of the hand and our will, but we know that the movement of the hand and our will, as an impulse of movement, constitute a unity. We still feel the unity when we make a gesture which our mind directs. But when we direct our gaze upon the course of sun and moon, when we become aware of the currents of air in the wind, then we no longer see in these things, as the Greeks did, the outer gestures, the moving hand so to say, of divine-spiritual Beings, but we see something outside us which we study according to abstract laws, mathematical-mechanical laws. Such a nature—a nature which is calculated according to purely external mathematical-mechanical laws, a nature which is not simply the physiognomy of divine-spiritual activity—was unknown to the Greeks. We shall hear how the concept ‘nature’ as understood by modern man gradually came to birth.

Thus in those ancient times Spirit and Nature were in full harmony with one another. Consequently what we today call a wonder, a miracle, did not bear its present interpretation. Putting aside all finer shades of difference, today we should call it a miracle if we were to perceive an event in the outer world which could not be explained by natural laws already known or of the same kind as those already known, but which presupposed a direct intervention of the spirit. If a man were to perceive directly a spiritual event which he could not understand and could not explain according to the strict laws of mathematics and mechanics, he would say it was miraculous. The ancient Greek could not use the term ‘miraculous’ in this sense, for to him it was obvious that everything which takes place in Nature is effected by Spirit; he did not discriminate between the daily happenings in the ordering of Nature and rarer events. The one kind occurred only rarely, the other kind was habitual, but for him spiritual creation, divine-spiritual activity, entered into every natural event. You see how these concepts have changed. For the intervention of the spirit in events on the physical plane to be regarded as miraculous is essentially a feature of our own time. It is peculiar to our modern way of looking at things to draw a sharp line between what we believe to be governed by natural law and what we have to recognise as a direct intervention of spiritual worlds.

I have spoken to you of the harmonising of two streams of culture which I may call the Demeter-Persephone stream and the Agamemnon-Iphigenia stream. It is the mission of Spiritual Science to unite these two streams. We cannot emphasise too strongly how necessary it is for humanity to learn to feel again that the spiritual is active in everyday events as well as in rarer occurrences. But this requires a clear recognition that there are two currents in human experience. Men must be quite clear that there are things which form part of a system of nature, things which follow the laws accepted today by the physicist, the chemist, the physiologist, the biologist, while on the other hand there are also other occurrences which can be accepted as facts, just as the facts which follow the physicalmathematical-chemical laws, but which cannot be explained unless one recognises the reality of a spiritual movement and life behind the physical plane.

The whole conflict caused in the human soul by this opposition between Nature and Spirit, and at the same time the longing to resolve it, is discharged in my Rosicrucian Drama The Portal of Initiation in the soul of Strader. There we see how such an event as Theodora's vision, an event outside the ordinary processes of nature, affects someone who is accustomed only to accept as valid phenomena which can be explained by the laws of physics and chemistry ... Strader's character and his inner experiences illustrate how such an event acts upon the heart as an ordeal of the soul. This scene epitomises the sense of conflict which finds expression in countless modern souls. People like Strader are very numerous today. To such people it is a necessity to inquire into the characteristics of the regular, normal course of natural events, events which can be explained by physical, chemical or biological laws; on the other hand it is also necessary that such souls should be brought to recognise other events, events which also take place on the physical plane, but which are classed as miracles by the purely materialistic mind, and hence brushed aside as impossibilities and not recognised for what they are.

Thus we can say that today there is a longing to reconcile the opposition between nature and spirit, an opposition which did not yet exist in ancient Greece. And the fact that attempts are made, that societies are established, to examine the activity and nature of laws in the physical world other than purely chemical, physiological, biological laws, is proof that the longing to resolve this opposition is very widely felt. It is part of the mission of our own Spiritual Science to resolve this opposition between spirit and nature. We must set to work out of new sources of spiritual-scientific insight; we must fit ourselves to see again in what is all around us more than meets the eye of the physicist or the chemist or the anatomist or the physiologist. To do this we must start with man himself, who so emphatically demands not only that the chemical and physical laws active in his physical body should be studied, but also that the connection between physical, psychic and spiritual, which for anyone who will look attentively can become visible in an unobtrusive way even to physical eyes, should be investigated.

The man of today no longer experiences what I have so far only been able to put before you as the working of the Demeter or the Persephone forces in the human organism. He no longer experiences the important fact that what is diffused over the whole universe without is also in us. The Greek did experience this. Even if he could not express it in modern terms, he experienced a truth, for example, of which modern theology will only slowly become convinced again—a truth which I will try to bring home to you in the following way. Today you look upwards to the rainbow. So long as it cannot be explained it is as much a wonder of Nature, a wonder of the world, a miracle, as anything else. Amid all that is familiar in everyday life there stands before our eyes the marvellous bow with its seven colours ... we will ignore all the explanations of the physicist, for the physics of the future will have quite different things to say about the rainbow too. We say to ourselves: ‘Our gaze falls upon the rainbow which emerges as if out of the bosom of the surrounding universe; in looking at it we look into the macrocosm, into the great world; the macrocosm gives birth to the rainbow.’ Now let us turn our gaze inwards; within ourselves we can observe that out of a vague, unthinking brooding, there emerge specific thoughts relating to something or other—in other words, thought flashes up within our souls. It is an everyday experience, we have only to see it in the right light. Let us take these two things, the macrocosm which gives birth to the rainbow out of the bosom of the universe, and the other thing, that in ourselves thought is born out of the rest of our soul-life. Those are the two facts of which the wise men of ancient Greece already knew something and which men will come to know again through Spiritual Science. The same forces which cause thoughts to light up in our microcosm call forth the outward rainbow from the bosom of the universe. Just as the Demeter forces from without enter into man and become active within, so outside us in the cosmos those forces are active which form the rainbow out of the ingredients of Nature; there they work spread out in space; within, in the microcosmic world of man, they cause thought to flash up out of the indefinite. Of course ordinary physics has not yet come anywhere near such truths, nevertheless, that is the truth.

Everything that is outside in space is also within us. Today man does not yet recognise the complete harmony which exists between the mysterious forces at work in himself, and the forces active outside in the macrocosm; indeed he probably regards that as a fantastic daydream. The ancient Greek could not say what I say today about these things, because he could not penetrate the matter with intellect, but it lived in his subconscious, he saw it, or felt it clairvoyantly. If today we wish to express in up-to-date phraseology what the Greek felt, we must say that he felt working within him the forces which caused thought to flash up, and felt that they were the same forces which organised the rainbow without. That is what he experienced. And he said to himself: ‘If there are psychic forces within me which cause thought to flash up, what is it that is without? What is the spiritual force in the widths of space, above and below, right and left, before and behind? What is it outspread there in space which causes the rainbow to flash up, causes the sunrise and the sunset, causes the glimmer and the glory of the clouds, just as within me the forces of the soul bring forth thought?’ For the ancient Greek it was a spiritual Being who gave birth out of the universal ether to all these phenomena—to the roseate tints of sunrise and sunset, to the rainbow, to the glimmer and the glory of the clouds, to thunder and lightning. And out of this feeling, which, as I said before, had not become intellectual knowledge, but was elemental feeling, there arose the intuitive perception, ‘That is Zeus!’ One does not get any idea, still less any sense of what the Greek soul experienced as Zeus, if one does not approach this experience and this feeling by way of the spiritual-scientific outlook. Zeus was a Being with a clearly defined form, but one could not get an idea of him without the feeling that the forces which cause thought to light up in us are also at work in what flashes up externally, such as the rainbow and so on. But today in anthroposophical circles, when we look into the human being and try to learn something of the forces which call forth in us thoughts, ideas—the forces which call forth all that flashes up in our consciousness—we say that all this constitutes what we call the astral body. In this way, having the microcosmic substance, the astral body, we can give an answer in terms of Spiritual Science to the question we have just put in a more pictorial way, and we can say that as a microcosm we have in us the astral body ... we can then ask ourselves what corresponds without in the widths of space to the astral body—what fills all space right and left, behind and before, above and below? Just as the astral body extends throughout our microcosm, so is the universal ether, so are the wide expanses of space, permeated with the macrocosmic counterpart of our astral body, and we can also say that what the ancient Greek pictured to himself as Zeus is the macrocosmic counterpart of our astral body. In us we have the astral body, it causes the phenomena of consciousness to light up; without extends the astrality from which, as from the cosmic womb, is born the rainbow, the sunrise, the sunset, thunder and lightning, clouds and snow. The man of today can find no word to cover what the Greek thought of as Zeus, and which is the cosmic counterpart of our astral body.

To continue: Besides what lights up in us momentarily or for a short time as thought, as idea, as feeling, we have our enduring life of soul, with its emotions and passions, with its fluctuating life of feeling, something which is abiding and subject to habit and memory. It is by their permanent soul-life that we recognise individuals. Here we see a man of wild passions, impetuously laying hold of everything in his path; here another who has no interest in the world. That is something quite different from the momentary thought, that is what constitutes the permanent configuration of our inner life, the basis of our happiness, of our destiny. The man of fiery temperament, of strong passions, sympathies and antipathies, may in certain circumstances commit some action which causes him happiness or unhappiness. The forces in us which represent the more enduring qualities, the qualities which turn into memory and habit, must be distinguished from the forces of the astral body—the former are rooted in our ether bodies. You know that from other lectures.

Now if we were to put the matter as a Greek would do, we should ask once more whether there is anything outside in the cosmos which has the same forces as we bear in our habits our passions, our enduring emotive attitudes. And once more the Greek felt the answer, was conscious of the answer without undergoing any intellectual process. He felt that in the ebb and flow of the ocean, in the storms and hurricanes which rage over the earth, the same forces are active as are active in us when lasting emotions, when passion and habit pulsate through our memory. When we are speaking microcosmically they are the forces in us which we cover by the term ‘ether body’, and which bring about our lasting emotions. Macrocosmically speaking they are forces more closely bound up with the earth than the forces of Zeus in the widths of space, they are the forces which determine wind and weather, storm and calm, untroubled and raging seas. In all these phenomena, in storm and tempest, in tumultuous or untroubled seas, in hurricane or doldrums, the modern man sees merely ‘nature’, and present-day meteorology is a purely physical science. For the Greeks there was as yet no such thing as a purely physical science comparable to what we have today in meteorology. To talk of meteorology in such terms he would have thought as senseless as it would be for us to investigate the physical forces which move our muscles when we laugh, if we did not know that in these movements of our muscles psychic forces are involved. To the Greeks all these things were gestures without and around us, gestures of the same spiritual activity that is revealed in us, in the microcosm, as lasting emotion, passion, memory. The ancient Greek was still conscious of a figure who could be reached by clairvoyance, he was still conscious of the ruler, the centre of all these forces in the macrocosm, and spoke of him as Poseidon.

Today we will go on to speak of the physical body, the densest part of the human being. Microcosmically speaking we have to look upon the physical body as composed of all those characteristics of the human being which have not been mentioned as belonging to the other two bodies. Everything in the nature of transitory thought and idea, thought which arises in us and then disappears, belongs to the astral body; every habitual, lasting attitude of mind, everything which is not merely thought in the sense that it leads its own isolated thought-existence in the soul, belongs to the ether body. And for everything which is not merely a sentiment, an attitude of mind, but which passes over into the sphere of will, for everything which results in an impulse to do something, man needs in this life between birth and death the physical body. The physical body is what serves to raise the mere thought or the mere sentiment to an impulse of will, it is the prime mover behind the deed in the physical world. The will-impulses, the soul-forces which lie behind the will, find their expression in the whole outward aspect of the physical body. The physical body is the expression of will-impulses as the astral body is the expression of mere thoughts, and the ether body of enduring sentiments and habits. In order that will can act through man here in the physical world he must have the physical body. In the higher worlds, activity of will is something quite different from what it is in the physical world. Thus, as microcosms, we have in us above all those forces of soul which bring about our will-impulses, impulses which are needed to make good the claim that the ego is the central governing power of the human soul. For without his will man would never attain to an ego-consciousness. Now when the Greek asked himself what it was, outspread in the macrocosm, that corresponded to the forces in us which call forth the will-impulse—the whole world of will—what did he answer? He gave it the name of Pluto. Pluto, as the central ruling power outspread in macrocosmic space, but closely associated with the solid mass of the planet, was for the Greeks the macrocosmic counterpart of the impulses of will which forced the life of Persephone into the depths of the soul.

Anyone who has clairvoyant consciousness, who can see into the real spiritual world, has a self-knowledge which can properly distinguish this threefold nature of his being into astral, etheric and physical bodies. The ancient Greek was really not in a position to examine the microcosm with the precision we apply to it today. Actually it was not until the beginning of our fifth post-Atlantean culture-epoch that man's attention was turned to the microcosm. The ancient Greek was far more conscious of the Pluto, Poseidon and Zeus forces outside him and took it for granted that those forces worked into him.

He lived far more in the macrocosm than in the microcosm. Therein lies the difference between ancient and modern times, that the Greek felt mainly the macrocosm and consequently peopled the world with the gods who were for him its central ruling powers; whereas the modern man thinks more about the microcosm, about man himself, the centre of our own world, and thus seeks more within his own being for the distinguishing features of this threefold world.

We begin to see how it was that, just at the beginning of our fifth post-Atlantean culture-epoch, there arose in all sorts of ways in western esotericism an awareness of the inner activity of the soul-forces, so that physical, etheric and astral bodies were distinguished. Now that occult investigation in this direction is being pursued with greater intensity, many things to which particular individuals in modern times have borne testimony can be confirmed today. For instance, it has been possible recently to confirm experiences which occurred in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as to the ‘clear-tasting’ of one's own being. Just as one can speak of clairvoyance, or clairaudience, so one may speak of clairsipience. This clairsipience can apply to the threefold human being, and I can describe to you the difference between external sensations of taste and the various sensations of taste which a man can have in connection with his own threefold being.

Try to imagine vividly the taste you have when you eat a very tart fruit such as the sloe, which contracts the palate; imagine this wry sensation enhanced so that you are completely permeated by the sensation of bitterness, of astringency, of downright pain; try to imagine yourself from top to bottom, right down to the finger-tips and in every limb, permeated by this astringent taste, then you have the self-knowledge which the occultist calls the self-knowledge of the physical body through the occult sense of taste, the spiritual sense of taste. When self-knowledge works in such a way that man feels himself completely permeated by this astringent taste, the occultist knows that he is experiencing knowledge of his own physical body through the occult sense of taste, for he knows that the astral body and the etheric body are bound to taste quite different, if I may so express it. As astral and etheric man, one has a different taste from what one has as physical man. These things are not said out of the blue, but out of concrete knowledge; they are known to occultists in the same way as the laws of the outside world are familiar to physicists and chemists.

Now take—not exactly the taste you get from sugar or from a sweet—but the delicate etheric sensation of taste, which most men do not experience, but which nevertheless can be experienced in physical life when, for example, you enter into an atmosphere which you enjoy very much—let us say into an avenue of trees or into a wood, where you feel, ‘Ah, how delicious it is here, I should like to be one with the scent of the trees!’ Imagine this kind of experience, which can really grow into a kind of taste, a taste which you can have when you can forget yourself in your own inwardness, when you can feel yourself so united with your surroundings that you would like to taste yourself into those surroundings ... imagine the experience transferred into the spiritual, then you have the clairsipience which the occultist knows when he seeks the self-knowledge which is possible in respect of the human ether body. It comes if one says, ‘I am now eliminating my physical body, I am shutting off everything connected with the will-impulses, I am suppressing the flashing-up of thought, and surrendering myself entirely to my permanent habits, to my sympathies and antipathies.’ When the occultist acquires the taste of this, when as a practising occultist he feels himself in this etheric body of his, then there comes to him a spiritualised form of taste rather like what I have just described as regards the physical world. Thus there is a clear distinction between self-knowledge in respect of the physical and of the etheric bodies.

The astral body can also be recognised by the occultist who has developed these higher faculties. But in this case one can no longer properly speak of a sense of taste. In the case of the astral body the sense of taste is lacking, just as it is in the case of certain physical substances. Knowledge of one's own astral body has to be described in quite different terms. But it is also possible for the practising occultist to eliminate his physical body, to eliminate his ether body, and to relate his self-knowledge solely to his astral body—that is to say, to pay attention only to what his astral body is. The normal man does not do that. The normal man experiences the interworking of physical, etheric and astral. He never has the astral body alone, he cannot experience it because he is incapable of shutting out the physical and etheric bodies. When this does happen to the practising occultist, he certainly gets at first a very unpleasant sensation ... it can only be compared with the sensation which overcomes us in the physical world when there is not enough air, when we have a feeling of breathlessness. When the etheric and physical bodies are suppressed, and self-knowledge is concentrated upon the astral body, there comes a feeling of oppression rather like breathlessness. Hence knowledge of a man's own astral body is first and formost accompanied by fear and anxiety, more so than in the other cases, because it consists basically in being filled through and through with a sense of oppression. It is impossible to perceive the astral body in isolation without becoming filled with dread. That in ordinary life we are not aware of this fear, which is there all the time, arises from the fact that the normal man, when aware of himself, feels a mixture, a harmonious or inharmonious working together of physical, etheric and astral, and not the isolated, separate members of the human being.

Now that you have heard what are the main experiences of the soul in self-knowledge as regards the physical body, which represents the Pluto forces in us, as regards the ether body, which represents the Poseidon forces, and as regards the astral body, which represents the Zeus forces, you may want to know how these forces work together; what is the relationship between the three kinds of force? Well, how do we express relationship between things and events in the physical world? It is very simple. If anyone were to give you a dish containing peas and beans and perhaps lentils all jumbled up together, that would be a mixture. If the quantities of each were not equal, you would have to separate peas, beans and lentils from one another to get the ratio between their quantities. You could say, for example, that their quantities were in the ratio of 1:3:5; in short, when you are dealing with a mixture of things, you have to find out the proportions of the component parts of the mixture. In the same way we can ask what is the ratio of the strength of the forces of the physical body to those of the etheric body, to those of the astral body? How can we express the relative magnitudes of physical, etheric and astral bodies? Is there a numerical formula, or any other formula, which can express their relative strengths? The question of this relationship will enable us to acquire a profound insight, first into the wonders of the world, and then into the ordeals of the soul and into the revelations of the spirit. We will begin to speak about it today; we shall be led further and further into the subject.

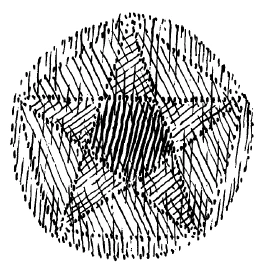

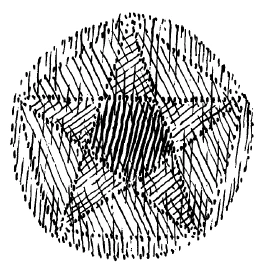

The proportions can be expressed. There is something which shows quite exactly the quantities and the strengths of our inner forces in physical, etheric and astral bodies respectively, and the corresponding relationships between them. Let me make a diagram of it for you. For these relationships can only be expressed by means of a geometrical figure. If we ponder deeply this figure we find that it contains—like an occult sign on which we can meditate—all the proportions of size and strength of the forces of physical, etheric and astral bodies respectively. You see that what I am drawing is a pentagram.

If we look at this pentagram, to begin with, taken at its face value, it is a symbol for the etheric body. But I have already said that the ether body also contains the central forces of both astral and physical bodies; it is from the ether body that all the forces, the ageing and the youth-giving forces emanate. Because the ether body is the centre for all these forces it is possible to show, in this diagram, in this sign and seal of the ether body, what in the human body is the ratio between the strength of the forces of the physical body, the strength of the forces of the etheric body, and the strength of the forces of the astral body respectively.

One arrives at the precise magnitude of these relationships in this way; within the pentagram there is an upside-down pentagon. I will fill it in completely with chalk. That gives us to start with one of the component parts of the pentagram. You get another part of the pentagram if you look at the triangles based on the sides of the pentagon. These I am shading with horizontal lines. Thus the pentagram has been reduced to a central pentagon with its point downwards (blocked out in chalk) and five triangles which I have shaded by means of horizontal lines. If you compare the size of the pentagon with the size of the sum of the five triangles, you can say, ‘as the size of this pentagon is to the size of the sum of the five triangles, so are the forces of the physical body in man to the forces of his etheric body.’ Note well that just as one can say in the case of a mixture of peas, beans and lentils that the quantity of lentils is to the quantity of beans let us say—as three to five, so we can say, ‘the ratio of the strength of the forces in the physical body is to the strength of the forces in the etheric body as the area of the pentagon in the pentagram is to the sum of the areas of the triangles which I have shaded horizontally.’ Now I will draw a pentagon with the point upwards, by circumscribing the pentagram. In this case you must not take only the triangles which complete the figure, but the whole pentagon, including the area of the pentagram—that is to say, including all that I have shaded vertically. Now consider this vertically shaded pentagon around the pentagram.

As is the area of this small downward-pointing pentagon to the area of this vertically shaded upward-pointing pentagon, so is the strength of the forces of the physical body in man to the strength of the forces of his astral body. In short, in this figure you find expressed the reciprocal relationships of the forces of physical, etheric and astral forces in man. It does not all come into human consciousness. The upward-pointing pentagon comprises all the astral forces in man, including those of which he is not yet aware, and which will be perfected as the ego transforms the astral body more and more into Spirit-Self or Manas.

Now you may wonder how these three sheaths are related to the ego. You see, normally developed man today knows very little of the real ego, which I have called the baby, and which is the least developed of the human members. But all the forces of the ego are already in man. If you want to consider the total forces of the ego in relation to the forces of physical, etheric and astral bodies, you need only describe a circle around the whole figure. I don't want to make the diagram too confusing, but if I were to shade the whole area of the circle, the ratio of the size of its area to the size of the area of the upward-pointed pentagon, to the sum of the areas of the horizontally-shaded triangles, to the small downward-pointed pentagon which I have filled in with chalk ... would give the ratio of the forces of the entire ego (represented by the area of the circle) to the forces of the astral body (represented by the area of the large pentagon), to the forces of the ether body (represented by the sum of the horizontally shaded triangles around the small pentagon), to the forces of the physical body (represented by the area of the pentagon filled in with chalk). If you give yourself in meditation to this occult sign and acquire a certain feeling for the proportional relationships of these four different areas, you get an impression of the mutual ratios of physical, etheric, astral and ego. Thus, you must think with the same attentiveness of the large circle and try to grasp it in meditation. Next you must place before you the upward- pointing pentagon, and because it is somewhat smaller than the circle—to the extent of these segments of the circle here—it makes a weaker impression upon you than the circle. And to the extent to which the impression of the pentagon is weaker than the impression of the circle, so are the forces of the astral body weaker than the forces of the ego. And if as a third exercise you place before you the five horizontally shaded triangles (without the middle pentagon) you have a still weaker impression if you are thinking with the same degree of attentiveness. And to the extent to which this impression is weaker than the impression made by the two previous figures, so are the forces of the etheric body weaker than the forces of the astral body or the forces of the ego. And if you place before you the small pentagon, assuming the same degree of attentiveness, you get the weakest impression. If you can acquire a feeling of the relative strengths of these four impressions and can retain them, as we hold together in our thought the notes of a melody—if you can think these four impressions together in proportion to their strengths, then you have the measure of harmony which exists between the forces of ego, astral, ether and physical bodies respectively.

What I have shown you is an occult sign; one can meditate on such signs; I have described more or less how it is done. By thinking of the relative sizes of these areas with an equal attentiveness, one gains an impression of their difference in strength. Then one receives a corresponding impression of the relative strengths of the forces of the four members of the human being. These things are symbols of the true occult script, emanating from the nature of things. To meditate on this script means to read the signs of the great world-wonders, which guide us into the great world-secrets. Thereby we gradually acquire a complete understanding of what is at work in the cosmos as wonders of the world, an understanding of the fact that the spirit pours itself into matter in accordance with definite ratios. I have at the same time evoked in you something of what was really the most elementary exercise of the old Pythagorean schools. A man begins by meditating on the occult signs, makes them real to himself, and then finds that he has seen the truth of the world with its wonders; then he begins to perceive with his spiritual hearing the harmonies and the melodies of the forces of the world. Tomorrow we will go further into this. My main object today has been to place before your souls this occult sign, which will lead us a step further into the nature of man.

Dritter Vortrag

In diesem Vortragszyklus hoffe ich Ihnen von einer gewissen Seite her einen Überblick über wichtige Tatsachen unserer Geisteswissenschaft geben zu können. Den Faden oder die Disposition, die dabei eingehalten werden soll, werden Sie allerdings erst in den letzten Vorträgen überschauen können, weil eine ganze Reihe von Fragen berührt werden soll, welche sich dann in den letzten Tagen zu einem Gesamtbilde zusammenschließen werden. Ich habe an den letzten zwei Abenden in manchen Dingen angeknüpft an das Mysterium von Eleusis, an die griechische Mythologie; ich werde noch öfter Gelegenheit haben, an unsere Aufführungen anzuknüpfen. Daß aber in diesem Zyklus noch ein anderes Ziel angestrebt wird, werden Sie eben am Ende erkennen. An dem heutigen Abend möchte ich in Ihnen von einer anderen Seite her ein wenig die Empfindung hervorrufen, wie Geisteswissenschaft in unserer Gegenwart hinarbeitet zu jener großen, gewaltigen Urweisheit, von der wir ein klein wenig gesehen haben, wie sie jene mächtigen Gestalten und Bilder und Mysteriennachrichten durchleuchtet, die aus dem alten Griechenland heraufkommen. Man muß sich schon einmal damit bekannt machen, meine lieben Freunde, wenn man die ganze Aufgabe und Mission der Geisteswissenschaft heute empfinden will, daß manche Vorstellung, mancher Begriff, der in unserer Gegenwart herrscht, sich verändern muß. Und in dieser Beziehung ist ja der Mensch der Gegenwart oftmals recht kurzsichtig, denkt kaum über die allernächsten Zeiten hinaus. Gerade aus diesem Grunde, um ein Gefühl hervorzurufen, wie wir unser Vorstellen, unser Denken selber ändern müssen, wenn wir so recht tief die Mission der Geisteswissenschaft überschauen wollen, wurde hingewiesen auf das ganz Andersartige der griechischen Anschauung von Welt und Leben, von dem Verhältnis des Menschen zur geistigen Welt. Denn ganz anders hat das griechische Herz, die griechische Seele gefühlt, als der moderne Mensch in dieser Beziehung fühlt. Und da möchte ich heute eines gleich im Beginn erwähnen.

Ihnen allen ist ein Begriff sehr geläufig, eine Idee, die heute ja nicht nur in unserem Wortschatz in allen Sprachen geläufig ist, sondern die auch in die Bezeichnungen einer gewissen Wissenschaftsrichtung eingeflossen ist. Es ist das Wort Natur. Und indem das Wort Natur ausgesprochen wird, entsteht gleich eine ganze Menge von Vorstellungen, welche die heutige Seele empfindet über irgend etwas, was eben als Natur bezeichnet wird. Und wir stellen Natur dann der Seele oder dem Geiste gegenüber. Nun sehen Sie, meine lieben Freunde, alles das, was der gegenwärtige Mensch meint, wenn er den Ausdruck Natur gebraucht, alles das, was wir heute als Natur bezeichnen, gab es einfach für ein altes griechisches Denken nicht. Sie müssen das ganz ausstreichen, was Sie heute mit dem Ausdruck Natur bezeichnen, wenn Sie eindringen wollen in das alte griechische Denken. Jenen Gegensatz, jene Zweiheit zwischen Natur und Geist, wie wir sie heute empfinden, das kannte der alte Grieche nicht. Wenn er sein Auge hinlenkte auf die äußeren Vorgänge, wie sie sich abspielen in Wald und Feld, in Sonne und Mond, in der Sternenwelt, dann empfand der alte Grieche noch nicht ein geistentblößtes Naturdasein, sondern ihm war alles das, was da geschah in der Welt, ebenso die Tat von geistigen Wesenheiten, wie uns die Tat, die etwa in einer Handbewegung besteht, Ausdruck ist unserer Seelentätigkeit. Wenn wir unsere Hand von links nach rechts bewegen, so wissen wir, dieser Handbewegung liegt zugrunde eine Seelentätigkeit, und wir sprechen nicht von einem Gegensatz der bloßen Bewegung der Hand und unseres Willens, sondern wir wissen, daß das eine Einheit ist, was da sich als Hand bewegt und was unser Wille als Bewegungsimpuls darstellt. Da fühlen wir noch die Einheit, wenn wir einen Gestus machen, den unsere Seele ausführt. Wenn wir unseren Blick hinauswenden zum Gang von Sonne und Mond, wenn wir die sich bewegenden Wolken sehen, wenn wir die sich bewegende Luft im Winde wahrnehmen, dann sehen wir nicht mehr so etwas, wie der alte Grieche gesehen hat, was gleichsam Handbewegungen, äußere Gesten von göttlichgeistigen Wesenheiten sind, sondern wir sehen etwas, was wir nach äußeren, abstrakten, rein mathematisch-mechanischen Gesetzen betrachten. Solch eine Natur, die nach rein äußeren, mathematisch-mechanischen Gesetzen betrachtet wird, die nicht bloß die äußere Physiognomie des göttlich-geistigen Handelns darstellt, kannte der alte Grieche nicht. Wir werden hören, wie der Begriff Natur, so wie ihn der heutige moderne Mensch hat, erst entstanden ist.

Geist und Natur waren in jenen alten Zeiten also in völligem Einklang miteinander. Daher gab es für den alten Griechen auch das noch nicht mit denselben Empfindungswerten wie heute ausgestattet, was in der heutigen Zeit ein Wunder genannt wird. Wenn wir jetzt absehen von allen feineren Unterscheidungen, so können wir heute sagen, ein Wunder würde gesehen, wenn ein Vorgang in der Außenwelt wahrgenommen würde, der nicht nach den bereits bekannten oder mit ihnen verwandten Naturgesetzen erklärbar ist, sondern der voraussetzt, daß der Geist unmittelbar eingreift. Da wo der Mensch wahrnehmen würde ein unmittelbar Geistiges, was er nicht bloß nach rein äußerlichen, mathematisch-mechanischen Gesetzen begreifen und erklären kann, würde er von etwas Wunderbarem sprechen. In diesem Sinne konnte der alte Grieche nicht von etwas Wunderbarem sprechen. Denn ihm war klar, daß der Geist alles macht, was in der Natur geschieht, ob es nun die alltäglichen, in unsere Naturordnung sich einfügenden Ereignisse waren oder seltenere Naturzusammenhänge, das machte keinen Unterschied. Das eine war nur seltener, das andere war das Gewöhnliche, aber der Geist, das göttlich-geistige Schaffen und göttlich-geistige Wirken, griff ihm in alles Naturgeschehen ein. So sehen Sie, wie sich diese Begriffe geändert haben. Daher ist es auch etwas wesentlich unserer Gegenwart Angehöriges, daß das geistige Eingreifen in die äußeren Ereignisse des physischen Planes wie etwas Wunderbares empfunden wird, wie etwas, was herausfällt aus dem gewöhnlichen Gang der Ereignisse. Es ist nur unserer modernen Empfindung eigen, eine scharfe Grenze zu ziehen zwischen dem, was man von Naturgesetzen beherrscht glaubt, und dem, wo man ein unmittelbares Eingreifen der geistigen Welten anerkennen muß.

Ich habe Ihnen von dem Zusammenklingen zweier Strömungen gesprochen, der Demeter-Persephone-Strömung und der, wenn ich so sagen darf, Agamemnon-Iphigenie-Strömung. Sie sollen verbunden werden durch die Mission der Geisteswissenschaft. Wir könnten auch noch, anknüpfend an diese Vereinigung der beiden Strömungen, von der Notwendigkeit sprechen, daß die Menschheit wiederum empfinden lernt, daß überall bei den alltäglichen und bei den selteneren Vorkommnissen das Geistige wirksam ist. Dazu aber ist notwendig, daß das, was der moderne Mensch als zwei Strömungen empfindet, auch vor seine Seele tritt, daß er sich klarmacht: Hier habe ich auf der einen Seite diejenigen Dinge, die sich einfügen als ein Natursystem in die Gesetze, die heute der Physiker, der Chemiker, der Physiologe, der Biologe anerkennt, und hier habe ich auf der anderen Seite Vorkommnisse, die einfach als Tatsachen ebenso verfolgt werden können wie andere Tatsachen, die sich eben in die physischen, mathematisch-chemischen Gesetze einfügen, die aber nicht erklärt werden können, wenn man nicht ein geistiges Weben und Leben hinter dem physischen Plan als eine Realität anerkennt.

Den ganzen Konflikt, der durch diesen Zwiespalt und zu gleicher Zeit durch die Sehnsucht nach Vereinigung der beiden Gegensätze Natur und Geist in der menschlichen Seele hervorgerufen wird, sehen Sie im Rosenkreuzerdrama abgeladen in der Seele des Strader. Und wie ein aus dem gewöhnlichen Naturgange herausfallendes Ereignis, wie die Offenbarung der Theodora, auf denjenigen wirkt, der gewohnt ist, nur gelten zu lassen, was unter die physikalischen und chemischen Gesetze fallen kann, wie das auf das Gemüt wie eine Prüfung der Seele wirkt, sehen Sie auch am Charakter und an den Geschehnissen der Seele des Strader dargestellt in dem Rosenkreuzermysterium «Die Pforte der Einweihung». Damit haben Sie aber nur gleichsam herauskristallisiert etwas, was als die Empfindung dieses Gegensatzes in zahlreichen modernen Seelen sich ausdrückt. Diese Straderseelen sind sehr häufig in der heutigen Zeit. Für solche Straderseelen ist es notwendig, daß sie auf der einen Seite das Eigentümliche des regulären, des normalen Ganges der Naturtatsachen, die durch die physikalischen, chemischen, biologischen Gesetze erklärt werden können, einsehen. Auf der anderen Seite ist es aber auch notwendig, daß solche Seelen hingeführt werden zur Anerkennung jener Tatsachen, die auch auf dem physischen Plane auftreten, aber von dem rein materialistischen Sinn als Wunder und daher als etwas Unmögliches einfach liegengelassen und nicht anerkannt werden.

Ich habe ja schon in anderen Zusammenhängen erwähnt, daß sich das Verdienst, auf solche Tatsachen in schönem Zusammenhang hingewiesen zu haben in einer Weise, wie es eben gerade für die gegenwärtige theosophische Bewegung notwendig ist, unser Freund Ludwig Deinhard erworben hat. Sie werden in dem ersten Teile seines Buches «Das Mysterium des Menschen» gerade diese Seite des modernen Lebens und den richtigen Hinweis auf die Tatsachen innerhalb des physischen Planes und ihren Hintergrund in der geistigen Welt sehen, Sie werden sehen, wie der moderne Geist diese durchaus absolut für unsere Bewegung notwendige Seite in Erwägung und Berücksichtigung ziehen kann. Insofern ist es von ganz besonderer Wichtigkeit, daß wir dieses Buch jetzt haben, das namentlich auch in den Händen aller Freunde nützlich und zielvoll wirken kann, weil diese Gelegenheit finden können, den außenstehenden Seelen, die noch einen anderen Zugang brauchen als diejenigen, die schon die esoterische Sehnsucht fühlen, einen Weg zu eröffnen herein in das spirituelle Leben. Und da in diesem Buche ein richtiger Einklang versucht wird zwischen diesem einen Weg des modernen wissenschaftlichen Denkens und unserer Esoterik, so ist dieses Buch in den Händen der Freunde ein vorzügliches Mittel, der Geisteswissenschaft gerade in unserer Gegenwart zu dienen.

So können wir also sagen, Sehnsucht ist heute vorhanden, jenen Gegensatz, den es im alten griechischen Lande noch nicht gab zwischen Natur und Geist, auszugleichen. Und daß Versuche gemacht werden - Sie finden ja diese Versuche auch in dem genannten Buche dargestellt —, daß Gesellschaften gegründet werden, die das Weben und Wesen anderer Gesetze in der physischen Welt verfolgen als der rein chemischen, physiologischen, biologischen, das ist ein Beweis dafür, daß in weitesten Kreisen die Sehnsucht empfunden wird, diesen Gegensatz zu überbrücken. Es liegt also die Überbrückung, die Harmonisierung des Gegensatzes zwischen Geist und Natur innerhalb der Mission unserer geisteswissenschaftlichen Wirksamkeit. Wir müssen sozusagen herausarbeiten aus neuen Quellen geisteswissenschaftlicher Anschauung, müssen wiederum in die Lage kommen, in demjenigen, was uns umgibt, mehr zu sehen als das, was das Auge des Physikers oder Chemikers oder des Anatomen oder des Physiologen oder des Biologen sieht. Dazu müssen wir in der Tat ausgehen von dem Menschen selber, der ja so sehr herausfordert, nicht nur die im physischen Leibe wirksamen chemischen und physikalischen Gesetze zu studieren, sondern das Zusammenwirken aufzusuchen von Physischem, Seelischem und Geistigem, das überall für den aufmerksamen Beobachter vor das geistige Auge und vielfach in deutlichster Weise auch vor die äußeren Augen treten kann.

Der moderne Mensch empfindet nun nicht mehr das, was ich Ihnen bisher nur andeuten konnte als das Hereinwirken der Demeterkraft oder Persephonekraft in den menschlichen Organismus. Er empfindet nicht mehr die große Tatsache, daß wir in uns alles das tragen, was draußen im Weltenall ausgegossen ist. Der Grieche empfand das. Er empfand, wenn er es auch nicht in unserem modernen Sinn hätte aussprechen können, zum Beispiel eine Wahrheit, von welcher sich die moderne Geisteswissenschaft langsam erst wiederum überzeugen wird - eine Wahrheit, die ich Ihnen etwa in folgender Art nahebringen möchte. Sie wenden heute den Blick hinauf zum Regenbogen. Solange man ihn nicht erklären kann, ist er ebenso ein Naturwunder, ein Weltenwunder wie etwas anderes. Da tritt uns aus der Alltäglichkeit heraus der wunderbare Bogen mit seinen sieben Farben vor Augen. Wir sehen jetzt ab von aller physikalischen Erklärung, denn die Physik der Zukunft wird noch ganz andere Dinge auch über den Regenbogen zu sagen haben als die heutige. Wir sagen, da draußen fällt unser Blick auf den Regenbogen, der wie aus dem Schoß des uns umgebenden Universums auftritt. Da schauen wir in den Makrokosmos, in die große Welt hinein. Aus ihr heraus gebiert sich der Regenbogen. Jetzt wenden wir den Blick ein wenig nach innen. In unserm Innern können wir die Bemerkung machen - sie ist eine ganz alltägliche Bemerkung, wir müssen sie nur in das richtige Licht setzen -, daß sich zum Beispiel aus dem gedankenlosen Brüten bestimmte Gedanken, die zu irgend etwas Bezug haben, herausbilden, daß mit anderen Worten der Gedanke aufblitzt in unserer Seele. Nehmen wir diese beiden Sachen: die Tatsache des Makrokosmos, daß der Regenbogen aus dem Schoße des Universums sich heraus gebiert, und die andere, daß sich in uns selber der Gedanke heraus gebiert aus unserem anderen Seelenleben. Das sind zwei Tatsachen, von denen die Weisen des alten Griechenlandes schon etwas gewußt haben, was durch die Geisteswissenschaft die Menschen wiederum lernen werden. Dieselben Kräfte, die in unserem Mikrokosmischen den Gedanken aufblitzen lassen, sind die Kräfte, die da draußen im Schoße des Universums den Regenbogen hervorrufen. Wie die Demeterkräfte von draußen in den Menschen hineinziehen und darinnen wirksam werden, so sind es die Kräfte, die draußen den Regenbogen formen aus den Ingredienzien der Natur - da würden sie ausgebreitet im Raume wirken -, die in uns drinnen mikrokosmisch, in der kleinen Welt des Menschen wirken; da lassen sie aufblitzen aus dem Unbestimmten den Gedanken. An solche Wahrheiten streift allerdings heute noch nicht eine äußere Physik, dennoch ist das in der Tat eine Wahrheit.

Alles, was da draußen im Raum ist, ist in uns selber. Der Mensch erkennt heute noch nicht den völligen Einklang der in ihm selber geheimnisvoll wirkenden Kräfte und der draußen im Makrokosmos wirksamen Kräfte, ja, er sieht das vielleicht als eine Träumerei, als eine Phantasterei an. Der alte Grieche konnte das nicht sagen, was ich jetzt gesagt habe über diese Dinge, weil er nicht mit intellektueller Kultur diese Dinge durchdrang, aber es lebte in seinem unterbewußten Seelenleben, er sah oder fühlte das hellseherisch. Und wenn wir dieses Gefühl jetzt in unseren gegenwärtigen modernen Worten ausdrücken wollen, so müssen wir sagen: Der alte Grieche fühlte, daß da in seinem Innern zum Beispiel die Kräfte wirkten, die den Gedanken aufblitzen ließen, und daß das dieselben Kräfte waren, die da draußen den Regenbogen organisieren. - Das empfand er. Er fragte sich nun: Wenn da drinnen die Seelenkräfte sind, die den Gedanken aufblitzen lassen, was ist es denn draußen, was ist in den Raumesweiten Geistiges verbreitet: oben und unten, rechts und links, vorne und hinten? Was ist da ausgebreitet im ganzen Raum? So wie die Seelenkräfte im Innern sind, wie sie drinnen den Gedanken aufblitzen lassen, wie sie draußen den Regenbogen aufblitzen lassen, die Morgen- und die Abendröte, den Glanz und Schein der Wolken, — was ist es da draußen im Raum? - Oh, da war es für den alten Griechen ein geistiges Wesen, das herausgebar aus dem gesamten universellen Äther alle diese Erscheinungen, die Morgen- und Abendröte, den Regenbogen, den Glanz und Schein der Wolken, den Blitz und Donner. Und aus diesem Gefühl, das, wie gesagt, nicht intellektuelle Erkenntnis geworden ist, sondern elementarisches Gefühl war, da entstand die Anschauung: Das ist Zeus. - Und man bekommt keine Vorstellung und noch weniger eine Empfindung von dem, was die griechische Seele als Zeus empfand, wenn man sich nicht auf dem Wege unserer geisteswissenschaftlichen Anschauungsweise dieser Empfindung und diesem Gefühle nähert. Zeus war ein unmittelbar fest gestaltetes Wesen, aber man konnte es sich nicht vorstellen, wenn man nicht ein Gefühl hatte, daß die Kräfte, die in uns den Gedanken aufblitzen lassen, auch im äußeren Blitze wie im Regenbogen und so weiter wirken. Wir aber sagen heute auf anthroposophischem Boden, wenn wir in den Menschen hineinschauen und uns von den Kräften unterrichten wollen, welche in uns so etwas hervorrufen wie den Gedanken, wie die Vorstellung, wie alles das, was da aufleuchtet und aufblitzt innerhalb unseres Bewußtseins: Alles das umfaßt, was wir den menschlichen Astralleib nennen. — Und da haben wir das Mikrokosmisch-Substantielle, den Astralleib, und können nun die Frage, die wir eben aufgeworfen haben in bildlicher Form, in einer mehr geisteswissenschaftlichen Form aufwerfen und können sagen: Mikrokosmisch ist der astralische Leib in uns. Was entspricht dem astralischen Leib in den Raumesweiten draußen, was erfüllt alle Räume, rechts und links, vorne und hinten, oben und unten? Gerade so wie der astralische Leib in unserem Mikrokosmos ausgebreitet ist, so sind die Raumesweiten, so ist der universelle Äther durchzogen vom makrokosmischen Gegenbilde unseres astralischen Leibes. Und wir können auch sagen: Das, was der alte Grieche unter Zeus sich vorstellte, ist das makrokosmische Gegenbild unseres astralischen Leibes. In uns ist der astralische Leib, er bewirkt das Aufleuchten der Erscheinungen des Bewußtseins. Außer uns ist die Astralität ausgebreitet, die aus sich heraus wie aus dem Weltenschoß gebiert den Regenbogen, die Morgen- und die Abendröte, den Blitz und Donner, Wolken, Schnee und so weiter. Der heutige Mensch hat nicht einmal eine Wortbezeichnung für das, was der alte Grieche sich unter Zeus dachte und was das makrokosmische Gegenbild unseres astralischen Leibes ist.

Nun fragen wir weiter. Wir haben außer dem, daß in uns aufleuchtet im Innern der Gedanke, die Vorstellung, das Gefühl, insofern es einen Augenblick oder kurze Zeit andauert, unser fortlaufendes Seelenleben mit seinen Leidenschaften, Affekten, mit dem auf- und abwogenden Gefühlsleben, die uns bleibend sind, die gewohnheits- und gedächtnismäßig werden. Wir haben dieses unser Seelenleben so, daß wir nach diesem Seelenleben die einzelnen Menschencharaktere unterscheiden. Da steht ein Mensch vor uns mit stürmischen Leidenschaften, die feurig ergreifen alles, was ihnen entgegentritt; ein anderer Mensch, der apathisch der Welt gegenübersteht. Das ist etwas anderes als der augenblicklich auftauchende Gedanke, das ist etwas, was die bleibende Konfiguration unseres Seelenlebens ausmacht, was ausmacht die Grundlagen unseres Glückes, unseres Schicksals. Der Mensch, der ein feuriges Temperament, der lebendige Leidenschaften, Sympathien und Antipathien hat, kann unter Umständen durch die auf- und abwogenden Bewegungen dieser Sympathien und Antipathien dieses oder jenes bewirken zu seinem Glück oder Unglück. Die Kräfte, die da in uns selber sind, die dieses mehr Bleibende, Durchgängige, zu Gedächtnis und Gewohnheit Werdende bedeuten, sind etwas anderes als die Kräfte des astralischen Leibes. Diese Kräfte sind in uns schon an den Äther- oder Lebensleib gebunden; Sie wissen das aus anderen Vorträgen. Wenn wir nun aber griechisch empfinden würden, so würden wir jetzt wiederum fragen: Gibt es da draußen im Universum irgend etwas, was dieselben Kräfte sind wie das in unseren Gewohnheiten, Leidenschaften, bleibenden Affekten Wirkende? - Und der Grieche fühlte das wiederum, ohne daß er es sich intellektualisiert, exemplifiziert zum Bewußtsein brachte. Der Grieche fühlte, daß in dem auf- und abwogenden Meere und im Sturme, Orkane, der über die Erde braust, dieselben Kräfte wirksam sind wie in uns, wenn der bleibende Affekt, die Leidenschaft, die Gewohnheit, das Gedächtnis pulsieren. Mikrokosmisch sind es die Seelenkräfte in uns, die wir unter den Begriff des Ätherleibes zusammenfassen, der unsere bleibenden Affekte und so weiter bewirkt. Makrokosmisch sind es die Kräfte, die enger an unsere Erde gebunden sind als die durch die Raumesweiten gehenden Zeuskräfte, sind es die Kräfte, welche Wind und Wetter, Sturm und Windstille, stilles und aufbrausendes Meer bewirken. In allen diesen Erscheinungen, die ich eben genannt habe, Sturm und Wetter, aufbrausendes Meer und Meeresstille, Orkan und Windstille und so weiter, sieht der heutige Mensch eben nur Natur, und die heutige Meteorologie ist eine rein äußere physikalische Wissenschaft. Solch eine rein physikalische Wissenschaft, wie wir sie heute in der Meteorologie haben, gab es noch nicht für den alten Griechen. Für den Griechen wäre es ebenso widersinnig gewesen, von einer solchen Meteorologie zu sprechen, wie es für uns widersinnig wäre, wenn wir bloß untersuchen würden, welche physischen Kräfte unsere Muskeln bewegen, wenn wir lachen, und wenn wir nicht wüßten, daß sich in diese Muskelbewegungen ergießen die seelensubstantiellen Kräfte. Das waren Gesten, geistige Wirksamkeit. Sturm und Orkan, Wind und Wetter waren Gesten, die nur draußen ausgebreitet sind, aber derselben geistigen Wirkung entsprechend, die sich in uns im Mikrokosmos als dauernde Affekte, Leidenschaften, Gedächtnis zeigte. Und der alte Grieche, der wesenhaft noch ein Bewußtsein hatte von der durch das Hellsehen erreichbaren Gestalt, von dem Regenten der Zentralgewalt dieser Kräfte im Makrokosmos, sprach das an unter dem Namen des Poseidon.

Und wir sprechen ferner heute von dem physischen Menschenleib als dem dichtesten Glied der menschlichen Wesenheit. Wir haben wiederum mikrokosmisch in dem physischen Menschenleib alles das in uns zu sehen, was der Sphäre angehört, die eben unter den beiden anderen Dingen nicht angeführt worden ist. An den astralischen Leib ist gebunden alles das, was an vorübergehenden Gedanken und Vorstellungen in uns liegt, wie sie auftauchen und verschwinden; an den Ätherleib alles das, was an gewohnheitsmäBigen, bleibenden Affekten auftritt in der menschlichen Natur, das, was nicht nur Gedanke ist, das, was also nicht in der Seele ein abgeschlossenes gedankenhaftes Dasein führt. Für das, was auch nicht bloß Affekt ist, sondern was übergeht zum Willensimpuls, zu dem Impuls, etwas auszuführen, dazu ist notwendig für den Menschen dieses Erdendaseins innerhalb von Geburt und Tod der physische Leib. Der physische Leib ist alles das, was erhebt den bloßen Gedanken oder auch den bloßen Affekt zum Willensimpuls, der der Tat in der physischen Welt zunächst zugrunde liegt. Sprechen wir also von Willensimpulsen, von den Seelenkräften in uns, die den Willensimpulsen zugrunde liegen, und fragen wir: Was drückt äußerlich aus diese Seelenkräfte, die als Wille angesprochen werden? — so haben wir das in der ganzen Physiognomie des physischen Leibes vor uns. Der physische Leib ist der Ausdruck der Willensimpulse, wie der Astralleib der Ausdruck der bloßen Gedanken und der Ätherleib der Ausdruck der bleibenden Affekte und Gewohnheiten ist. Damit der Wille durch den Menschen wirken kann hier in der physischen Welt, muß der Mensch den physischen Leib haben. In den höheren Welten ist Willenswirkung etwas ganz anderes als hier in der physischen Welt. So haben wir mikrokosmisch wieder in uns die Seelenkräfte, welche vorzugsweise die Willensimpulse bewirken, die notwendig sind für den Menschen, damit er das Ich überhaupt als die Zentralgewalt seiner Seelenkräfte ansprechen kann. Denn ohne daß der Mensch einen Willen hätte, würde er niemals zu einem Ich-Bewußtsein kommen. Wir können nun wiederum fragen - jetzt von einem anderen Gesichtspunkte als gestern -, was fühlte der Grieche, wenn er sich fragte: Was liegt da draußen ausgebreitet im Makrokosmos als dieselben Kräfte, die in uns den Willensimpuls, die ganze Willenswelt hervorrufen? Was liegt da draußen? Da antwortete er mit dem Namen Pluto. Pluto als diejenige Zentralgewalt draußen im makrokosmischen Raum, eng gebunden an den festgeballten Planeten, das war für den Griechen das makrokosmische Gegenbild der Willensimpulse, die hinunterdrängten das Persephoneleben in die Untergründe auch des Seelenlebens.

Für ein hellseherisches Bewußtsein, für ein Hineinschauen in die wirkliche geistige Welt spezifiziert sich die Selbsterkenntnis des Menschen so, daß er wohl unterscheiden kann diese dreifache Natur seiner Wesenheit nach astralischem Leib, nach Ätherleib, nach physischem Leib. Der alte Grieche war überhaupt nicht in derselben Art darauf aus, genau den Mikrokosmos ins Auge zu fassen, wie wir das heute tun. Der Blick wurde auf den Mikrokosmos im Grunde genommen erst im Beginne unserer fünften nachatlantischen Kulturepoche gerichtet. Der alte Grieche hatte vielmehr im Auge die Pluto-, die Poseidon-, die Zeuskräfte draußen und fand es selbstverständlich, daß die in ihn hineinwirkten. Er lebte viel mehr im Makrokosmos als im Mikrokosmos. Dadurch unterscheidet sich die alte Zeit von der neueren, daß der Grieche mehr das Makrokosmische empfand und daher die Welt mit seinen Göttergestalten besetzte, die ihm die Zentralgewalten der entsprechenden makrokosmischen Kräfte waren, daß aber der moderne Mensch mehr auf den Mikrokosmos, auf das Mittelpunktswesen unserer Welt, auf den Menschen bedacht ist und daher mehr in seinem eigenen Wesen die Eigentümlichkeiten der dreifach gestalteten Welt sucht. So erleben wir denn die eigentümliche Tatsache, daß aus der abendländischen Esoterik heraus in der mannigfaltigsten Art gerade am Beginne unserer fünften nachatlantischen Kulturepoche das Bewußtsein auftritt von der inneren Wirksamkeit der Seelenkräfte, so daß sie die menschliche Wesenheit nach physischem Leib, Ätherleib und astralischem Leib spezifiziert.

Und vieles von dem, was bei den einzelnen Geistern der neueren Zeit in dieser Hinsicht aufgetreten ist, kann heute, wo die okkulten Forschungen nach dieser mikrokosmischen Seite wiederum vertieft werden, neuerdings bestätigt werden. So kann namentlich voll bestätigt werden, was auftaucht im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert über das Hellschmecken der eigenen Wesenheit. Gerade so, wie man von einem Hellsehen, von einem Hellhören reden kann, so kann man auch von einem Hellschmecken reden. Und dieses Hellschmecken kann sich auf die dreifache menschliche Wesenheit beziehen, und ich kann Ihnen einen Vergleich bilden zwischen äußeren Geschmacksempfindungen und den verschiedenen Geschmacksempfindungen, die der Mensch haben kann gegenüber seiner dreifachen eigenen Wesenheit.

Stellen Sie sich einmal lebendig, ganz lebendig vor jenen Geschmack, den Sie bei einer recht herb schmeckenden Frucht empfinden, etwa bei der Schlehe, die zusammenzieht im Mund. Denken Sie sich diese Empfindung gesteigert, und denken Sie sich jetzt einmal von dieser Empfindung des Herben, des Zusammenziehenden, des sich förmlich Zusammenquälenden ganz im Innern durchdrungen, denken Sie, Sie würden in sich selber von oben bis unten durch die Finger und alle Glieder Ihres ganzen Organismus hindurch so empfinden, durchsetzt von einem zusammenziehenden Geschmack, dann hätten Sie jene Selbsterkenntnis, die der Okkultist nennen muß die Selbsterkenntnis des physischen Menschenleibes durch den okkulten Geschmackssinn, den geistigen Geschmackssinn. Wo die Selbsterkenntnis so wirkt, daß man sich selber ganz durchzogen fühlt von diesem zusammenziehenden Geschmack, da weiß der Okkultist, daß er vor der Selbsterkenntnis des physischen Leibes steht, denn er weiß, daß der Ätherleib und der astralische Leib anders schmecken müssen, wenn man so sagen darf. Man schmeckt sich anders als astralischer und als Äthermensch denn als physischer Mensch. Diese Dinge sind nicht aus dem Blauen heraus gesprochen, sondern aus konkreten Erkenntnissen heraus, die ebenso unter denen verbreitet sind, die die okkulte Wissenschaft kennen, wie die äußeren Gesetze unter den Physikern und Chemikern verbreitet sind.

Nehmen Sie jetzt jenen Geschmack, den Ihnen nicht gerade der Zucker gibt oder ein Bonbon, sondern nehmen Sie jene feine ätherische Geschmacksempfindung, die die meisten Menschen nicht empfinden, die aber doch im physischen Leben empfunden werden kann, wenn Sie etwa in eine solche Atmosphäre eintreten, in der Sie recht gerne sind, sagen wir, in eine Baumallee oder in einen Wald, wo Sie sich so fühlen, daß Sie sagen: Ach, hier bin ich eigentlich gerne, denn ich möchte, daß mein ganzes Wesen eins wäre mit all dem, was die Bäume ausduften. -— Denken Sie sich jene Art von Empfindung, die wirklich bis zu einer Art von Geschmacksempfindung sich steigern kann, die Sie haben können, wenn Sie sich selbst vergessen in Ihrer Innerlichkeit und sich so eins fühlen mit Ihrer Umgebung, daß Sie sich hineinschmecken wollten in Ihre Umgebung. Denken Sie sich diese Empfindung ins Geistige umgesetzt, dann haben Sie jene Hellempfindung, jenes Hellschmecken, das der Okkultist kennt, wenn er die Selbsterkenntnis sucht, die für den Ätherleib des Menschen möglich ist. Sie entsteht, wenn man sagt: Ich schalte jetzt meinen physischen Leib aus, alles das, was mit Willensimpulsen zusammenhängt, schalte aus auch das, was an Gedanken aufblitzt, und gebe mich nur dem hin, was die bleibenden Gewohnheiten, Affekte, Leidenschaften sind, was meine Sympathie- und Antipathienatur ist. Wenn der Okkultist das als Hellgeschmack aufnimmt, wenn er sich fühlt als praktischer Okkultist in diesem seinem Ätherleibe, dann tritt der Hellgeschmack in der Form auf, nur vergeistigt, wie ich es Ihnen eben jetzt für die physische Welt beschrieben habe. So daß genau zu unterscheiden ist die Selbsterkenntnis des physischen und die des Ätherleibes.

Der astralische Leib kann auch in dieser Weise von dem praktischen Okkultisten, das heißt von dem hellempfindenden, hellwahrnehmenden Okkultisten, erkannt werden. Aber man kann da nicht eigentlich mehr von einer Geschmacksempfindung sprechen. Sie versagt, wie ja die physische Geschmacksempfindung gegenüber gewissen Substanzen auch versagt. Wir müssen das schon anders charakterisieren, was Selbsterkenntnis des astralischen Leibes ist. Aber auch das ist möglich, daß der praktische Okkultist ausschaltet seinen physischen Leib, ausschaltet seinen Ätherleib, und daß er die Selbsterkenntnis lediglich auf seinen Astralleib bezieht, das heißt, daß er nur das berücksichtigt in sich, was sein astralischer Leib ist. Das tut der gewöhnliche Mensch nicht. Wenn dieser sich empfindet, so empfindet er ja das Zusammenwirken von physischem, Äther- und astralischem Leib. Er hat nie den physischen Leib und den Ätherleib ausgeschaltet und den astralischen Leib allein. Den kann der gewöhnliche Mensch nicht empfinden, weil er nicht ausschalten kann den physischen und den Ätherleib. Wenn das im praktischen Okkultismus geschieht, dann kommt allerdings zunächst eine wenig erfreuliche Empfindung zustande, eine Empfindung, die sich nur vergleichen läßt etwa mit der Empfindung, die die Seele in der physischen Welt überkommt, wenn wir zu wenig Luft haben, wenn wir Atemnot haben. Eine beängstigende, an Atemnot erinnernde Empfindung kommt zustande, wenn ausgeschaltet werden Ätherleib und physischer Leib und die Selbsterkenntnis bezogen wird auf den astralischen Leib. Daher ist die Selbsterkenntnis in bezug auf das Astralische zunächst in einer gewissen Weise die am meisten auch mit Furcht und Angst begleitete, weil sie im Grunde genommen in einer Art von Durchdrungensein mit Beängstigung besteht. Wir können gleichsam in Reinkultur den astralischen Leib gar nicht wahrnehmen, ohne uns zu durchängstigen. Daß wir dieses ständig in uns vorhandene Durchängstigtsein im gewöhnlichen praktischen Leben nicht berücksichtigen, rührt davon her, daß der gewöhnliche Mensch eben, wenn er sich selbst empfindet, ein Gemisch, ein harmonisches oder auch disharmonisches Zusammenwirken von physischem, Äther- und astralischem Leib wahrnimmt und nicht die einzelnen Glieder der menschlichen Wesenheit allein.

Es könnten Ihnen jetzt, nachdem Sie sogar gehört haben, welches die Grundempfindungen sind, die in der Seele auftreten als Selbsterkenntnis sowohl dem physischen Leib gegenüber, der in uns die Plutokräfte repräsentiert, als auch dem Ätherleib gegenüber, der in uns die Poseidonkräfte repräsentiert, und dem astralischen Leib gegenüber, der in uns die Zeuskräfte repräsentiert, die Fragen entstehen: Wie wirken diese einzelnen Kräfte zusammen? Welches ist das Verhältnis zwischen den drei Kräften oder Kräftearten des physischen, Äther- und astralischen Leibes? - Wie kommen wir denn zu einem Verhältnis, das wir ausdrücken wollen von Dingen und Vorgängen in der Welt? Höchst einfach! Wenn Ihnen irgendwo jemand etwas gibt, was Erbsen und Bohnen enthalten würde und vielleicht auch Linsen darunter, das bunt durcheinandergemischt wäre, so würden Sie da eine Mischung haben. Wenn diese einzelnen Quantitäten nicht gleich wären, so müßten Sie sie voneinander sondern und bekämen dann ein Verhältnis von den Quantitäten der Bohnen, Erbsen und Linsen. Sie könnten sagen, daß die Menge der Bohnen zu der Menge der Erbsen und der der Linsen sich verhält, sagen wir, wie 1:3:5 oder auch anders, kurzum, wo Sie es mit einem Gemisch zu tun haben, da können Sie veranlaßt sein, das Verhältnis in den zusammenwirkenden Dingen oder durcheinandergemischten Dingen zu untersuchen. So können Ihnen auch die Fragen in die Seele hereindringen: Wie verhält sich die Stärke der Kräfte des physischen Leibes zu der der Kräfte des Ätherleibes und der der Kräfte des astralischen Leibes in uns? Wodurch können wir ausdrücken, was da stark, was schwach ist, welches das Maß des physischen Leibes, das Maß des Ätherleibes, das Maß des Astralleibes ist? Gibt es eine Formel in Zahlen oder sonstige Mittel, wodurch wir die Verhältnisse der Kräftestärken des physischen Leibes, des Ätherleibes und des Astralleibes ausdrücken können? Über dieses Verhältnis, das uns tief hineinblicken läßt sowohl in die Weltenwunder wie später in die Seelenprüfungen und Geistesoffenbarungen, wollen wir heute erst zu sprechen beginnen. Es wird uns immer tiefer und tiefer hineinführen; dieses Verhältnis kann man ausdrücken. Man kann etwas angeben, welches ganz genau die Quantitäten und die Stärken unserer inneren Kräfte im physischen Leibe, im Ätherleibe und Astralleibe angibt und ihr entsprechendes Zusammenwirken. Und dieses Verhältnis möchte ich Ihnen zunächst auf die Tafel zeichnen. Denn es läßt sich nur in einer geometrischen Figur und ihren Größenverhältnissen zum Ausdrucke bringen. Was ich hiermit auf die Tafel zeichne, das ist so, daß wir davon sagen müssen: Wenn man sich hineinvertieft in diese Figur, so gibt alles, was in ihr enthalten ist - wie ein Zeichen der okkulten Schrift für die Meditation -, die Größen- und Stärkeverhältnisse der Kräfte unseres physischen Leibes, unseres Ätherleibes und unseres Astralleibes. Und dieses Zeichen der okkulten Schrift ist das folgende:

Sie sehen, ich zeichne das Pentagramm. Wenn wir dieses Pentagramm zunächst ins Auge fassen, so ist es uns ein Zeichen für den Ätherleib, wenn wir die Sache äußerlich nehmen. Aber ich habe schon gesagt, daß dieser Ätherleib auch die Mittelpunktskräfte für den Astralleib und den physischen Leib enthält, daß von ihm alle die Kräfte, die uns alt und jung werden lassen, ausgehen. Weil nun im Ätherleib die Mitte sozusagen für alle diese Kräfte liegt, so ist es auch möglich, an der Figur des Ätherleibes, an dem Siegel des Ätherleibes zu zeigen, welche Stärkeverhältnisse die physischen Kräfte, die Kräfte des physischen Leibes zu den ätherischen Kräften, den Kräften des Ätherleibes und zu den astralischen, den Kräften des Astralleibes, im Menschen haben. Und man bekommt ganz genau die Größenverhältnisse heraus, wenn man sich zunächst sagt: Hier im Innern des Pentagramms entsteht ein nach unten geneigtes Fünfeck. Dieses Fünfeck fülle ich mit der Kreidesubstanz vollständig aus. Da haben Sie zunächst eine der Teilfiguren des Pentagrammes. Ein anderes Stück der Teilfigur des Pentagrammes bekommen Sie, wenn Sie ins Auge fassen die Dreiecke, die sich an das Fünfeck ansetzen und die ich mit horizontalen Linien schraffiere. So habe ich Ihnen das Pentagramm hier zerlegt in ein mittleres Fünfeck mit der Spitze nach unten, das ich ausgefüllt habe mit der Kreidesubstanz, und in fünf Dreiecke, welche ich mit horizontalen Strichen schraffiert habe. Wenn Sie die Größe dieses Fünfeckes in Verhältnis bringen zu der Größe der Dreiecke, das heißt zu der Summe aller Flächen, die von den Dreiecken eingenommen werden, wenn Sie sich also sagen, wie die Größe dieses Fünfeckes zur Größe der einzelnen Dreiecke wirkt, wenn Sie die Summe der Flächen der einzelnen Dreiecke nehmen, so wirken die Kräfte des physischen Leibes zu den Kräften des Ätherleibes im Menschen. Also wohlgemerkt, wie man sagen kann, wenn Linsen und Bohnen und Erbsen zusammengemischt sind, daß die Menge der Linsen zu der Menge der Bohnen sich verhält wie drei zu fünf, so kann man sagen: Die Stärke der Kräfte im physischen Leibe verhält sich zu den Kräften des Ätherleibes wie im Pentagramm die Fläche des Fünfeckes zu der Summe der Fläche der Dreiecke, die ich horizontal schraffiert habe. - Und jetzt werde ich ein nach oben stehendes Fünfeck zeichnen, welches dadurch entsteht, daß ich es umschreibe dem Pentagramm. Nun müssen Sie nicht die Dreiecke nehmen, die da gleichsam wie Zipfel entstehen, sondern das gesamte Fünfeck, eingeschlossen die Fläche des Pentagrammes, also alles, was ich vertikal schraffiere. Also dieses vertikal schraffierte, dem Pentagramm umschriebene Fünfeck bitte ich zu berücksichtigen. So wie sich verhält der Flächeninhalt, die Größe dieses kleinen Fünfeckes hier, das mit der Spitze nach unten gerichtet ist, zu der Fläche dieses vertikal schraffierten Fünfeckes, das mit der Spitze nach oben gerichtet ist, so verhalten sich die Kräfte des physischen Leibes in ihrer Stärke zu den Kräften des Astralleibes im Menschen. Und so wie sich die horizontal schraffierten Dreiecke, wenn ich sie summiere, zu der Größe des Fünfeckes mit der Spitze nach oben verhalten, so verhält sich die Stärke der Kräfte des Ätherleibes zu der Stärke der Kräfte des Astralleibes. Kurzum, Sie haben in dieser Figur alles das angegeben, was man nennen kann: das gegenseitige Verhältnis der Kräfte des physischen Leibes, der Kräfte des Ätherleibes, der Kräfte des Astralleibes. Nur kommt das dem Menschen nicht alles zum Bewußtsein. Das mit der Spitze nach oben stehende Fünfeck umfaßt alles Astralische im Menschen, auch das, wovon der Mensch heute noch nichts weiß, was ausgearbeitet wird, indem das Ich den Astralleib immer mehr und mehr zum Geistselbst oder Manas umarbeitet.

Nun kann in Ihnen die Frage entstehen: Wie verhalten sich diese drei Hüllen zum eigentlichen Ich? Sie sehen, von dem eigentlichen Ich, von dem ich ausgesprochen habe, daß es das Baby ist, das am wenigsten entwickelte unter den menschlichen Wesensgliedern, von diesem Ich weiß der Mensch heute in der normalen Entwickelung noch sehr wenig. Die gesamten Kräfte dieses Ich liegen aber schon in ihm. Wenn Sie die Gesamtkräfte des Ich ins Auge fassen und ihr Verhältnis untersuchen wollen zu den Kräften des physischen Leiibes, Ätherleibes, Astralleibes, so brauchen Sie nur um die ganze Figur herum einen Kreis zu beschreiben. Ich will nun die Figur nicht zu sehr verschmieren. Wenn ich diesen Kreis noch schraffieren würde als ganze Fläche, so würde die Größe dieser Fläche im Vergleich zur Größe der Fläche des nach oben gerichteten Fünfeckes, im Vergleich zur Summe der Flächen der Dreieckzipfel, die horizontal schraffiert sind, im Vergleiche zu dem kleinen Fünfeck mit der Spitze nach unten, das ich ausgefüllt habe mit der Kreidesubstanz, das Verhältnis angeben der Kräfte des gesamten Ich repräsentiert durch die Fläche des Kreises - zu den Kräften des Astralleibes — repräsentiert durch die Fläche des großen Fünfeckes — zu den Kräften des Ätherleibes - repräsentiert durch die horizontal schraffierten Dreiecke, die sich ansetzen an das kleine Fünfeck - zu den Kräften des physischen Leibes - als zu der Fünfeckfläche, die mit der Kreidesubstanz ausgefüllt ist. Wenn Sie sich in der Meditation hingeben diesem okkulten Zeichen und sich innerlich ein gewisses Gefühl von dem Verhältnis dieser vier Flächen verschaffen, so bekommen Sie einen Eindruck von dem gegenseitigen Verhältnis von physischem Leib, Ätherleib, Astralleib und Ich. Sie müssen sich also denken in der gleichen Beleuchtung den großen Kreis und ihn in der Meditation ins Auge fassen. Dann stellen Sie daneben hin das aufwärtsstehende Fünfeck. Weil dieses Fünfeck etwas kleiner ist als der große Kreis, kleiner ist um diese Kreissegmente hier, wird Ihnen dieses aufwärtsstehende Fünfeck einen schwächeren Eindruck machen als der Kreis. Um was dieses schwächer ist als der Eindruck des Kreises, um das sind auch die Kräfte des Astralleibes schwächer als die Kräfte des Ich. Und wenn Sie sich als drittes hinstellen ohne das mittlere Fünfeck diese fünf Dreiecke, die horizontal schraffiert sind, so haben Sie wiederum einen schwächeren Eindruck, wenn Sie sich alles gleich beleuchtet denken. Um wieviel dieser Eindruck schwächer ist als der Eindruck von den beiden vorigen, um so viel schwächer sind die Kräfte des Ätherleibes als die Kräfte des Astralleibes und des Ich. Und wenn Sie sich das kleine Fünfeck hinstellen, so bekommen Sie bei gleicher Beleuchtung davon den schwächsten Eindruck. Wenn Sie nun sich ein Gefühl verschaffen von der gegenseitigen Stärke dieser Eindrükke und zusammenhalten können diese vier Eindrücke, wie Sie die Töne, sagen wir einer Melodie, in eines zusammendenken — wenn Sie diese vier Eindrücke in bezug auf ihre Größe zusammendenken, so haben Sie jene Stärkeharmonie, die besteht zwischen den Kräften des Ich, des Astralleibes, des Ätherleibes und des physischen Leibes. Das ist das, was ich Ihnen als ein okkultes Zeichen, gleichsam als ein Zeichen der okkulten Schrift hinstelle. Über solche Zeichen kann man meditieren.

Ich habe Ihnen ungefähr die Methode beschrieben, wie man das macht. Man verschafft sich den Eindruck der unterschiedlichen Stärken, die diese Flächen durch ihre Größenverhältnisse machen als gleichmäßig beleuchtete Flächen. Dann bekommt man eben einen Verhältniseindruck, der einem wiedergibt die gegenseitigen Maßverhältnisse der Kräfte der vier Glieder der menschlichen Wesenheit. Diese Dinge sind da als Zeichen der wirklichen, aus der Wesenheit der Dinge hervorgehenden okkulten Schrift. Meditieren diese Schrift heißt: lesen die großen Wunderzeichen der Welt, die uns hineinführen in die großen Geheimnisse der Welt. Dadurch verschaffen wir uns allmählich ein Gesamtverständnis von dem, was da draußen wirkt als Weltenwunder, die darin bestehen, daß der Geist in die Materie sich hineinergießt nach bestimmten Verhältnissen. Ich habe zugleich dadurch hervorgerufen in Ihnen etwas, was wirklich wie das Elementarste geübt wurde in der alten pythagoräischen Schule. Denn dadurch fängt der Mensch an, durch sein Geistgehör die Harmonien und Melodien der Kräfte in der Welt zu vernehmen, daß er von den Zeichen der okkulten Schrift ausgeht, sie realisiert und dann schon merkt, daß er die Welt mit ihren Wundern in ihrer Wahrheit geschaut hat. Davon werden wir dann morgen weitersprechen. Ich wollte heute als den Zielpunkt der Betrachtung dieses Zeichen der okkulten Schrift vor Ihre Seele hinstellen, das uns wiederum ein Stück hineingeführt hat in die Menschennatur.

Third Lecture