Posthumous Essays and Fragments

1879-1924

GA 46

23 September 1890

Translated by Ruth Hofrichter

18. Atomism and its Refutation

First, we will call to mind the current doctrine of sense impressions, then point to contradictions contained in it, and to a view of the world more compatible with the idealistic understanding.

Current (1890) natural science thinks of the world-space as filled with an infinitely thin substance called ether. This substance consists of infinitely small particles, the ether atoms. This ether does not merely exist where there are no bodies, but also in the pores (pertaining) to bodies. The physicist imagines that each body consists of an infinite number of immeasurable small parts, like atoms. They are not in contact with each other, but they are separated by small interstices. They, in the turn, unite to larger forms, the molecules, which still cannot be discerned by the eye. Only when an infinite number of molecules unite, we get what our senses perceived as bodies.

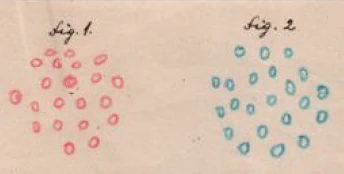

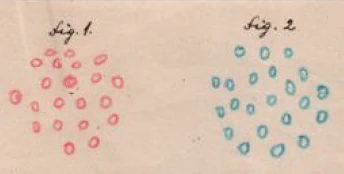

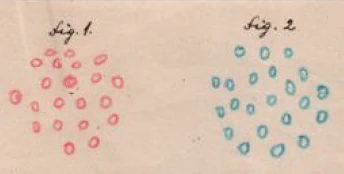

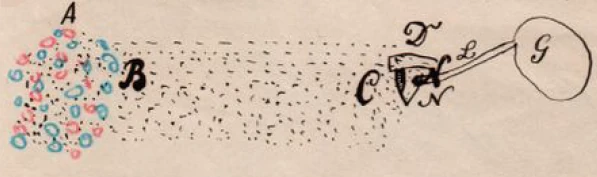

We will explain this by an example. There is a gas in nature, called hydrogen, and another called oxygen. Hydrogen consists of immeasurable small hydrogen atoms, oxygen of oxygen atoms. The hydrogen atoms are given here as red circlets, the oxygen ones as blue circlets. So, the physicist would imagine a certain quantity of hydrogen, like a figure 1, a quantity of oxygen like figure 2. (See table)

Now we are able, by special processes, not interesting us here, to bring the oxygen in such a relation to the hydrogen that two hydrogen atoms combine with one oxygen atom, so that a composite substance results which we would have to show as indicated in figure 3.

Here, always two hydrogen atoms, together with one oxygen atom form one whole. And this still invisible, small formation, consists of two kinds of atoms, we call a molecule. The substance whose molecule consists of two hydrogen atoms, plus one oxygen atom is water.

It also can happen that a molecule consists of 3, 4, 5 different atoms. So one molecule of alcohol consists of atoms of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen.

But we also see by this that for modern physics each substance (fluid, solid, and gaseous) consists of parts between which there exist empty spaces (pores).

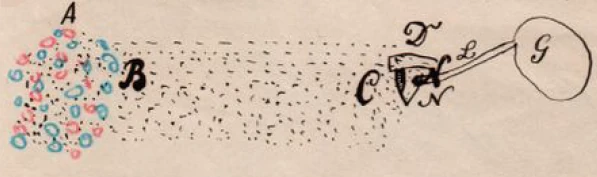

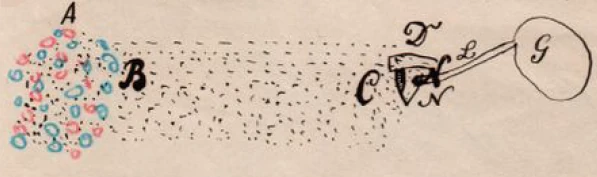

Into these pores, there enter the ether atoms which fill the whole cosmos. So, if we draw the ether atoms as dots, we have to imagine a body like figure 4. (The red and blue circlets are substance atoms, the black dots are ether atoms.)

Now we have to imagine that both the substance-atoms and the ether-atoms are in a state of constant motion. The motion is swinging. We must think that each atom is moving back and forth like the pendulum of a clock.

Now in A (see figure 5) we imagine a body, the molecules of which are in constant motion. This motion is transferred also to the ether-atoms in the pores, and from there, to the ether outside of the body of B, e.g. to C. Let us assume in D a sense-organ e.g. the eye, then, the vibrations of the ether will reach the eye, and through it, the nerve N. There, they hit, and through the nerve-conduit L, they arrive at the brain G. Let us assume for instance that the body A is in such a motion that the molecule swings back and forth 461 billion times a second. Then, each ether-molecule also swings 461 billion times, and hits 461 billion times against the optic nerve (in H). The nerve-conduit L transfers these 461 billion vibrations to the brain, and here, we have a sensation: in this case high red. If there were 760 billion vibrations I could see violet, at 548 billion yellow, etc. To each color sensation there corresponds, in the outside world, a certain motion.

This is even simpler in the case of the sensations of sound. Here also the body-molecules vibrate. The medium transferring this to our ear is not the ether but the air. At 148 vibrations per second we perceive the tone D, at 371 the tone F sharp, etc.

Thus we see to what this whole interpretation leads: whatever we perceive in the world with our senses, colors, tones, etc., is said not to exist in reality, but only to appear in our brain when certain vibratory forms of motion are present in the outer world. If I perceive heat, I do so only because the ether around me is in motion, and because the ether atoms hit against the nerves of my skin; when I sense light, it is because the same ether atoms reach the nerve of my eye, etc.

Therefore, the modern physicist says: in reality, nothing exists except swinging, moving atoms; everything else is merely a creation of my brain, formed by it when it is touched by the movement in the outer world.

I do not have to paint how dismal such a view of the world is. Who would not be filled with the saddest ideas if for example, Hugo Magnus, who is quite caught in that way of thinking, exclaims, “This motion of the ether is the only thing which really and objectively exists of color in creation. Only in the human body, in the brain, these ether movements are transformed into images which we usually call red, green, yellow, etc. According to this, we must say: creation is absolutely colorless ... Only when these (colorless) ether movements are led to the brain by the eye, they are transformed to images which we call color.” (Hugo Magnus, Farben und Schöpfung, 8 lectures about the relation of color to man and to nature, Breslau, 1881, p. 16f.)

I am convinced that everyone whose thinking is based on sound ideas, and who has not been subjected from early youth to these strange jumpy thoughts, will consider this state of affairs as simply absurd.

This matter, however, has a much more dubious angle. If there is nothing in the real world except swinging atoms, then there cannot be any true objective ideas and ideals. For when I conceive an idea, I can ask myself, what does it mean outside of my consciousness?—Nothing more than a movement of my brain molecules. Because my brain molecules at that moment swing one way or another, my brain gives me the illusion of some idea. All reality in the world then is considered as movement, everything else is empty fog, result of some movement.

If this way of thinking were correct, then I would have to tell myself: man is nothing more than a mass of swinging molecules. That is the only thing in him that has reality. If I have a great idea and pursue it to its origin, I will find some kind of movement. Let us say I plan a good deed. I only can do that if a mass of molecules in my brain feels like executing a certain movement. In such a case, is there still any value in “good” or “evil”? I can't do anything except what results from the movement of my brain molecules.

From these causes came the pessimism of delle Grazie. She says: For what purpose is this illusionary world of ideas and ideals when they are nothing but movements of atoms. And she believes that current science is right. Because she could not transcend science, and could not, as apathetic people do, disregard the misery of this belief; she succumbed to pessimism.

(See Rudolf Steiner and Marie delle Grazie, Nature and Our Ideals, published by Mercury Press.)

The error underlying the theories of this science is so simple that one cannot understand how the scientific world of today could have succumbed to it.

We can clarify the issue by a simple example. Let us suppose someone sends me a telegram from the place A. When it reaches me, I get nothing but paper and lettering. But if I know how to read, I receive more than merely paper and printed signs, that is, a certain content of thought. Can I say now: I have created this content of thought only in my brain, and paper plus lettering are the only reality? Certainly not. For the content which is now in me is also present in the place A in the same manner. This is the best example one can choose. For in a visible way, nothing at all has come to me from A. Who could maintain that the telegraph wires carry the thought from one place to the other? The same is true about our sense impressions. If a series of ether particles, swinging 589 billion times a second, reach my eye and stimulate the optic nerve, it is true that I have the sensation green. But the ether waves as paper and written symbols for the telegram in the example above are only the carriers of “green”, which is real on the body. The mediator is not the reality of the matter.

As wire and electricity for the telegram, so the swinging ether is here used as mediator. But just because we apprehend “green” by means of the swinging ether, we cannot say: “green” is simply the same as the swinging ether.

This coarse mistaking of the mediator for the content that is carried to us, lies at the root of all current sciences.

We must assume “green” as a quality of bodies. This “green” causes a vibration of 589 billion vibrations per second, this vibration comes to the optic nerve which is so constructed that it knows: when 589 billion vibrations arrive, they can only come from a green surface.

The same holds true for all other mental representations. If I have a thought, an idea, an ideal, it of course must be present in my brain as a reality. That is only possible if the brain particles move in a certain way, for an entity existing in space cannot suffer any changes except by motions. But we would be deadly mistaken about the content of the idea as compared to the way it appears in the body, if we were to say: the motion itself is the idea. No—the motion only provides the possibility for the idea to gain form and spatial existence.

But there is another aspect. For us men, there is nothing [in] which we are completely present as in our ideas, our ideals and mental representations. For them we live, we weave.

When we are alone in the dark, in complete silence, so that we have no sense impressions,—of what are we totally and fully conscious?—Our thoughts and ideas! After these comes everything we can experience through the senses. That is given to me when I open my sense organs to the outer world and keep them receptive. Aside from ideas, ideals and sense impressions, nothing is given to me. Everything else can only be derived as existing and ideas on the basis of our sense impressions.

Can I make such an assumption about moving atoms? If motion occurs, there must be something that moves. By what do I recognize motion? Only by seeing that the bodies change their place in space. But what I see before me are bodies with all qualities of color, etc.

So what does the physicist want to explain? Let us say color. He says: it is motion. What moves? A colorless body. Or, he wants to explain warmth. He again says: it is motion. What moves? A body without warmth. In short: if we explain all qualities of bodies by motion, we finally have to assume that the moving objects have no qualities, as all qualities originate in motion.

To recapitulate. The physicist explains all sense-perceivable, all sense-perceptible qualities by motion. So, what moves cannot yet have qualities. But what has no qualities cannot move at all. Therefore, the atom assumed by physicists is a thing that dissolves into nothing if judged sharply.

So, the whole way of explanation falls. We must ascribe to color, warmth, sounds, etc., the same reality as to motion. With this, we have refuted the physicists, and have proved the objective reality of the world of phenomena and of ideas.

18. Die Atomistik und ihre Widerlegung.

Wir wollen uns zuerst die heute allgemein übliche Lehre von der Sinnesempfindung vergegenwärtigen und dann auf die Widersprüche in derselben und auf eine der idealistischen Weltansicht gemäßere Anschauung hinweisen.

Die heutige Naturwissenschaft denkt sich den ganzen Weltraum mit einem unendlichen dünnen Stoffe, dem Äther, ausgefüllt. Dieser Stoff besteht aus lauter unendlich kleinen Teilen, den Ätheratomen. Dieser Äther ist nicht nur da vorhanden, wo keine Körper sind, sondern auch in den Poren, die sich in den Körpern befinden. Der Physiker stellt sich nämlich vor, dass ein jeder Körper aus unendlich vielen, unmessbar kleinen Teilen, den Atomen, besteht. Diese Atome sind nicht unmittelbar aneinanderliegend, sondern durch kleine Zwischenräume voneinander getrennt. Die Atome vereinigen sich wieder zu größeren Gebilden, den Molekülen, die aber noch immer für das bloße Auge nicht wahrnehmbar sind. Erst indem sich unendlich viele Moleküle aneinandergruppieren, entsteht das, was wir mit den Sinnen als Körper wahrnehmen.

Wir wollen diese Vorstellungsweise an einem Beispiele erläutern. Es gibt in der Natur ein Gas, das wir Wasserstoff, und ein solches, das wir Sauerstoff nennen. Der Wasserstoff besteht nun aus unmessbar kleinen Wasserstoffatomen, der Sauerstoff aus ebensolchen Sauerstoffatomen. Wir wollen die Wasserstoffatome mit roten, die Sauerstoffatome mit blauen Kreischen bezeichnen. Sonach würde sich der Physiker ein bestimmtes Quantum Wasserstoff wie unsere Fig. 1, ein solches von Sauerstoff wie Fig. 2 vorstellen.

Wir sind nun imstande, den Wasserstoff durch besondere Vorgänge, die uns hier nicht weiter interessieren, zum Sauerstoffe in eine solche Beziehung zu setzen, dass sich an je ein Wasserstoffatom ein Sauerstoffatom anlagert, sodass dann ein zusammengesetzter Stoff entsteht, den wir durch folgende Fig. 3 darstellen müssten:

Hier bilden immer je ein Wasserstoffatom mit einem Sauerstoffatom ein Ganzes. Und dieses aus zwei Atomen bestehende, noch immer nicht wahrnehmbare kleine Gebilde nennen wir Molekül. Der Stoff aber, dessen Moleküle aus je einem Wasserstoff- und einem Sauerstoffatom besteht, ist das Wasser.

Es kann auch sein, dass ein Molekül aus 3, 4, 5 etc. verschiedenen Atomen besteht. So besteht ein Molekül Weingeist (Spiritus) aus Atomen von Kohlenstoff, Wasserstoff und Sauerstoff.

Zugleich sehen wir aber hieraus, dass sich die moderne Physik jeden Körper (flüssige, feste und gasförmige) aus Teilen bestehend vorstellt, zwischen denen leere Raumteile (Poren) sind.

In diese Poren dringen nun die Ätheratome, die den ganzen Weltraum ausfüllen, auch ein, sodass wir uns, wenn wir die Ätheratome als Punkte (mit [schwarzer] Tinte) einzeichnen, einen Körper wie Fig. 4 vorzustellen haben.

Nun muss man sich vorstellen, dass sowohl die Körper- wie die Ätheratome in fortwährendem Zustande der Bewegung sind. Diese Bewegung ist eine schwingende. Man muss sich denken, dass ein jedes (sowohl Körperwie Äther-) Atom sich so hin- und herbewegt wie das Pendel einer Uhr.

Nun stellen wir uns bei A einen Körper vor, dessen Moleküle in unaufhörlicher Bewegung sind. Diese Bewegung überträgt sich auf die Ätheratome in den Poren und von da auf den Äther außerhalb des Körpers von B, zum Beispiel bis C. Nehmen wir nun an: in D sei ein Sinnesorgan, z.B. das Auge, so werden die Schwingungen des Äthers an das Auge und durch dasselbe hindurch an den Nerv N kommen, dort anschlagen und von da durch die Nervenleitung L bis in das Gehirn G geleitet werden.

Nehmen wir z.B. an: der Körper A sei in einer solchen Bewegung, dass das Molekül in einer Sekunde 461 billionenmal hin- und herschwingt. Dann schwingt auch jedes Äthermolekül 461 billionenmal hin und her und stößt 461 billionenmal an den Sehnerv (in N), die Nervenleitung Z. überträgt diese 461 Billionen Schwingungen bis zum Gehirn, und hier haben wir eine Empfindung, in diesem Falle: hochrot. Der Physiker sagt also: Während ich mir hochrot vorstelle, geschieht in der Außenwelt nichts weiter, als dass die Moleküle 461 Billionen Schwingungen in einer Sekunde ausführen. Wenn sie statt 461 Billionen Schwingungen 760 Billionen hätten, dann würde ich violett, bei 548 Billionen gelb usw. empfinden. Jeder Farbenempfindung entspricht in der Außenwelt eine bestimmte Bewegung.

Einfacher ist dies noch bei der Schallempfindung. Hier schwingen auch die Körpermoleküle. Das Mittel aber, welches diese Schwingungen an unser Ohr überträgt, ist nicht der Äther, sondern die Luft. Wenn z.B. die Moleküle eines Körpers 148 Schwingungen ausführen und die Luft diese 148 Schwingungen bis zu unserem Ohre fortpflanzt, so nehmen wir den Ton [d] wahr, bei 371 fis’ usw.

Wir sehen also, worauf diese ganze Lehre hinauswill. Alles, was wir in der Welt mit den Sinnen wahrnehmen: Farben, Töne usw. soll nicht wirklich existieren, sondern nur in unserem Gehirne auftreten, wenn in der Außenwelt bestimmte schwingende Bewegungsformen vorhanden sind. Wenn ich Hitze wahrnehme, so ist dies nur deshalb, weil der Äther um mich herum in Bewegung ist und die Ätheratome an meine Hautnerven anschlagen; wenn ich Licht empfinde, weil dieselben Ätheratome an meinen Sehnerven herankommen usw.

Daher sagt der moderne Physiker: Es gibt in Wirklichkeit nichts als schwingende, sich bewegende Atomg; alles Übrige ist nur ein Geschöpf meines Gehirnes, das sich dieses bildet, wenn es von der Bewegung in der Außenwelt berührt wird.

Ich brauche nicht auf das Trostlose einer solchen Weltansicht hinzuweisen. Wer möchte nicht von den traurigsten Vorstellungen erfüllt werden, wenn z.B. Hugo Magnus, der ganz in dieser Richtung befangen ist, ausruft: «Die Ätherbewegung ist das Einzige, was von der Farbe wirklich und wahrhaftig objektiv vorhanden ist. Erst im menschlichen Körper, im Gehirn werden diese Ätherbewegungen zu den Vorstellungen umgeformt, welche wir für gewöhnlich als Rot, Gelb, Grün usw. bezeichnen. Wir müssen sonach also sagen, die Welt an sich ist absolut farblos; erst dadurch, dass die farblosen Ätherbewegungen durch das Auge unserm Gehirn zugeführt werden, werden sie zu Vorstellungen umgeschaffen, die wir Farbe nennen.» Ich bin überzeugt davon, dass jedermann, dessen Denken auf einer gesunden Ideengrundlage ruht und der nicht von Jugend an in diese sonderbaren Gedankensprünge eingewöhnt worden ist, die Sache einfach absurd finden muss.

Die Sache hat aber eine noch viel bedenklichere Seite. Wenn es in der wirklichen Welt überhaupt nichts gibt als schwingende Atome, dann kann es auch keine wahrhaft objektiven Ideen und Ideale geben. Denn wenn ich eine Idee fasse, so kann ich mich fragen: Was bedeutet diese Idee außer meinem Bewusstsein. Nichts weiter als eine Bewegung meiner Hirnmoleküle. Weil meine Hirnmoleküle in diesem Momente so und so schwingen, gaukelt mir mein Gehirn irgendeine Idee vor. Alles Wirkliche in der Welt wäre Bewegung, das andere leerer Dunst, Erzeugnis dieser Bewegung.

Wäre diese Vorstellungsweise die richtige, dann müsste ich mir sagen, der Mensch ist weiter nichts als eine Masse schwingender Moleküle. Dies ist das allein Wirkliche an ihm. Habe ich eine große Idee und verfolge sie nach ihrem Ursprunge, so komme ich auf diese oder jene Bewegung. Ich will eine gute Handlung vollbringen. Dies kann ich nur, wenn es gerade einer Masse von Molekülen meines Gehirnes beliebt, eine bestimmte Bewegung auszuführen. Hat unter solchen Voraussetzungen gut oder schlecht überhaupt noch einen Wert? Ich kann ja doch nur vollbringen, was aus der Bewegung meiner Gehirnmoleküle resultiert.

Aus diesen Beweggründen ist der Pessimismus der delle Grazie hervorgegangen. Sie sagt: Wozu diese Gaukelwelt von Ideen und Idealen, wenn dies nichts ist als Bewegung der Atome. Und sie glaubt an die Richtigkeit der heutigen Naturwissenschaft. Weil sie sich über diese nicht erheben kann und nicht wie die gleichgültigen Menschen über die Trostlosigkeit hinwegkommt, darum verfiel sie dem Pessimismus.

Der Fehler, der den Schlüssen dieser Naturwissenschaft zugrunde liegt, ist so einfach, dass man in der Tat nicht begreifen kann, wie die ganze gelehrte Welt der Gegenwart in diesen grenzenlosen Irrtum verfallen konnte.

Wir können durch ein einfaches Beispiel die Sache klarmachen. Nehmen wir einmal an, jemand gibt in dem Orte A ein Telegramm an mich auf. Wenn mir das Telegramm überbracht wird, habe ich nichts vor mir als Papier und Schriftzeichen. Indem ich diese Dinge mir aber gegenüberhalte und zu lesen verstehe, erfahre ich wesentlich mehr, als was Papier und Schriftzeichen sind, nämlich einen ganz bestimmten Gedankeninhalt. Kann ich nun sagen: ich habe diesen Gedankeninhalt erst in meinem Gehirne erzeugt, und das einzig Wirkliche seien nur Papier und Schriftzeichen? Gewiss nicht. Denn der Inhalt, den ich jetzt in mir habe, ist genau ebenso auch im Orte A enthalten. Dieses Beispiel ist sogar das treffendste, das man wählen kann. Denn es ist doch auf sichtbare Weise nicht das Allergeringste von A herüber zu mir gekommen. Wer wollte behaupten, dass die Telegrafendrähte wirklich die Gedanken von einem Orte zum andern tragen? Genau ebenso ist es mit unseren Sinnesempfindungen. Wenn eine Reihe von Ätherteilchen, die in einer Sekunde 589 billionenmal hin- und herschwingen, an mein Auge kommen und den Sehnerv erregen, so tritt bei mir allerdings z.B. die Empfindung des Grün auf. Aber die Ätherwellen sind, wie oben beim Telegramm, Papier und Schriftzeichen, nur die Träger des Grün, das an dem Körper wirklich ist. Der Vermittler ist ja doch nicht das Wirkliche der Sache. So wie beim Telegramm Draht und Elektrizität, so wird hier der schwingende Äther als Vermittler benützt. Man darf aber deshalb, weil wir durch und vermittelst des schwingenden Äthers das Grün erfassen, nicht sagen: Grün sei einfach dasselbe wie der schwingende Äther.

Diese grobe Verwechslung von Vermittler und Inhalt, der vermittelt wird, liegt der ganzen modernen Naturwissenschaft zugrunde.

Man muss annehmen, das Grün sei eine Eigenschaft der Körper; dieses Grün errege eine schwingende Bewegung von 589 Billionen Schwingungen in der Sekunde, diese Bewegung kommt an den Sehnerv und dieser sei so eingerichtet, dass er weiß, wenn 589 Billionen Schwingungen ankommen, dann können diese nur von einer grünen Fläche ausgegangen sein.

Ebenso ist es mit allen unsern andern Vorstellungen beschaffen. Wenn ich einen bestimmten Gedanken, Idee, Ideal habe, so muss derselbe natürlich auch auf reale Weise in unserem Gehirne gegenwärtig sein. Dies ist nur so möglich, dass die Gehirnteile in einer bestimmten Weise sich bewegen. Denn ein im Raume ausgedehntes Wesen kann keine anderen Veränderungen als Bewegungen erleiden. Aber es wäre eine arge Verwechslung von dem Inhalte der Idee und der Art, wie sie im Körper auftritt, wenn man sagen wollte: die Bewegung selbst sei die Idee. Nein, die Bewegung bietet nur die Möglichkeit, dass die Idee Gestalt, räumliches Dasein, gewinnt.

Wir können aber die Sache noch von einer ganz anderen Seite anfassen. Es gibt für uns Menschen überhaupt nichts, worinnen wir so ganz gegenwärtig sind, wie unsere Ideen, Ideale und Vorstellungsmassen. In ihnen leben und weben wir. Wenn wir im Dunkeln, in lautloser Stille sind, sodass wir gar keine Sinneseindrücke haben, was ist das, wessen wir uns da ganz und voll bewusst sind? Unsere Gedanken und Ideen. Nach diesen kommt dann alles, was ich durch die Sinne wahrnehme. Dieses habe ich gegeben, wenn ich meine Sinnesorgane der Außenwelt gegenüber offen und empfänglich halte. Außer Ideen, Idealen und Sinneseindrücken ist mir aber nichts gegeben. Alles Übrige könnte nur erschlossen, d.h. aufgrund der Sinneseindrücke und Ideen als bestehend angenommen werden.

Darf ich eine solche Annahme in Bezug auf bewegte Atome machen? Wenn Bewegung stattfindet, so muss doch etwas da sein, welches sich bewegt. Woher kenne ich die Bewegung? Doch nur daher, dass ich sehe, dass die Körper ihren Ort im Raume verändern. Was aber sich da vor mir bewegt, das sind Körper mit allen Eigenschaften von Farbe usw.

Was will also der Physiker erklären? Sagen wir die Farbe. Er sagt: sie sei Bewegung. Was bewegt sich? Ein farbloser Körper. Oder er will die Wärme erklären. Er sagt wieder, sie ist Bewegung usf. Was bewegt sich? Ein wärmeloser Körper. Kurz: Wenn wir alle Eigenschaften der Körper durch Bewegung erklären, so müssen wir zuletzt doch annehmen, dass jenes, was sich bewegt, keine Eigenschaften hat. Denn alle Eigenschaften entstehen ja erst aus der Bewegung.

Wir rekapitulieren: Der Physiker erklärt alle durch die Sinne wahrzunehmenden Eigenschaften durch Bewegung. Was sich bewegt, kann somit noch keine Eigenschaften haben. Was aber keine Eigenschaften hat, kann sich überhaupt nicht bewegen. Folglich ist das Atom, das die Physiker annehmen wollen, ein Ding, das vor der scharfen Beurteilung in Nichts zerfließt.

Die ganze Erklärungsweise zerfällt damit. Wir müssen den Farben sowie der Wärme, den Tönen usw. geradeso eine objektive Existenz zuschreiben wie der Bewegung. Damit haben wir die Physiker widerlegt und die objektive Realität der Erscheinungs- und Ideenwelt nachgewiesen.

Rudolf Steiner

18. Atomism and its Refutation

Let us first consider the generally accepted doctrine of sensory perception and then point out the contradictions in it and a view more in line with the idealistic worldview.

Modern science conceives of the entire universe as filled with an infinitely thin substance, ether. This substance consists of infinitely small particles, ether atoms. This ether is not only present where there are no bodies, but also in the pores that are found in bodies. Physicists imagine that every body consists of an infinite number of immeasurably small particles, called atoms. These atoms do not lie directly next to each other, but are separated by small spaces. The atoms combine again to form larger structures, called molecules, which are still invisible to the naked eye. Only when an infinite number of molecules group together does what we perceive with our senses as a body come into being.

Let us illustrate this concept with an example. In nature, there is a gas that we call hydrogen and another that we call oxygen. Hydrogen consists of immeasurably small hydrogen atoms, and oxygen consists of equally small oxygen atoms. Let us designate the hydrogen atoms with red circles and the oxygen atoms with blue circles. A physicist would then imagine a certain quantum of hydrogen as shown in Fig. 1 and a quantum of oxygen as shown in Fig. 2.

We are now able, through special processes that are not of interest to us here, to place hydrogen in such a relationship with oxygen that an oxygen atom attaches itself to each hydrogen atom, resulting in a composite substance that we would have to represent by the following Fig. 3:

Here, one hydrogen atom and one oxygen atom always form a whole. We call this small structure, consisting of two atoms and still imperceptible, a molecule. The substance whose molecules consist of one hydrogen atom and one oxygen atom is water.

It is also possible for a molecule to consist of 3, 4, 5, etc. different atoms. For example, a molecule of ethyl alcohol (spirit) consists of atoms of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen.

At the same time, however, we can see from this that modern physics imagines every body (liquid, solid, and gaseous) as consisting of parts between which there are empty spaces (pores).

The ether atoms, which fill the entire universe, also penetrate these pores, so that if we draw the ether atoms as dots (with [black] ink), we can imagine a body like the one in Fig. 4.

Now we must imagine that both the body atoms and the ether atoms are in a constant state of motion. This motion is a vibrating one. One must imagine that each atom (both physical and etheric) moves back and forth like the pendulum of a clock.

Now let us imagine a body at A whose molecules are in constant motion. This motion is transmitted to the ether atoms in the pores and from there to the ether outside the body of B, for example to C. Now let us assume that in D there is a sensory organ, e.g., the eye, then the vibrations of the ether will reach the eye and pass through it to the nerve N, strike there, and from there be conducted through the nerve pathway L to the brain G.

Let us assume, for example, that body A is in such motion that the molecule oscillates back and forth 461 trillion times in one second. Then every ether molecule also oscillates back and forth 461 trillion times and strikes the optic nerve (in N) 461 trillion times. The nerve conduction Z transmits these 461 trillion vibrations to the brain, and here we have a sensation, in this case: bright red. So the physicist says: While I imagine bright red, nothing else happens in the outside world except that the molecules perform 461 trillion vibrations in one second. If they had 760 trillion vibrations instead of 461 trillion, I would perceive violet, and at 548 trillion, yellow, and so on. Every color sensation corresponds to a specific movement in the outside world.

This is even simpler with sound perception. Here, too, the molecules of the body vibrate. However, the medium that transmits these vibrations to our ears is not ether, but air. For example, when the molecules of a body perform 148 vibrations and the air propagates these 148 vibrations to our ears, we perceive the sound [d], at 371 fis', etc.

So we see what this whole theory is getting at. Everything we perceive in the world with our senses: colors, sounds, etc., does not really exist, but only occurs in our brain when certain vibrating forms of movement are present in the outside world. When I perceive heat, it is only because the ether around me is in motion and the ether atoms strike my skin nerves; when I perceive light, it is because the same ether atoms strike my optic nerves, etc.

That is why modern physicists say: In reality, there is nothing but vibrating, moving atoms; everything else is just a creation of my brain, which forms it when it is touched by movement in the outside world.

I need not point out the bleakness of such a worldview. Who would not be filled with the saddest thoughts when, for example, Hugo Magnus, who is completely caught up in this line of thinking, exclaims: "The movement of the ether is the only thing that is truly and objectively present in color. Only in the human body, in the brain, are these ether movements transformed into the ideas we usually call red, yellow, green, etc. We must therefore say that the world itself is absolutely colorless; only when the colorless ether movements are fed to our brain through the eye are they transformed into ideas that we call color." I am convinced that anyone whose thinking is based on a sound foundation of ideas and who has not been accustomed to these strange leaps of thought since childhood must find the matter simply absurd.

But there is an even more worrying side to the matter. If there is nothing in the real world but vibrating atoms, then there can be no truly objective ideas and ideals. For when I conceive an idea, I can ask myself: What does this idea mean apart from my consciousness? Nothing more than a movement of my brain molecules. Because my brain molecules are vibrating in a certain way at this moment, my brain is deceiving me with some idea. Everything real in the world would be movement, the rest empty vapor, a product of this movement.

If this way of thinking were correct, then I would have to say to myself that humans are nothing more than a mass of vibrating molecules. This is the only thing that is real about them. If I have a great idea and trace it back to its origin, I arrive at this or that movement. I want to accomplish a good deed. I can only do this if a mass of molecules in my brain happens to perform a certain movement. Under such conditions, does good or evil even have any value? After all, I can only accomplish what results from the movement of my brain molecules.

These motives gave rise to delle Grazie's pessimism. She says: Why this illusory world of ideas and ideals, if it is nothing but the movement of atoms? And she believes in the correctness of today's natural science. Because she cannot rise above it and cannot overcome the desolation like indifferent people, she succumbed to pessimism.

The error underlying the conclusions of this natural science is so simple that it is indeed impossible to understand how the entire learned world of the present could have fallen into this boundless error.

We can clarify the matter with a simple example. Let us assume that someone sends me a telegram from location A. When the telegram is delivered to me, all I have in front of me is paper and letters. But by looking at these things and understanding how to read them, I learn much more than what paper and letters are, namely a very specific thought content. Can I now say that I first created this thought content in my brain, and that the only real things are paper and letters? Certainly not. For the content that I now have within me is also contained in location A. This example is actually the most apt one that can be chosen. For visibly, not the slightest thing has come over to me from A. Who would claim that telegraph wires really carry thoughts from one place to another? It is exactly the same with our sensory perceptions. When a series of ether particles, oscillating 589 trillion times per second, reach my eye and stimulate the optic nerve, I do indeed experience, for example, the sensation of green. But the ether waves, like the paper and characters in the telegram above, are only the carriers of the green that is real in the body. The mediator is not the reality of the matter. Just as the telegram uses wire and electricity, here the vibrating ether is used as a mediator. However, just because we perceive green through and by means of the vibrating ether, we cannot say that green is simply the same as the vibrating ether.

This gross confusion between the mediator and the content being mediated underlies the whole of modern science.

One must assume that green is a property of bodies; this green excites a vibrating motion of 589 trillion vibrations per second, this motion reaches the optic nerve, and this nerve is designed in such a way that it knows that when 589 trillion vibrations arrive, they can only have originated from a green surface.

The same applies to all our other ideas. If I have a certain thought, idea, or ideal, then it must of course also be present in our brain in a real way. This is only possible if the parts of the brain move in a certain way. For a being that extends in space cannot undergo any changes other than movements. But it would be a serious confusion of the content of the idea and the way it appears in the body to say that the movement itself is the idea. No, the movement only offers the possibility for the idea to take shape, to gain spatial existence.

But we can approach the matter from a completely different angle. For us humans, there is nothing in which we are as fully present as our ideas, ideals, and imaginations. We live and breathe in them. When we are in darkness, in silent stillness, so that we have no sensory impressions at all, what is it that we are fully and completely aware of? Our thoughts and ideas. After these come everything that I perceive through my senses. I have this when I keep my sensory organs open and receptive to the outside world. But apart from ideas, ideals, and sensory impressions, nothing else is given to me. Everything else can only be inferred, i.e., assumed to exist on the basis of sensory impressions and ideas.

May I make such an assumption with regard to moving atoms? If movement takes place, there must be something there that moves. How do I know about the movement? Only because I see that the bodies change their location in space. But what moves in front of me are bodies with all the properties of color, etc.

So what does the physicist want to explain? Let's say color. He says it is movement. What is moving? A colorless body. Or he wants to explain heat. Again, he says it is movement, and so on. What is moving? A heatless body. In short, if we explain all the properties of bodies through movement, we must ultimately assume that that which moves has no properties. For all properties arise only from movement.

Let's recap: The physicist explains all properties that can be perceived by the senses through movement. What moves cannot therefore have any properties. But what has no properties cannot move at all. Consequently, the atom that physicists want to assume is a thing that dissolves into nothingness when subjected to sharp judgment.

The entire explanation thus falls apart. We must attribute an objective existence to colors, heat, sounds, etc., just as we do to motion. We have thus refuted the physicists and proven the objective reality of the world of appearances and ideas.